BUENOS AIRES — The recent 90-day pause on most planned U.S. tariffs aside, President Donald Trump’s “reciprocal” strategy represents the most significant shift toward protectionism in U.S. trade policy in decades. These policies, which have shocked global markets for several sessions, may seem familiar to observers of Latin America’s recent economic history and deserve close attention. The region followed a similar approach from the 1940s-70s with import substitution industrialization (ISI), pursuing economic development through deliberate policies designed to foster domestic production and reduce dependence on foreign manufactured goods.

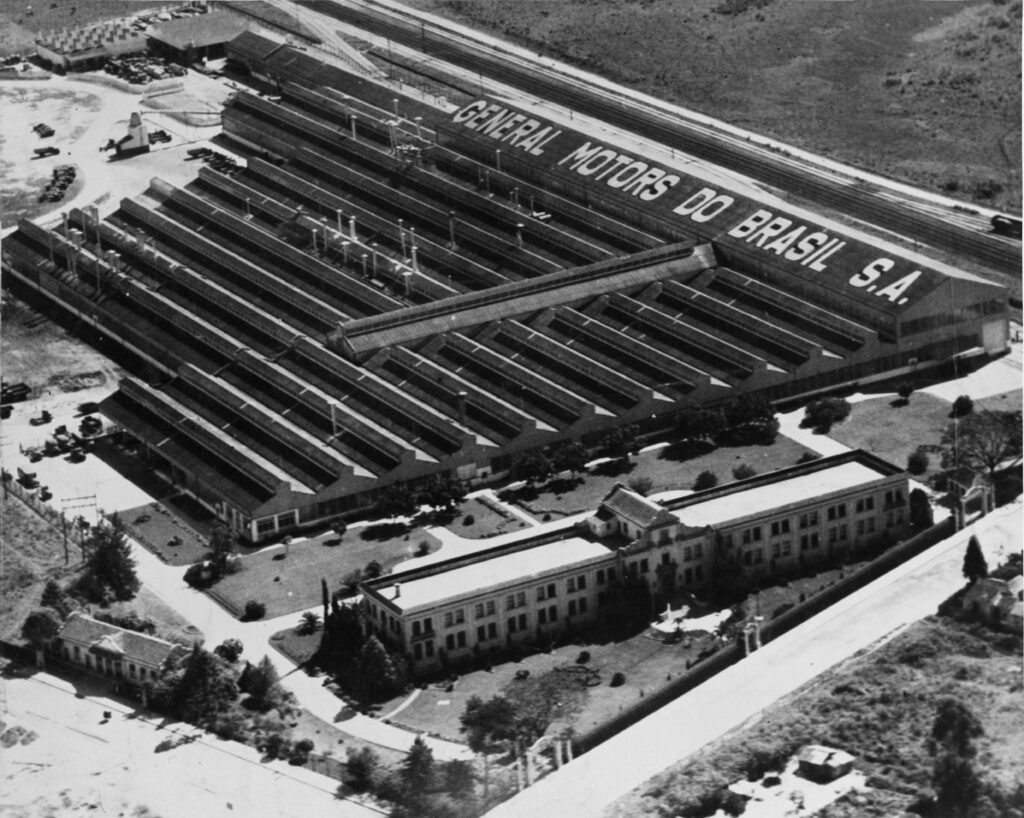

From Perón’s Argentina (where wage hikes and nationalizations backfired into inflation) to Brazil under Kubitschek (whose state-led production led to aggravated inflation) and Mexico’s monopolistic “Miracle” (epitomized by Telmex in communications, Pemex in oil, and CFE in electricity), ISI policies shared fatal flaws: All collapsed under inefficiency and cronyism when protections became permanent.

ISI across Latin America shared common features: protection of infant industries through high tariffs; exchange rate policies that often resulted in overvalued currencies—cheapening capital imports but undermining export competitiveness and external stability; direct state involvement in production; and preferential treatment for domestic manufacturers. The goal was ambitious: to transform predominantly agricultural economies into industrial powerhouses through government intervention.

For a time, ISI delivered impressive results. Manufacturing’s share of GDP rose markedly across the region. New industrial sectors emerged, employing millions and fueling the growth of an urban middle class. Yet despite these achievements, Latin America never fully converged with advanced economies. By the 1980s, most ISI regimes had buckled under mounting inefficiencies and unsustainable debt levels, culminating in the region’s “lost decade” of economic crisis. The U.S. would do well to heed Latin America’s protectionist missteps.

Latin America’s protectionist playbook

Among the many theories explaining ISI’s shortcomings, two criticisms stand out as particularly relevant when comparing Latin America’s experience with current U.S. trade policy.

First, Latin American industrialization lacked export orientation. In contrast to East Asian countries that combined protection with aggressive export promotion, Latin American firms focused almost exclusively on domestic markets. This inward orientation meant that protected industries remained small and inefficient, unable to achieve economies of scale or face the discipline of international competition.

Second, the implementation of ISI revealed significant gaps in state capabilities, particularly in effectively managing the private sector. As governments gained discretionary power to determine which industries received protection and subsidies, businesses shifted focus from improving productivity to lobbying for favorable treatment. The state’s inability to withdraw support from underperforming firms meant that inefficient companies thrived through political connections rather than economic merit—creating a class of business leaders who mastered the art of political lobbying while their factories remained decades behind global standards.

(Photo by R. Gates/Archive Photos/Getty Images)

Unlike Latin America’s ISI failures, East Asian economies conditioned protection on export performance, R&D investment, and eventual global competitiveness—precisely the path the U.S. seems to be ignoring.

New protectionism, old risks

Trump’s tariff strategy has several stated objectives: rebalancing global demand (forcing surplus countries to stimulate consumption), countering the U.S. dollar overvaluation (by improved terms of trade or geopolitical leverage), and even raising internal tax revenue (tariffs are a suboptimal tax).

Perhaps the main stated objective underlying the tariffs is to prevent technological downgrading attributed to the process of U.S. deindustrialization. The argument, not unlike the rationale behind ISI, suggests that certain economic activities—particularly those involving advanced manufacturing—generate positive spillovers that the private sector doesn’t fully capture. Under this logic, trade protection is needed to preserve key sectors—and the industrial jobs tied to them.

Given what we know from Latin America’s experience, does this approach make sense?

In Trump’s favor, one of ISI’s major weaknesses—limited market size—doesn’t apply to the U.S. With its massive consumer base, U.S. companies can potentially achieve economies of scale even without access to foreign markets. This addresses one critical limitation that hampered Latin American industrialization.

However, Trump’s approach lacks strategic focus. Tariffs have been raised indiscriminately across the board, treating advanced semiconductor production and plastic toy manufacturing with equal policy importance—a blunt-force approach that defies economic logic. For the rest of the economy, blanket protection simply raises prices and erodes competitiveness with no clear benefit. Particularly concerning is the rise in intermediate input costs, which makes U.S. production more expensive. In some cases, protection can backfire spectacularly when tariffs on inputs exceed those on final goods—creating what trade economists would call “negative effective protection,” where trade costs make it more expensive to produce domestically than to import. This was a common pattern in Latin America, where protected manufacturers often paid more for inputs than their foreign competitors.

The risk of cronyism

Beyond these immediate economic effects, there’s a significant risk that Trump’s trade protection will spark the same rent-seeking dynamics that plagued Latin America’s ISI regimes. These broad-based tariffs are unlikely to hold: Countless exceptions are likely to emerge by country and product (the recent exemptions to the tariff wall on China point in that direction).

U.S. companies may soon redirect resources toward lobbying activities, seeking to convince government officials that importing specific inputs from specific countries is crucial to avoid costly production disruptions. Business focus may shift from productivity enhancement to political influence, and corruption may likely follow.

This was one of the most salient lessons from Latin America’s ISI experience: Once local businesses start growing under the shade of protection, removing that protection becomes not just politically difficult but nearly impossible. In Argentina, entire industries became permanent wards of the state—inefficient, technologically backward, and politically untouchable. The temporary becomes permanent, turning economic policy from a development tool into a hold-up mechanism for politically connected firms.

The need for policy coherence

Even if tariffs could effectively help the U.S. maintain its position as a technological leader, they are unlikely to achieve this goal if implemented in isolation. Promoting vibrant basic and applied research at universities and technology institutes and facilitating companies’ innovation efforts is at least as important as protecting existing industries from foreign competition.

In this context, cuts to university funding and research institutions could easily undermine any potential benefits from trade protection. The most successful industrial policies—whether in postwar Japan and South Korea or modern China—combine selective protection with substantial investment in education, research, and innovation.

Moreover, protectionism may address inequality (e.g., manufacturing jobs for non-college workers), but without export incentives, these gains could be undone by retaliatory tariffs targeting U.S. farmers and exporters.

If the goal were really to preserve the U.S. industrial base and technological edge, a more disciplined and conditional design should at least include targeted protection (limiting tariffs to sectors with measurable spillovers); sunset clauses (automatic phase-out after a predetermined period); export orientation and required investment in education and R&D infrastructure; and mechanisms to prevent regulatory capture and rent-seeking behavior—all policies hard to implement in practice.

Crucially, even with all these elements—and setting aside the broader global and domestic costs of the tariff shock—it’s far from clear that protectionism would deliver its intended outcomes. Without them, the risks of repeating Latin America’s costly experience—with entrenched inefficiency, rising prices, and political capture—become all but certain. In that case, the promised industrial renaissance could produce politically connected oligarchs instead of globally competitive industries.