QUITO — This May could prove one of the most consequential months in Ecuador’s recent political history, as the possibility of an early change in government unfolds. After an impeachment motion was moved forward in Congress, President Guillermo Lasso threatened to call a muerte cruzada (roughly, “mutually assured destruction”)—the never-before-used presidential power to dissolve Congress, move up general elections and govern alone for six months. Meanwhile, the political climate in Ecuador is challenging, as both the president and the National Assembly have low approval ratings (17% and 20%, respectively).

Judging by the calendar set in motion by the constitutional court, the impeachment vote is set to happen by the middle of the month. First, a report by a Congressional committee is expected in the next few days, and a vote by the full chamber should happen by the second week of May. This process started on March 4, when the National Assembly approved a recommendation to impeach Lasso after journalistic exposés alleged corruption in public companies managed by some of the president’s trusted officials. Lasso has denied the allegations but on March 29, Ecuador’s Constitutional Court accepted a request to start the impeachment proceeding.

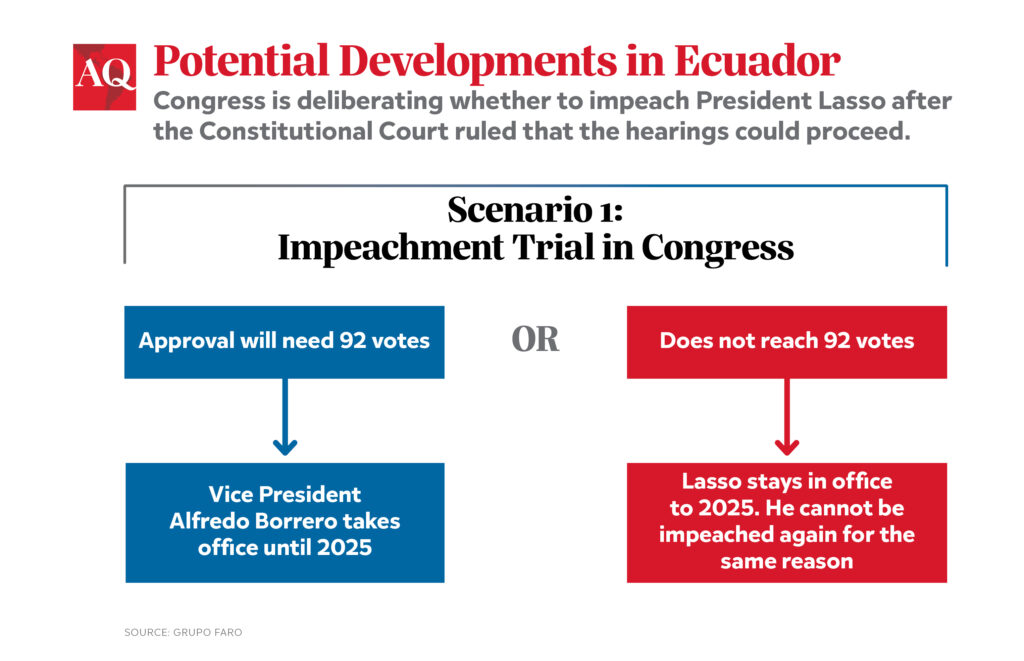

The impeachment has to be presented for a vote at a plenary session by May 23 and needs 92 votes, a supermajority, to pass. If Guillermo Lasso is impeached, Vice President Alfredo Borrero, a medical doctor and politician, will assume the position of head of state until the end of Lasso’s term, which runs until 2025. If the vote fails, a new impeachment cannot be proposed for the same reason and Guillermo Lasso would remain in office.

Muerte cruzada

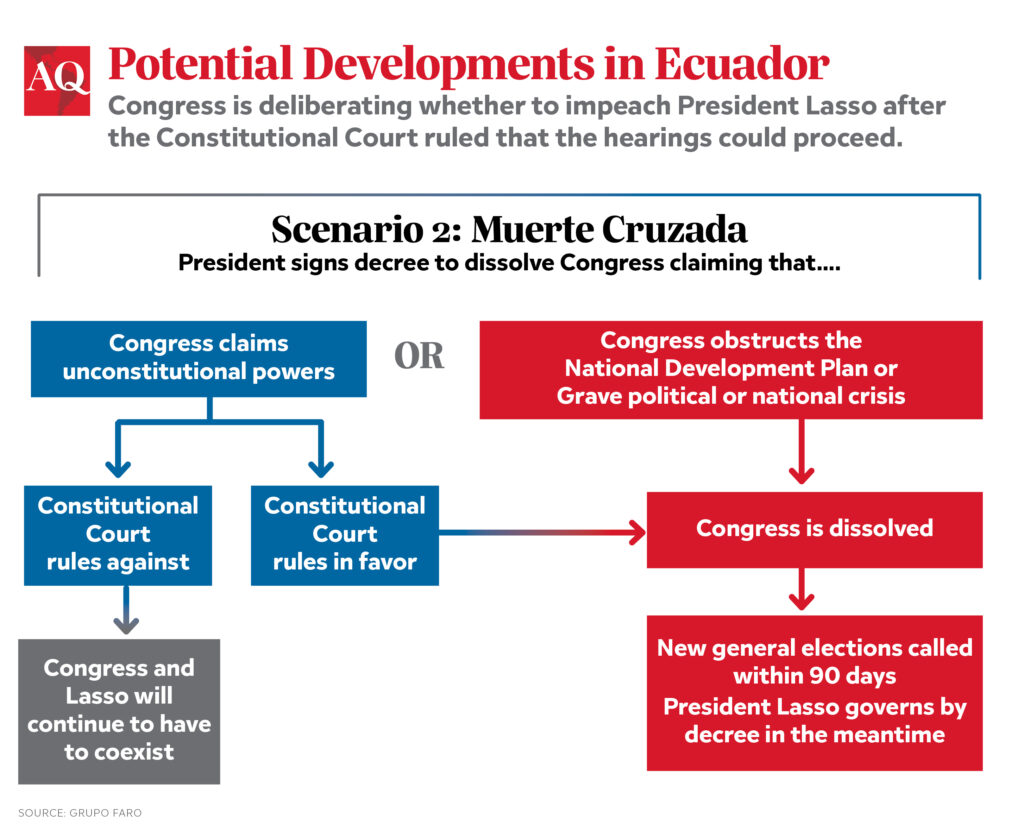

Another scenario involves the constitutional power of the Ecuadorian president to dissolve the National Assembly, known as muerte cruzada.

Enshrined in Ecuador’s 2008 constitution, in a process initiated during President Rafael Correa’s term, the muerte cruzada has not yet been invoked by any president. But given the current political climate, using this legal mechanism has become a potential reality.

Muerte cruzada has been a subject of debate since its creation, with some arguing that it can help solve governance crises from an institutional perspective, and that the mere threat or possibility of dissolution of the National Assembly could speed up decisions or allow for the expression of dissent before it spills over onto the streets. This mechanism was included in the Constitution with awareness of Ecuador’s history of riots that have caused premature ends to presidential terms: From 1996 to 2005, three presidents were overthrown: Abdalá Bucaram, Jamil Mahuad and Lucio Gutiérrez.

But others view muerte cruzada as a hyper-presidential measure that undermines the separation of powers and could exacerbate protests and social conflict—if, once applied, the government lacks capacity to govern and address the problems that led to the political crisis in the first place.

The muerte cruzada can be invoked in three situations: when the Assembly oversteps its constitutional competence, when it repeatedly obstructs the execution of the National Development Plan—a document the executive branch is required to present to the legislature for approval that includes national priorities and the budget—or when there is a severe political crisis and internal turmoil.

If the president dissolves the Assembly for one of the latter two reasons, no prior ruling from the Constitutional Court is required. Within seven days of the publication of the dissolution decree, the National Electoral Council must convene legislative and presidential elections to fill vacancies for the rest of the current term. In the meantime, subject to rulings from the Constitutional Court, the president can issue “urgent economic decree-laws” until new office-holders are installed. These officials’ terms will just fill the time left by the current office-holders, in this case until 2025.

With low approval for both the president and Congress, governance in Ecuador is complex; gaining public support and effectively implementing policies is difficult. The recent, opaque negotiations between different parties and the government reflect the broader challenge of establishing the kind of clear and transparent programmatic agreements that are essential for effective governance.

It remains to be seen how the situation in Ecuador will unfold and many questions remain unanswered. For instance, in the third scenario where the president stays in power, will he interpret that as a victory? What immediate measures will be taken to address problems such as insecurity, crime and unemployment that have fueled the political crisis? Are the opposition and the political parties aware of their incapability to pursue programmatic, transparent negotiations and agreements on solutions for the most urgent problems facing the country? The scenario for the next set of elections remains murky, whether they happen early or on schedule in 2025.