This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on trends to watch in Latin America in 2025.

Guyana continues to surprise. When we published our broad overview of the nation a year ago, its economy was expected to grow 21% in 2024. However, as total crude output exceeded expectations, the nation’s gross domestic product most likely rose 44% last year, according to most recent projections from the IMF. With the start of its oil boom in 2019, Guyana’s remarkable sequence of 19 years of uninterrupted expansion took on new proportions.

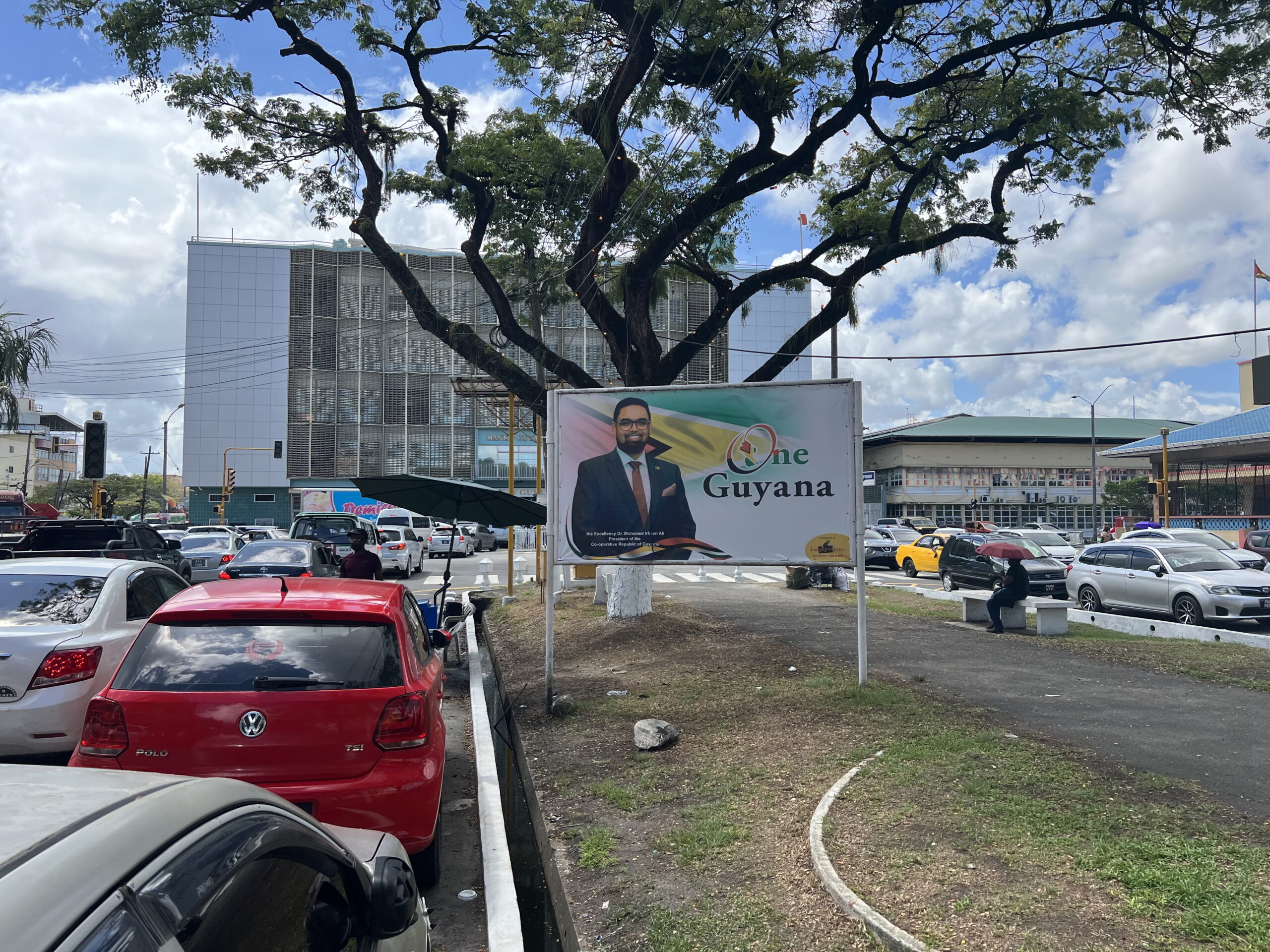

Once one of the poorest countries in the Western Hemisphere, Guyana is cementing its status as a rising regional star. Using proceeds from its oil wealth, President Irfaan Ali announced in October a one-off cash transfer of $1,000 for every household and reinstated free college tuition. Completing the large-scale fiscal stimulus, the government promised to raise the monthly minimum wage from $350 to $500 starting in 2025 and cut onerous electricity bills by half. According to the government, the measures seek to tackle the rising cost of living, but one fact is inescapable: Guyana holds general elections in November, and Ali’s People’s Progressive Party/Civic (PPP/C) is trying not only to get him reelected, but also grow its majority in parliament beyond its precarious current hold on 33 of 65 seats.

The announcement marks another signal of a petrostate in the making as a series of infrastructure projects, including new roads, bridges, and hospitals, continue to advance mainly in the capital and its surroundings. “There’s a mad flurry of activity driven by the government and the private sector,” Thomas Singh, professor of economics and director of the University of Guyana’s Green Institute, recently told AQ. The massive fiscal expansion anchored in a record-high $5.5 billion budget is causing the economy to overheat, Singh said, and “we are pushing ourselves beyond full employment, relying on migrants” to fill a significant number of jobs in sectors such as construction and services.

The 2024 budget represented a 47% nominal increase compared to the $3.75 billion approved for 2023. The Finance Ministry will unveil the 2025 budget in January, and analysts expect another sizable boost in government spending as November’s elections are on the horizon. Local media have reported that the government is set to withdraw $2.3 billion in oil revenue from its Natural Resource Fund (NRF) in 2025 to fund the budget. This would represent a 46% increase from the almost $1.6 billion approved for use this year.

Silica City, an entirely new “smart city” in the tropical savanna and one of the government’s signature projects, is advancing slowly. While 110 houses in phase one are being built, a master plan presented by the University of Miami is still under review by the Housing Ministry. The renovation and construction of several hospitals in Georgetown and the provinces are also underway. At the same time, long car lines are now even more pronounced when crossing the capital’s Demerara River as the work on a new bridge—being built by a Chinese consortium and partially financed by the Bank of China—is still in progress. Reflecting the need for urgent modernization, Guyana approved for 2024 disbursements of $976 million for roads and bridges and $350 million for community roadworks, almost 20% of last year’s budget.

With all this, after an expected GDP expansion of 44% in 2024, the IMF sees Guyana’s economy growing a more “modest” 14% this year, taking the total economic output to almost $25 billion, compared to $4.8 billion in 2018 before the oil boom started.

Other relevant matters remain pending or undecided. While the president appointed a constitutional reform commission last April to revise the nation’s main charter and electoral system, its members have yet to issue recommendations. At the same time, civil society leaders have been pushing for a referendum to renegotiate the nation’s production-sharing agreement with the ExxonMobil-led consortium before the elections. Still, whether the three main political parties will agree to organize the plebiscite is unclear. A recent poll by the Georgetown-based law firm Ram and McRae showed that 94% of those consulted favor setting new terms for developing the nation’s vast oil reserves. Under the current accord, Guyana receives 2% of oil production as royalties, and after the producing companies deduct their operational expenses and recovery costs, they split the profit 50/50 with the government.

A thriving oil sector

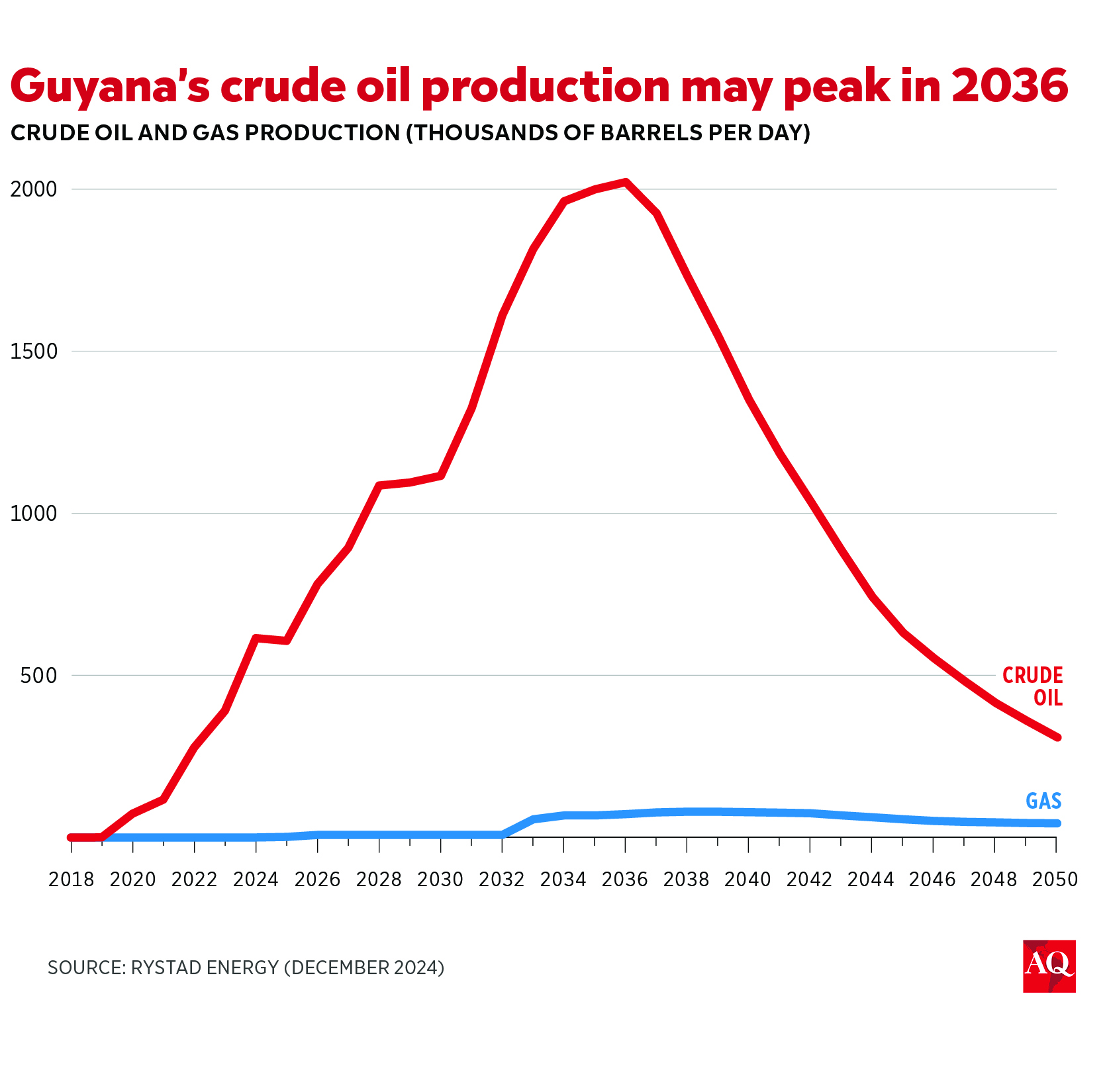

The oil sector continues adding production capacity. Last April, ExxonMobil, the leading company of the consortium producing offshore oil, announced a $12.7 billion project to add 250,000 barrels per day (bpd) of production capacity by the end of 2027. The nation’s total capacity will likely surpass 1.4 billion bpd by 2030 from the current 665,000 bpd, according to the projections of the Natural Resources Ministry. During this period, “government stability will be paramount,” Schreiner Parker, a managing director for Latin America at Rystad Energy, told AQ.

Guyana’s oil exports rose 54% in 2024 to 582,000 bpd, with much of that amount directed to European markets. The performance has catapulted the country to become the fifth-largest Latin American crude exporter after Brazil, Mexico, Venezuela and Colombia, according to data compiled by Reuters.

While oil production and exports are rising, the country’s vast gas resources are still untapped. A plan to develop a $30 billion export project is on the drawing board six months after the government commissioned it in June to Fulcrum LNG, a little-known U.S. startup founded in 2023 by a former Exxon executive. The bidding process raised some concerns because Fulcrum won the contract over 16 seemingly more qualified bidders.

Investors and allies

As the nation navigates its oil expansion and continues tackling its infrastructure limitations, Guyana is successfully engaging with international investors. In late November, India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, made a historic visit to Georgetown to sign energy and defense agreements. Modi signaled that the South American nation will be crucial to its energy security and said he plans to encourage Indian businesses to invest in the country. India is interested in buying oil from Guyana, but the details of that aspiration are still unclear.

Canada’s top commercial and development companies also visited in November to explore investment opportunities. Others, like Elon Musk’s Starlink, want to apply for a license to offer satellite internet service in the country.

Still, with its effervescent economic activity and the possibility of becoming the most strategic ally for the U.S. in the Americas, the government has yet to roll out a national development plan, One Guyana Developing Strategy, originally planned for last January. Instead, Ali’s administration relies on the PPP/C’s manifesto and the nation’s Low-Carbon Development Strategy 2030 to guide economic growth. But those two documents “can hardly be a development plan for any country,” Professor Singh told me. With elections just months away, “there is great pressure to complete projects, some of them almost overnight, like everything else nowadays in Guyana.”