GUATEMALA CITY — U.S. President Donald Trump is already eliciting loud responses throughout the hemisphere. Mexico has promised retaliation to new U.S. tariffs, and Panama has pushed back on Trump’s threats to seize the Panama Canal. Colombian and Brazilian officials have condemned the treatment of deportees flown to their countries. Honduran President Xiomara Castro has threatened to close a military base in response to mass deportations. In contrast, one country with arguably just as much at stake—Guatemala—has remained largely silent.

Over the last four years, the U.S. has deported more Guatemalans than any other group, and since Trump took office, multiple U.S. military planes carrying deportees have already landed in Guatemala City. As the Trump administration undertakes what it touts as the largest deportation effort in recent U.S. history, Guatemala’s President Bernardo Arévalo has been careful to avoid confrontation. Instead, the Arévalo administration seems committed to discreet diplomacy and pragmatic engagement.

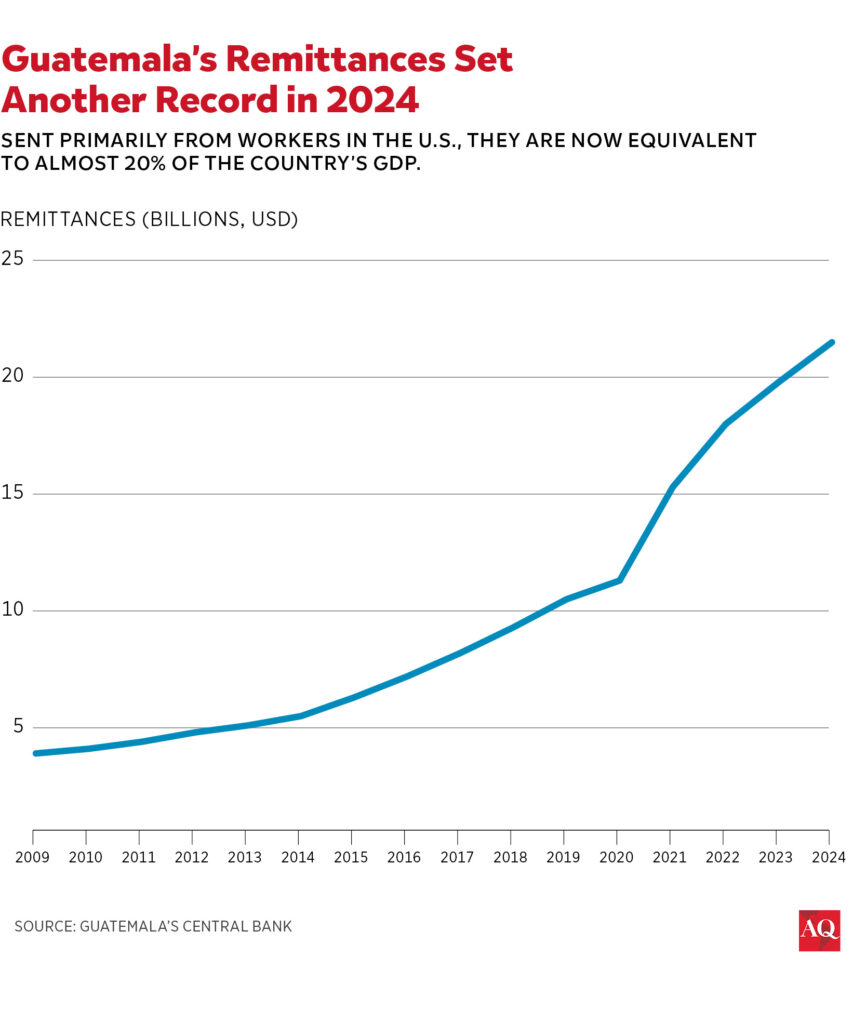

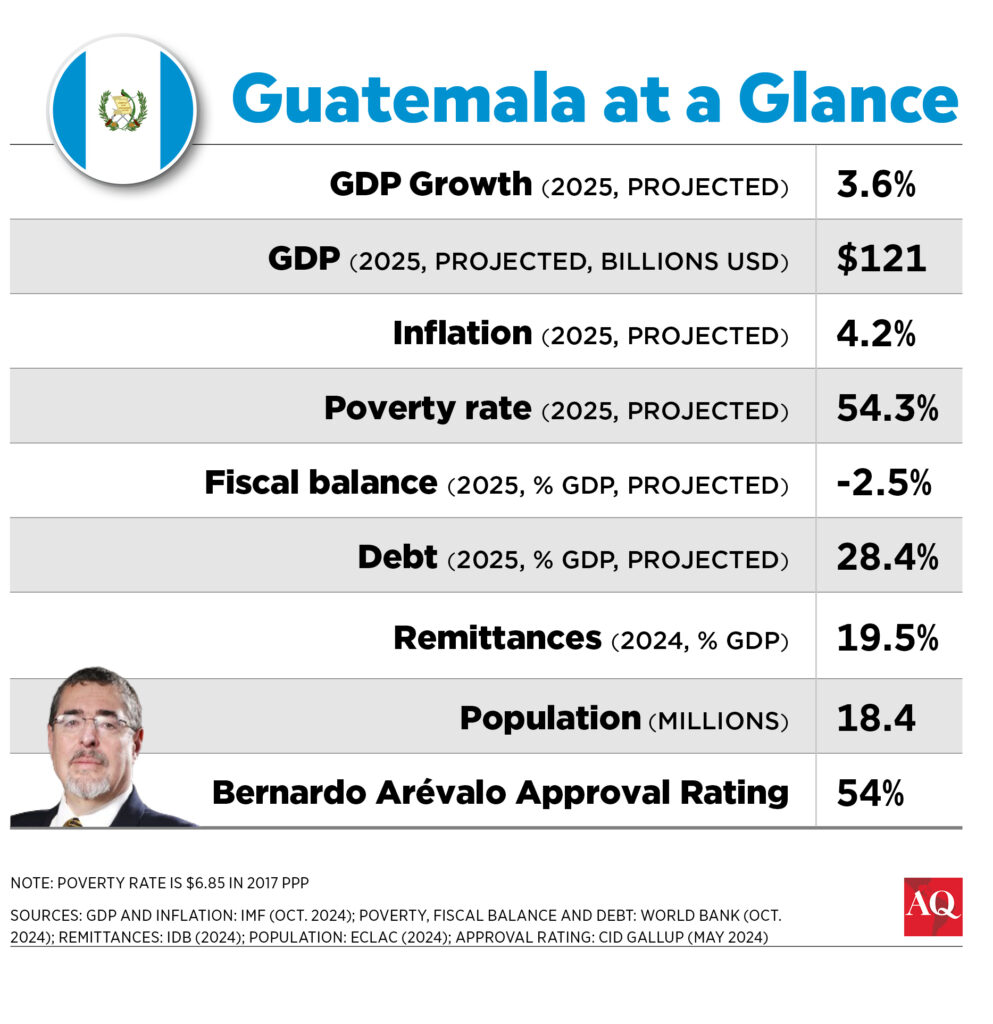

Guatemala’s relationship with the U.S. is vital. Last year, Guatemala received a record $21.5 billion in remittances—representing almost 20% of its GDP—mainly from workers in the U.S. Increased deportations and potential U.S. plans to tax remittances could significantly impact the country’s economy. These remittances dwarf both U.S. investment—about $250 million in 2024, according to Guatemala’s central bank—and bilateral trade. In 2023, U.S. exports to Guatemala, mostly fuel, machinery, and cereals, amounted to $9.7 billion, while it imported just $4.8 billion worth of goods.

Even so, Guatemala has been signaling that it’s willing to cooperate with the new White House. Unlike Honduras, it has maintained its extradition agreement with the U.S., it’s supporting Ukraine in its war against Russia, and it is one of just a handful of countries that maintain diplomatic relations with Taiwan over China. Arévalo also recently hosted Venezuelan opposition leader Edmundo González after condemning Nicolás Maduro’s rigged election and said that during his first year in office, Guatemala seized over twice the amount of drugs as it did in 2023, highlighting his commitment to fighting drug trafficking in Central America’s largest country.

Marco Rubio is traveling to Guatemala this week as part of his first overseas trip as Trump’s Secretary of State, reflecting the close ties between the two countries. The visit will test the Arévalo administration’s hopes of leveraging cooperation with the U.S. into greater investment and support for its government transparency efforts. Neither is a given, and both may be critical for Arévalo’s success. During Rubio’s visit, Arévalo will try to reinforce the message that his administration is “one of the few reliable U.S. partners” in Central America, as he put it in a recent interview, and that there is ample room for collaboration.

Strategy on deportations

The Arevalo government’s response to the prospect of mass deportations reflects its broader strategy. Instead of condemning the deportations, Arévalo has announced a plan to support deportees. The administration is expanding consular services in the U.S. and Mexico, establishing temporary shelters in Guatemala City, and undertaking a skill-certification program to offer recognition for the trades and language skills they have practiced in the U.S. The hope is that by conducting thorough interviews with deportees and logging their skills and experience, they can be more efficiently incorporated into Guatemala’s economy in sectors from construction to tourism.

But Guatemala’s economy will still struggle to accommodate them, Paul Boteo, an economics professor at Francisco Marroquin University in the nation’s capital, told AQ. The country creates only around 86,000 formal jobs a year, compared to around 260,000 young people who enter the workforce, and “that’s one of the main reasons people migrate to the U.S. in the first place,” Boteo said.

Trump administration ties

Though the Arévalo government has racked up a handful of significant wins during its first year in office, its progress is fragile; it faces a compromised court system, a fractured Congress, and a hostile Attorney General, Consuelo Porras, who has herself been sanctioned by the U.S. and over 40 other countries for allegedly undermining democracy and stonewalling corruption investigations.

Now, there is concern within the Arévalo government that the new Trump administration may undermine its transparency efforts and support Porras and her allies, some of whom have publicly celebrated Trump’s victory. The head of the Florida Republican Party, Bill Helmich, invited Porras to Trump inauguration events in Washington, though she could not attend as she is barred by U.S. sanctions from entering the country. Two other Public Ministry officials attended instead. Arévalo, meanwhile, was not invited. His administration will watch closely whether Rubio meets with Porras or other PM representatives.

In 2023, after Arévalo won that year’s presidential election, Porras and her allies attempted to prevent the president-elect and his party from taking office. This sparked massive demonstrations and pushback from the Joe Biden administration, which sanctioned almost 300 lawmakers and other powerbrokers. Arévalo eventually took office, but during the tumultuous transition, Richard Grenell, a former diplomat and intelligence official in the first Trump administration, visited Guatemala. He offered vocal support for conservative organizations suing to block Arévalo from taking office, as well as for Porras’ Public Ministry after it seized ballot boxes and criticized the Biden administration’s pressure. Grenell, who was a contender for the Secretary of State, is now an envoy for “special missions” in the second Trump administration.

For his part, Rubio supported Arévalo during the transition. However, as a senator in 2019, Rubio backed former Guatemalan President Jimmy Morales’ controversial move to shut down the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala, known as CICIG for its acronym in Spanish. Established in 2006 and funded by the UN and the U.S., the anti-corruption commission was widely popular in Guatemala. It had successfully prosecuted a raft of groundbreaking corruption cases, and had opened investigations into President Morales himself. Even so, the first Trump administration sided with Morales, who had painted CICIG as left-wing and curried favor with Trump by moving the Guatemalan embassy in Israel to Jerusalem in 2018.

Shortly thereafter, Morales and Trump signed a “safe third country” agreement, allowing the U.S. to send asylum seekers to Guatemala. Biden nixed this agreement, and Arévalo has said that while he’s opposed to any new “third-country” deal, he’s optimistic that there are other ways to cooperate.

The CICIG’s ouster was a major setback for transparency in the country long beset by endemic corruption. As Arévalo’s left-leaning administration attempts to rebuild the rule of law, he is eager to avoid antagonizing the Trump administration. Under his leadership, Guatemala will likely maintain a posture of broad acquiescence in search of a quiet coexistence with Washington.