Once again, Latin America seems to confront two visions for its future —this time with two competing viewpoints from North America. President Donald Trump and Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney present different scenarios for the hemisphere: one shaped by a U.S. sphere of influence, and the other by coalitions of middle powers that work together regionally while engaging globally.

Last year, in the U.S. National Security Strategy, the Trump administration reasserted the Monroe Doctrine, adding a “Trump Corollary”, which President Trump has dubbed the “Donroe Doctrine.” First articulated in 1823, the Monroe Doctrine warned European powers against interference in the Americas, while pledging U.S. non-interference in Europe. It emerged amid Latin America’s independence movements and the fear that Spain might attempt to reclaim its former colonies.

Trump’s version, however, is aimed less at Europe than at today’s great-power rivals—especially China, and to a lesser degree Russia and Iran. In this updated form, the doctrine asserts the Americas as a U.S. sphere of influence that Washington is prepared to defend, potentially by force.

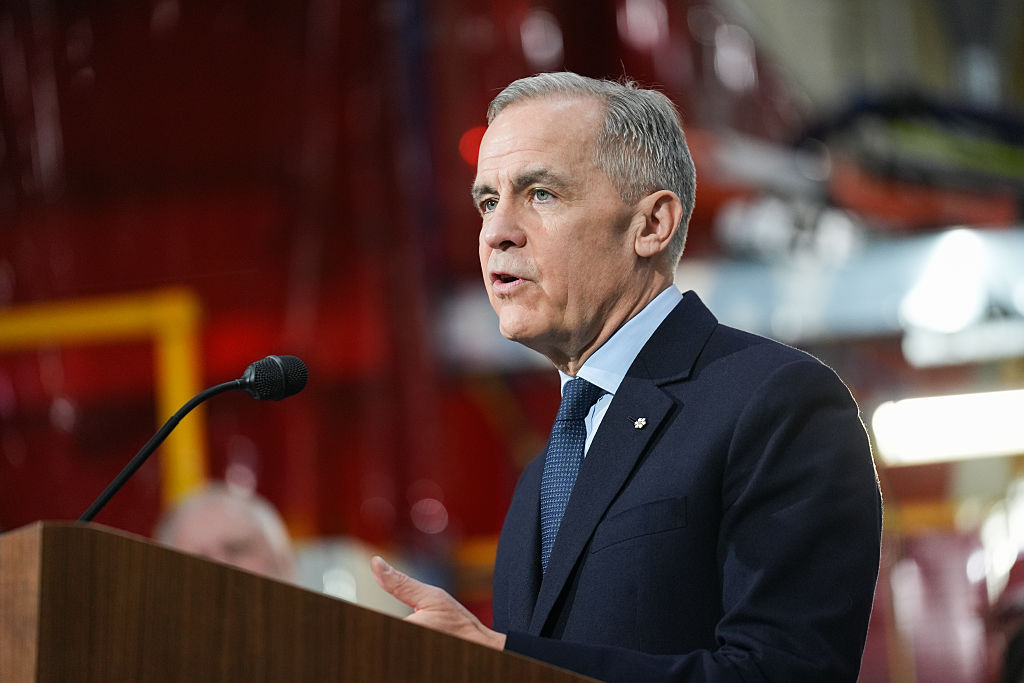

At Davos, Prime Minister Carney reclaimed the language of middle power for Canada. He called on middle powers to work together to sustain what remains of the rules-based order at a time when both the U.S. and China are challenging its institutions. The speech was global rather than explicitly hemispheric. But its implications for the Americas are clear: if Washington narrows the region into a strategic enclosure, Canada is signaling that other states should have options beyond alignment or isolation.

For that alternative to be more than rhetoric, Canada will need to demonstrate, in practice, what deeper hemispheric engagement entails. This could include expanding trade and investment ties beyond North America, strengthening development finance tools, and collaborating with partners such as Brazil, Chile, and Colombia on the energy transition and critical minerals supply chains. Ottawa could also leverage its G7 membership and relationships within multilateral institutions to amplify Latin American priorities, rather than treating the region as peripheral.

Latin America’s agency is central. Middle-power cooperation cannot simply be announced at the World Economic Forum; it must be built through concrete initiatives. A logical next step would be a leaders’ forum or summit of democratic middle powers in the Americas—anchored by Canada and key regional states—to coordinate on trade resilience, migration governance, and rules for external investment. Such cooperation would give countries greater leverage in dealing with both Washington and Beijing.

An early test

The upcoming USMCA review scheduled for July will be an early test of whether this opening becomes durable. In recent years, Canada has at times appeared tempted to pursue a bilateral accommodation with Washington, leaving Mexico exposed to U.S. pressure. But Carney’s early moves suggest a different course. He quickly reached out to President Claudia Sheinbaum, inviting her to the G7 summit he hosted in Kananaskis, and later made an official visit to Mexico to deepen ties. This is more sustained outreach than any Canadian prime minister has attempted in decades, arguably since Brian Mulroney.

The question now is not just whether Canada can demonstrate its seriousness, but whether Ottawa will maintain this hemispheric engagement—and whether Mexico and other Latin American governments will take the chance to diversify their diplomatic and economic options. Mexico, in particular, faces constant bilateral pressures from Washington that can overshadow other partnerships. Still, a coalition of middle-power countries will form only if nations look beyond short-term differences and invest in broader regional cooperation.

Carney’s message is likely to resonate in Latin America, where countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico all have plausible middle-power potential. These states already navigate great-power competition, balancing deep economic ties to the U.S. with growing Chinese trade and investment. A coalition model offers a way to preserve autonomy and influence without embracing imperial ambition or provoking direct confrontation.

Overcoming skepticism

For Carney’s middle power message to gain traction in Latin America, he may first have to overcome skepticism in the region about how committed Canada is to engagement with the region. After World War II, the U.S. encouraged Canada’s integration into the new global architecture—Bretton Woods, the United Nations, and NATO. Yet Canada remained only loosely tied to the hemisphere’s own institutions for decades, joining the Organization of American States only in 1990 and other inter-American bodies even later. Canadian internationalism developed more through transatlantic multilateralism than through hemispheric leadership.

It was in this context that Canada embraced the identity of a “middle power.” Middle powers—often democratic states with capable diplomats—found influence through coalition-building, norm-setting, and institution-building.

The deeper tension is not simply between Washington and Ottawa, but between two competing ways of imagining the hemisphere. Trump’s Donroe Doctrine suggests that the Americas are a strategic enclosure, and that even close partners like Canada are ultimately bound to U.S. power and priorities. Carney’s response rejects the premise of inevitable conflict, but it does not concede subordination. Instead, it casts the U.S. and Canada as natural competitors, each offering a model for how the Americas should relate to the wider world.

Canada is offering an alternative to U.S. dominance in the region, and it could be a competitive one, providing a share of leadership for countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico that Washington currently does not. This could prompt the U.S. to compete for Latin American support, or it could lead Trump to angrily isolate Canada from regional affairs and initiatives.

Will the Donroe Doctrine render the Americas a closed sphere of influence? Or will a middle-power vision open space for a broader inter-American dialogue, connecting the region outward rather than sealing it off?

It is too soon to know. But two centuries after Monroe, the U.S. is now a great power, the Americas contain many potential middle powers, and Canada has offered the region a contending alternative to U.S. leadership. The question is whether Ottawa—and Latin American capitals—will give that alternative concrete form.