TEGUCIGALPA — More than two dozen Honduran drug traffickers, politicians and businessmen have passed through U.S. courts since 2012, when the two countries signed an extradition agreement. The most important defendant, former President Juan Orlando Hernández (2014-22), was convicted of drug and weapons trafficking on March 8. He is awaiting sentencing and faces a minimum of 40 years in U.S. prison, where his brother, a former congressman, is himself serving a life sentence for drug trafficking.

But in Honduras, these convictions are seen as just a drop of justice in a desert of impunity. President Xiomara Castro vowed to crack down on graft and reestablish an international anti-corruption commission when she assumed the presidency in 2022, but progress has been slow. Reform has been snarled in a political system still dominated by old-guard parties, and investigations are disproportionately targeting the opposition. The fate of the potential UN commission seems ever more uncertain, and anti-corruption efforts as a whole may be at risk of unraveling.

Castro was elected as a leftist change candidate on the heels of Hernández’s two controversial terms in office. Hernández had come to power in the aftermath of a 2009 coup d’état that deposed Castro’s husband, Manuel Zelaya, who was marched at gunpoint to an airport and flown out of the country. The government then organized elections with U.S. backing that ushered in 12 years of right-wing National Party rule, marked by election scandals and increasing political violence, corruption and drug trafficking.

During his tenure, Hernández packed the courts, which then overturned the nation’s ban on presidential reelection. Hernández ran again in 2017, and won in a vote marred by international observers’ claims of fraud—though the U.S. supported the results. In 2020, Hernández shut down the MACCIH anti-corruption commission backed by the Organization of American States (OAS), which had opened several hard-hitting investigations. He cooperated extensively with the U.S. by extraditing drug traffickers, but during his trial U.S. prosecutors successfully argued he was simply eliminating the competition.

U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland said Hernández “abused his position as President of Honduras to operate the country as a narco-state where violent drug traffickers were allowed to operate with virtual impunity.” For his part, Hernández testified on the stand that in Honduras, drug traffickers “support everyone … or at least they try.”

Honduras has long struggled with corruption even compared with its peers in the Americas, ranking ahead of only Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela in Transparency International’s 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index. It is a key reason why Honduras is “one of the poorest and most unequal countries in the region” according to the World Bank, as well as one of the top three countries of origin for migrants attempting to enter the U.S. since 2020.

A new chapter?

Castro’s administration began promisingly, inking a deal with the UN to create the Commission Against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (CICIH), and giving law enforcement better tools to investigate money laundering. But it hasn’t finalized basic details for the CICIH, like its scope, that could determine its success or failure. Nor has it pushed the fundamental legal reforms that may be necessary for the commission to succeed.

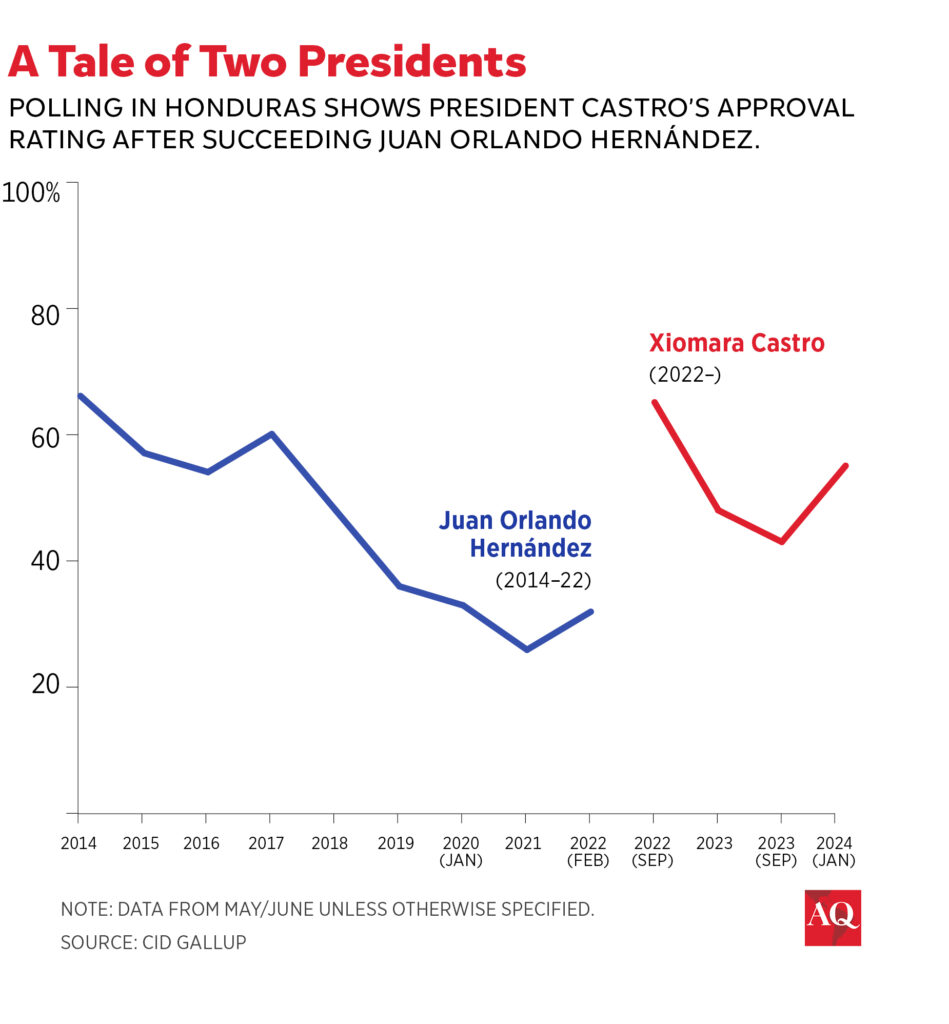

Ahead of elections in 2025, Castro is more focused on street-level crime, which partly explains her approval rating of around 55%. Her administration declared a controversial state of emergency that has lasted for over a year, deploying the military to the streets. Critics say it has had only limited success due to a lack of fundamental reform in policing and that it serves simply to grab headlines and chase votes. Similarly, if the UN commission is dropped into the snarl of what U.S. prosecutors dubbed a “narco-state” without domestic reform, it may flounder—or be shut down like the MACCIH or the CICIG in Guatemala before it. The warning signs abound.

The first is widespread nepotism. The National Anticorruption Council, a local NGO, denounced extensive family connections in government, even beyond the numerous positions of power held by Castro’s immediate family: Castro’s eldest child is her private secretary, her youngest daughter is in Congress, her brother-in-law is the president of Congress, and his son is the defense minister.

During Hernández’s trial, a drug trafficking boss testified he had bribed this brother-in-law, Carlos Zelaya, to the tune of $100,000-200,000. (Zelaya denies wrongdoing.) Castro and her allies in the legislature also passed an amnesty law that ostensibly sought to protect those persecuted by past administrations, but critics say that in practice it shields some of her closest allies from prosecution.

Traditional party politics endure

Moreover, the hope surrounding the selection of a new Supreme Court and attorney general has largely evaporated. All 15 Supreme Court seats were selected last year, and the traditional parties divided them between themselves. Castro’s LIBRE party had six of their nominations approved, while the National Party landed five and the Liberal Party landed four.

The Attorney General’s Office was similarly carved up; Congress failed to reach an agreement after months of wrangling, so Castro’s LIBRE party established a commission that pushed through its own “interim attorney general.” The National Party and the Liberal Party each also scored high-level positions in the office.

All told, these institutions may be more independent from the whims of any one party, but not the traditional party system itself. An OAS official recently said that even Honduras’ Clean Politics Unit, a government agency that is supposed to monitor political party campaigns, lacks the required tools.

The Hernández verdict shows how much still has to be done. For now, the Honduran political system seems to have blunted momentum for meaningful reform. Over the coming months, progress on the UN commission—or lack thereof—will measure domestic political will for change. Meanwhile, the actions of the new Supreme Court, the Attorney General’s Office and the Clean Politics Unit—as well as the parties’ electioneering—will provide clues as to whether such a commission could survive at all.

—

Ávila is a Honduran journalist and the director of the outlet Contracorriente.