This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on trends to watch in Latin America in 2025

Correction appended below.

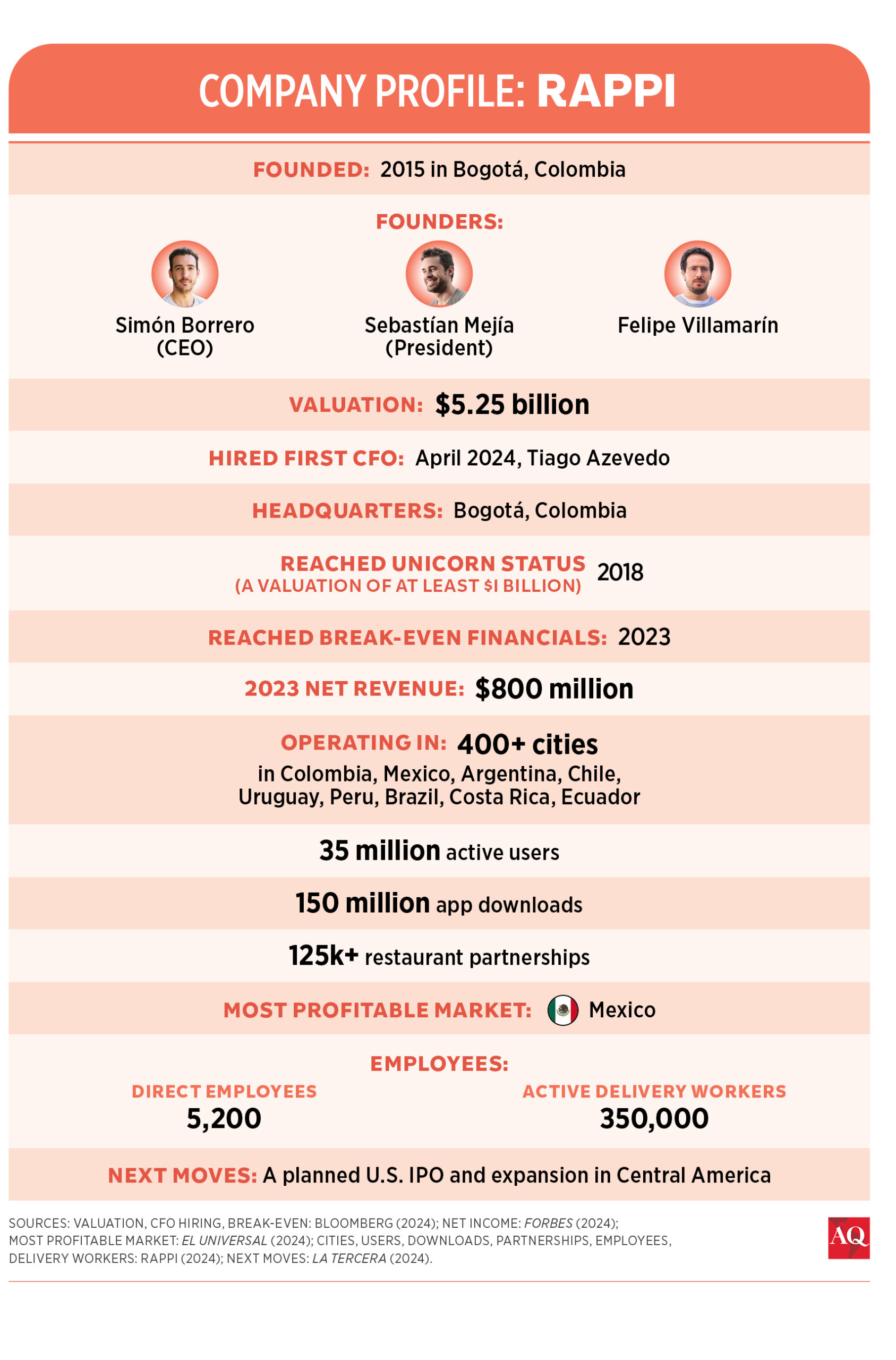

Since its founding in 2015 as a food-delivery service, Rappi has grown at a dizzying pace. In less than a decade, the Softbank-backed startup has morphed into a “super-app” with operations in nine Latin American countries and a market valuation above $5 billion—beyond, perhaps, the wildest dreams of its three Colombian founders. So far it has disrupted the region’s delivery and fintech sectors, and more is on the horizon.

The company has built a rising empire by taking supply chain efficiency and business diversification to new levels. Through its subsidiary Rappi Turbo, rolled out for stores in 2021 and restaurants in 2023, customers can order groceries or meals and expect them delivered within 10 minutes—an almost incomprehensible accomplishment in cities like Bogotá that have some of the worst traffic in the world. To make this possible, Rappi partners with hundreds of businesses, but has also pursued intensive vertical integration. Using algorithms to predict demand and manage performance, it has implemented its own robust networks of warehouses, cooking stations and personalized delivery for workplaces and households.

Although much of the global quick-delivery industry is struggling to find ways to grow—services like Gopuff and Gorilla in the U.S. and Getir in Europe are facing challenges—Rappi is preparing to go public over the coming year. The IPO, expected to take place in the U.S., aims to reinforce the sense that Rappi is just getting started.

Rappi has invested in AI to find new ways to streamline consumption and has embraced fintech. It has delivered credit cards to over 200,000 Colombians and savings accounts to over 300,000, offering the country’s highest interest rate of 14%. Beyond Colombia, the company provides financial services in Mexico, Brazil, Peru and Chile. Thanks to aggressive partnership campaigns, customers can use Rappi for everything from ordering medicines to online gambling and booking travel, and the list is growing.

Even as Latin American and Caribbean countries endure low growth, major progress on financial inclusion and the penetration of smartphone technology have facilitated Rappi’s exponential growth. In 2017, just 54% of the region’s population had a bank account. Today, the number is around 74%. From 2014 to 2021, mobile internet access exploded from 230 million to 400 million people.

This has resulted in a surge of platform-based work in the region that promises to upend labor relations. “In Latin America, we’ve already seen similar models of digital platforms start to disrupt other sectors from beauty to health care to education,” said Óscar Maldonado, a professor at Rosario University in Colombia and co-author of Fairwork reports on digital platform labor relations. “What is happening with digital delivery workers and drivers is just a precursor to something much bigger.”

Beyond fundamentals

Rappi’s three founders, Sebastián Mejía, Simón Borrero and Felipe Villamarín, worked in software development in the early 2010s and created Grability, a grocery shopping app that grew quickly in Latin America, Asia and Europe. They then leaped into the task of building an app to bridge shopping and delivery. A big break came in 2017 when Y Combinator—a U.S. VC firm focused on early-stage startups that has backed AirBnb, Twitch and Instacart—made Rappi the first Latin American company to receive its support.

Soon enough, Rappi embraced the move-fast-and-break-things ethos of Silicon Valley. By pushing boundaries, the company attracted fines for illegal promotions; investigations for withholding refunds and allowing minors to buy alcohol; and a long list of labor disputes from workers. But it also grew rapidly by focusing on algorithmic development.

In 2019, it received $1 billion from SoftBank, the largest tech investment for any Latin American company and the first from SoftBank’s “Innovation Fund.” The same year, it launched digital banking system RappiPay, setting itself up for major growth just before COVID-19 supercharged the delivery sector. By June 2020, capitalizing on the pandemic reality, the company announced a major expansion: a music streaming service, 150 mobile games, and a live events capability to sell virtual tickets to concerts and other shows.

But COVID-19 also brought challenges. Rappi received waves of bad press for becoming overwhelmed during Colombia’s Mother’s Day in 2020 and failing to deliver meals and gifts, inviting competition. Rappi proved resilient, in large part due to its diversification. It was ready to operate at a loss to win delivery market share, but also bought up competition, including Box Delivery and Avocado in Brazil, the Mexican payment system Payit, and others.

It also worked closely with AI companies to streamline service and predict demand. True to form, in September 2024, the company acquired one of those outsourcing firms, the Indian startup Fountain9, which it met through Y Combinator, showing its commitment to wielding algorithms and AI to boost efficiency.

Through aggressive expansion, Rappi’s sales in Mexico and Brazil overtook those in Colombia by 2023. But the company has been most dominant in its home country, where it commands a market share over 50% and has over 30,000 affiliated businesses and 3 million active shoppers. (Rappi’s communications office did not respond to requests for comment.)

An evolution on labor

Rappi’s labor practices still have detractors, but the company has moderated its positions markedly over the last two years, making dialogue and concessions to workers and regulators a steady part of its operations.

In 2023, the debate over what Rappi owes its rappitenderos in Colombia heated up as left-wing President Gustavo Petro pursued ambitious labor reform. That year, Rappi reported that around 130,000 rappitenderos, or delivery workers, used its platform in the country—a significant employment lifeline given Colombia’s 10% joblessness rate and 56% informality rate. Rappi also estimated that 40% are migrants, including many of the 2.8 million Venezuelans now in Colombia. “Rappi and other platforms like it probably saved the day for most of these migrant workers,” said Luis Fernando Mejía, the director of Fedesarrollo, a Bogotá think tank.

Rappi estimated last year that its rappitenderos earn an average of COP 11,000 ($2.65) an hour, well above the minimum wage of around $295 per month. That calculation, however, drew ire from critics for not accounting for significant expenses like gas and vehicle maintenance that could eat up half their daily earnings.

Facing various labor complaints, Rappi sat down with Colombia’s platform workers union (Unidapp) and the Labor Ministry. In September 2023 they reached an initial agreement and framework for further negotiation. Maldonado told AQ that Rappi’s attitude shift was partly due to Petro’s election. “When Petro’s administration took office, they realized that the regulatory environment had changed completely and that they had to start making concessions,” he said.

Now, the landmark legislation on delivery platform workers making its way through Congress seems to be something very rare: a win for business, workers, and Petro’s Labor Ministry alike, Mejía told AQ. It has Rappi’s support. If passed, Rappi would not have to pay workers a minimum number of hours, allowing them scheduling flexibility and the ability to seek work simultaneously with other platforms. For its part, Rappi would make social security and accident insurance payments.

The bill is set to become a defining guidepost for determining the benefits and protections that digital platform workers are entitled to. As apps worldwide disrupt full-time formal employment in favor of flexible and plentiful but often precarious gig work, Rappi’s journey in Colombia will be a reference case. “Rappi’s evolution on labor was a major, positive shift,” Maldonado told AQ.

—

This article was updated to clarify the net revenue figure, which was incorrectly labeled as net income.