TEGUCIGALPA— In another dramatic swing of the political pendulum, Honduras’s new President Nasry Asfura began his term promising austerity and small-government efficiency. In his inaugural address on January 27, he offered a marked contrast to the leftist government of his predecessor Xiomara Castro, vowing to shrink the public sector and declaring that “decentralization is essential for effective governance.”

Asfura, the conservative former mayor of Tegucigalpa (2014-22), plans sizeable cuts to the national budget, but has also pledged to improve health care, education, and infrastructure. To do so, the 67-year-old former businessman is likely to lean on public-private partnerships as part of a broader effort to attract private investment. He has also pledged a “head-on” program to fight crime and improve investment conditions, as well as broad incentives for the private sector: One of his first actions was the extension of the Temporary Import Regime, a fiscal exemption framework that benefits capital-intensive export sectors and firms reliant on imported inputs, such as the maquila and shrimp industries.

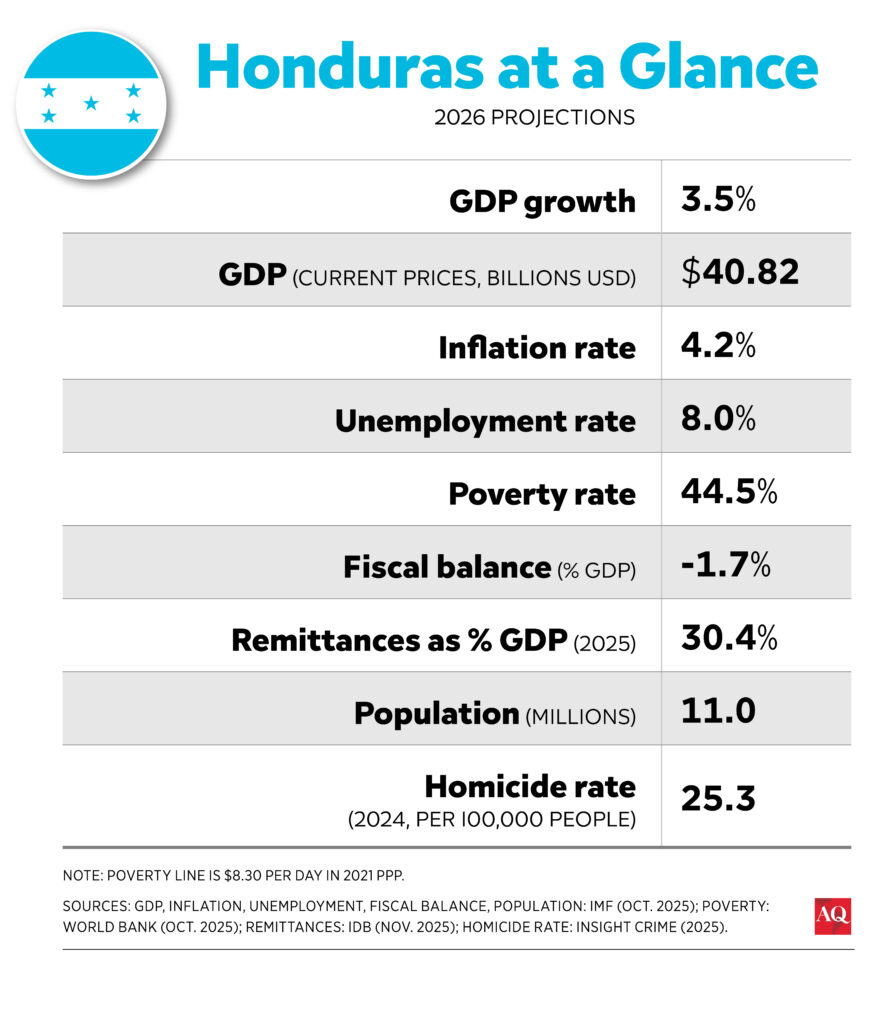

Asfura, whose term ends in 2030, has some wind in his sails. He inherits an economy projected to grow 3.5% this year and poverty rates that, though high, fell modestly under Castro. His National Party also controls the largest bloc in the legislature, with 49 of 128 seats, and is likely to be able to build durable working majorities.

But Honduras faces serious challenges, including a public health system on the verge of collapse; falling but still unacceptably high homicide rates; deteriorating, sub-par roads and other infrastructure; and fragile governability threatened by corruption and organized crime. It is also beset by intense polarization and public mistrust of institutions made worse by the November election that brought Asfura to office. His victory was narrow and contested, and the country’s elections authority, weakened by partisanship and institutional decay, delayed vote counts and did little to assuage public perceptions of fraud. Institutional weakness, lack of state capacity, and lack of popular buy-in are likely to hinder Asfura’s agenda.

A struggle for legitimacy

Asfura’s most immediate challenge is to mitigate the ongoing crisis in the public health sector: thousands of patients are languishing on surgery waiting lists, and shortages of medicines and supplies are becoming acute. His administration has already declared a public health emergency, which allows the state to more quickly contract supplies and services from the private and nonprofit sectors, widely viewed as the beginning of a broader push that is expected to replace a range of public services with private ones.

These quick actions show responsiveness from the administration, but belie deeper problems. Asfura’s inauguration, held inside the National Congress and limited to roughly 200 attendees, took place under a cloud of heavy security. Multiple rings of soldiers and police restricted access to downtown Tegucigalpa, creating the image of a president sworn in behind barricades rather than welcomed by an expectant public.

Authorities justified the scene based on the jarring incident of January 8: an improvised explosive device was thrown at a National Party lawmaker, detonating and seriously injuring her. The public interpreted this as an attack by Libre Party supporters on the incoming National Party government. Despite the gravity of the attack, the police have yet to offer any explanation or transparency into their investigation.

This has reinforced long-standing concerns about impunity and institutional weakness. Honduras is classified by the Bertelsmann Transformation Index as a “highly defective democracy,” with limited economic transformation and only moderate governance performance. While the country moved away from the open authoritarian drift of the late 2010s and achieved a peaceful transfer of power in 2021, progress has been shallow. State capacity remains weak, accountability mechanisms fragile, and public trust low.

A fragile democracy

Asfura’s predecessor came to power in 2022 promising a leftist “refoundation” of the nation. Over time, Castro’s administration concentrated control over all three branches of government and became embroiled in corruption scandals and allegations of ties to drug traffickers. Her administration also drew criticism for using a prolonged state of emergency to combat crime. Though homicides declined, it was widely criticized for undermining civil liberties, and did little to reduce extortion and other serious crimes.

Despite all this, campaign season offered little substantive discourse. There were no presidential debates and no sustained discussion of economic or social policy. Instead, aggressive culture-war rhetoric dominated, as evangelical and Catholic leaders inveighed against “gender ideology” and cast the left as a threat to traditional values.

U.S. influence also played a key role. In the campaign’s final stretch, as the National Party’s lobbying efforts intensified in Washington, President Donald Trump endorsed Asfura. This energized Asfura’s base, helped consolidate the National Party’s vote, and reframed the race in geopolitical terms; support from the U.S. is key for Honduras, given its large migrant population and its dependence on remittances, which in 2025 totaled the equivalent of 30% of the country’s GDP. Just before the election, Trump also pardoned former President Juan Orlando Hernández (2014-22), of Asfura’s National Party, stirring controversy.

Hernández had consolidated power, leaned on the Supreme Court to overturn a constitutional ban on reelection, and strongarmed his way to a second term, undermining other democratic mechanisms along the way. After leaving office, he was extradited to the U.S. and sentenced in 2024 to 45 years in prison on drug-trafficking charges before securing a pardon.

With Asfura at the helm, a plurality of voters opted to give the National Party another chance. For his part, Asfura has promised progress without partisanship. In an encouraging sign, some of his Cabinet members have technocratic rather than political profiles. For example, Roberto Lagos, who was appointed to the Central Bank, is an economist trained at U.S. institutions, such as the University of North Carolina and Duke University, and is better known as an independent economist than a National Party loyalist.

Whether his administration can deliver stable governance, however, will depend less on legislative majorities or international backing than on a willingness to confront the institutional roots of Honduras’ recurring crises. The November election laid bare the consequences of having a politicized rather than technocratic elections authority, and similar problems extend throughout Honduras’s government.

Without deep institutional reform, instability will beat out democratic consolidation, and this new start will likely fall into the same old patterns: The pendulum will continue to swing, fragile initiatives will crack up, and uncertainty will only deepen.