The creation of Haiti’s nine-member Transitional Presidential Council (TPC) seemed in itself a victory. It is a fragile but critical alliance that, taking on the role of the president of this Caribbean nation, is tasked with appointing a prime minister and forming a government over the coming months. It will seek to stabilize the country in time for elections scheduled for February 2026.

But in its initial tasks of naming its own leader and the prime minister, it failed to put aside internal tensions, raising doubts about its ability to deliver on any of its aims and get this violence-stricken country back on track. On April 30, four of its seven voting members chose Fritz Bélizaire to replace the interim prime minister, Michel Patrick Boisvert, without consulting the rest of the council—let alone holding a formal vote—on the grounds that it had a majority. A little-known official, Bélizaire served as Haiti’s sports minister during the second presidency of René Préval from 2006 to 2011.

The outcry from the other TPC members, civil society, and the international community led the four members to backtrack. If they actually do, and a new, less contentious vote is held, the TPC may be able to recover from this false start.

The TPC was convened through many months of intense behind-the-scenes negotiating between various powerbrokers. Since its inception, it has been widely panned for involving old-guard politicians and parties by a range of observers, from academics to lawyers to gang leaders. A principal concern was that the politicians would treat this special body as they might any other position of power, with little desire for compromise and using government resources and positions to advance their own interests, give allies jobs and shield themselves from accountability. The TPC’s immediate false start only reinforced these concerns and seemed to vindicate the council’s critics.

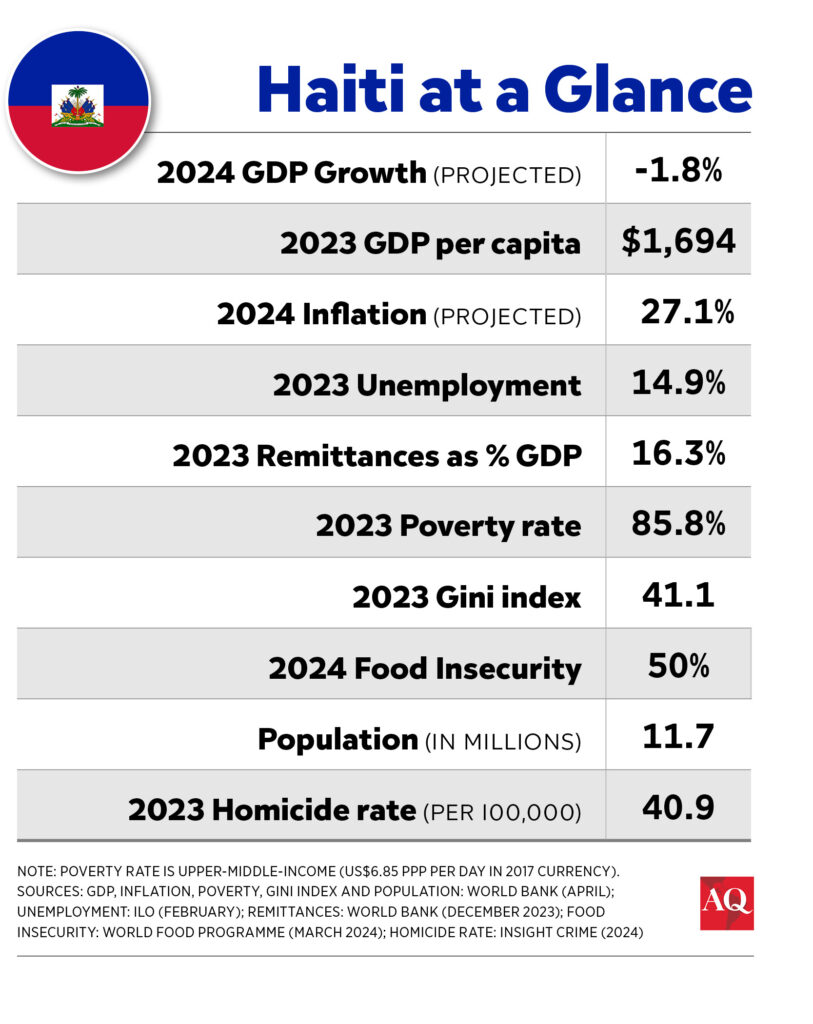

It’s easy, therefore, to understand why most Haitians doubt a TPC-led transitional government can quell the most recent crisis that started on February 29 as armed gangs launched coordinated attacks in various parts of the country. The events led to the resignation of prime minister Ariel Henry and this new era of special government as Haiti seeks to leave behind violent conflicts in which 2,500 people have been injured or killed this year alone.

False start

After the TPC’s first misstep, all the pressure that Caricom and the rest of the international community used to seat the council in the first place must now be directed toward ensuring the council uses transparent, orderly processes to appoint a new prime minister and the heads of the other ministries in a way that inspires confidence.

If the TPC continues to fail to do this, it will either fall apart or limp along much as it already has. Instead of communicating directly with each other, its members have been releasing attacks on ONE ANOTHER other through the press. Some have also skipped meetings; three members didn’t attend a May 2 meeting with Caricom.

But if it succeeds in this first step, it may stand a chance of organizing elections. After all, in 2015, Interim President Jocelerme Privert managed to do so in an unstable security environment without foreign support after the international community refused to fund another election.

At this stage, there are no guarantees. Even the UN-approved Kenyan security force cannot be viewed as a silver bullet to restore a semblance of order. It is a relatively small force that still lacks a solid plan, a concrete roadmap, and sustained funding. It is by no means a given that this force will be able to defy Haiti’s history of failed security interventions.

The international community can do more to set up the UN mission and the TPC for success. It would require a great deal of technical and financial support to local police, but also clear mechanisms for accountability to prevent and punish graft or underperformance. Likewise, various ministries will need the same kind of support to address the unfolding humanitarian crisis, but in a way that encourages sustainability instead of dependency.

Zero-sum game

As for the gangs, they are looking for amnesty and consideration. They want to be considered legitimate actors and treated as powerful ones. Governments, political factions and economic power-players in Haiti have a long tradition of negotiating with and using gangs for security, crowd control, and the intimidation of rivals. The gangs are now actively trying to reestablish these kinds of ties with the best-connected political actors.

The TPC has inherited the population’s unaddressed needs and the previous government’s untouched agenda. The outgoing government failed to deliver after 30 months in power despite political support from the international community because it lacked political will and a clear roadmap.

Now, the 2026 elections serve as a clear, concrete goal. But the specter of a contested, chaotic vote looms large over the process. The quality and credibility of the elections will depend on the quality and credibility of the steps taken to organize them. The task is daunting; encouraging the public to participate on election day will be especially challenging, considering that the voter turnout in the last elections held in 2016 was less than 20%, and that internal displacement and mass migration will further complicate the mobilization of voters. And at the first hint of fraud or interference, the elections will be contested, which could trigger new political crises.

Haitian politics is often a zero-sum game, and politicians and their foreign allies usually fail to rise to the occasion. There have been some positive signs of collaboration among council members and the groups they represent. They have come together in defiance of the outgoing government’s attempts to undermine them and the gangs’ threats to attack them. The council will need to proceed in a spirit of relative unity and complete transparency. Legitimate debate should exist—it seems already to have acted as an effective check on an initial overstep and proved that the council can still avoid mortal pitfalls. Either way, the future of the nation is in their hands.