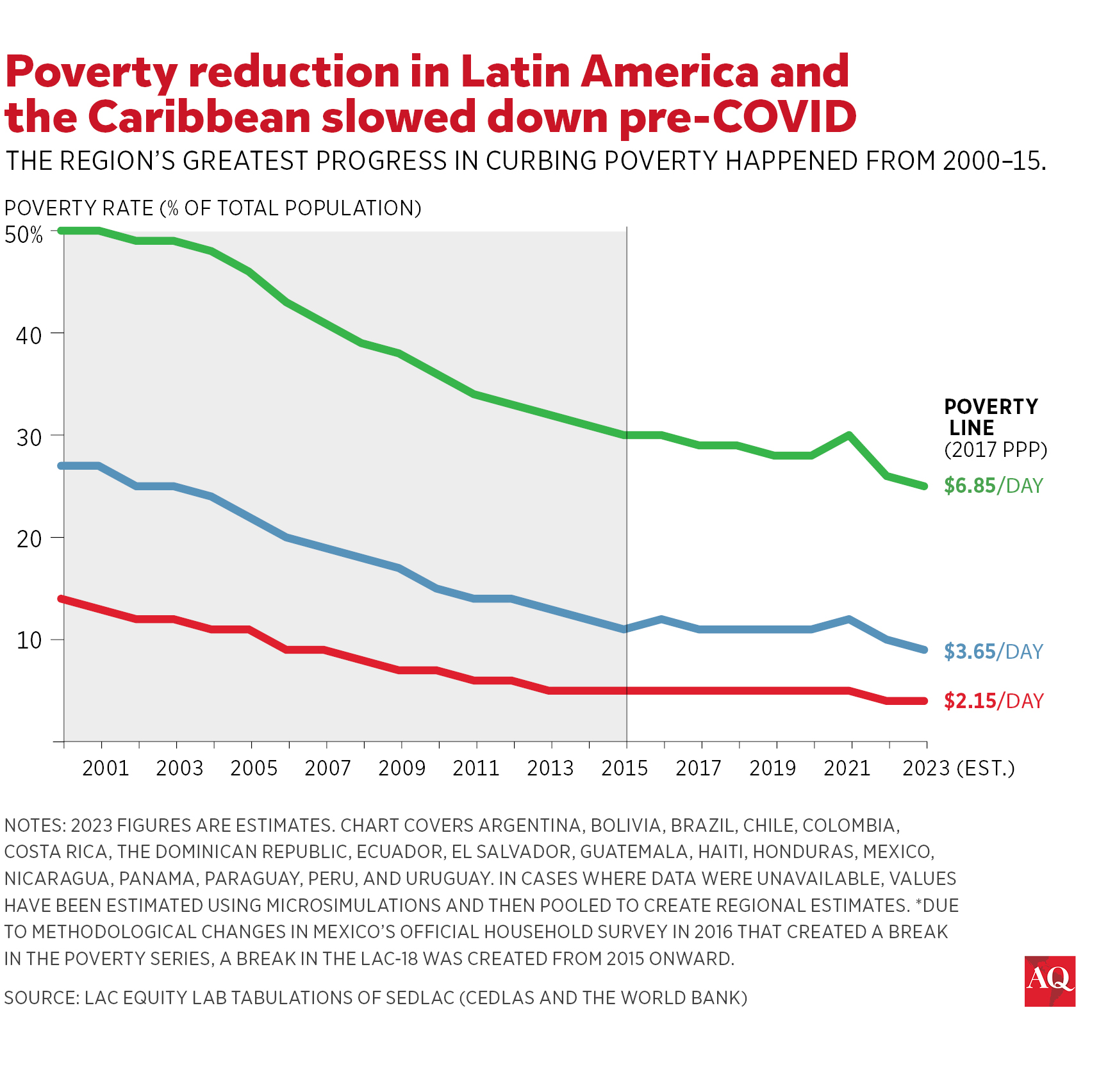

Latin America and the Caribbean has made undeniable progress in eradicating poverty in this century. In the early 2000s, about half of the region’s inhabitants lived in poverty, meaning in households with a per capita income of less than $6.85 per day (measured in 2017 dollars). Today, the proportion of people considered poor has decreased substantially—one in four citizens in the region lives in poverty—despite major macroeconomic shocks, climate disasters, and a global pandemic. While the advance is commendable, it’s not enough.

Looking at the data in the World Bank’s Regional Poverty and Inequality Update for Latin America and the Caribbean, a comprehensive annual report on the subject, one thing is clear: the region needs to regain momentum. Its greatest progress in reducing poverty occurred in the first 15 years of this century. Since then, improvement has been notably slower. The pandemic undoubtedly had an impact, but five years before COVID-19 hit the region, signs of a slowdown in poverty reduction were already evident.

The region’s overall poverty rate in 2019 was 28%. It peaked at 30% in 2021 and dropped to 25% last year. Today, poverty rates in the region are lower than those recorded before the pandemic. This is good news, but breaking down the numbers reveals pending challenges.

A closer look at the data shows that advances in Brazil and Mexico account for an important part of the progress made in the region’s poverty eradication. In Brazil, poverty dropped from 26% in 2019 to an estimated 22% in 2023. This reduction is largely attributed to the expansion of the Bolsa Familia program, but there was also a notable rise in labor incomes. In Mexico, poverty fell from 28% to 21% during the same time frame, with a clear pro-poor growth in labor income with increases in both formal and informal wages. Notably, minimum wages had a “lighthouse effect” in the informal segments of the economy.

However, in about a third of the region’s countries, poverty rates are still above pre-pandemic levels. This includes countries from the Southern Cone, the Andean region, and Central America.

Inflation is a critical element that explains why poor segments of the population have seen their real incomes drop in many Latin American countries. Rising inflation affected poorer populations’ consumption baskets, and since food inflation was higher than that of other products and services in the post-pandemic years the purchasing power of the poor has deteriorated more than that of the non-poor. Real incomes have also fallen as income transfer programs for the poor that were created or expanded during the pandemic have gradually faded away.

A third element is labor income, which accounts for around three-quarters to four-fifths of households’ incomes, depending on the country. However, labor income has not changed uniformly across income levels. For example, in El Salvador, labor income for the average citizen increased, but that of the poorest three income deciles dropped. This highlights the importance of a distributive approach when assessing peoples’ wellbeing, analyzing beyond average indicators.

Another indicator deserves special attention: job informality. Formal jobs are crucial to fighting poverty because they tend to be associated with other desirable conditions, such as job stability, income security, social protection, and higher earnings. Nevertheless, World Bank data shows that only one in three jobs in the region is formal. Among the poor, however, the formality rate is close to zero, both for self-employed and salaried workers.

The role of public policies

How can the region regain momentum to continue reducing poverty? First, improved macroeconomic conditions are needed. This starts with controlling inflation (“a tax for the poor”), but it goes beyond it. Countries need to regain economic growth to create more and better jobs. The success story of the first fifteen years of this century is associated with the strong growth Latin America and the Caribbean had during that time. Between 2000 and 2015, the average annual growth rate for the region was 2.8%, but between 2015 and 2023, it was just 0.7%.

The need for renewed growth is clear, but a fresh approach is necessary. The World Bank’s 3i strategy, focusing first on investment, then on the infusion of new technology from abroad, and then on innovation, should improve productivity and job creation. South Korea is the paradigmatic example of such strategy; Poland and Chile are also worth highlighting.

The second set of policies should aim to support poor and vulnerable households to access good jobs and to complement their incomes when needed. Around one-fifth or one-fourth of household income comes from non-labor sources. For the poor and vulnerable, most of the non-labor income comes from the government through cash transfers. This has been the case in pandemic and non-pandemic times, and it clearly shows how important transfers are for those households’ incomes.

When fiscal constraints are pressing, governments need a new approach. The challenge is finding ways to improve transfer-targeting mechanisms to increase efficiency. Taking advantage of big data and reloaded computational tools, countries should be able to identify better who needs support, when it is required and how to deliver it. In this way, adaptative social protection networks are achievable goals, with agile capabilities to scale up and down as needed.

Labor income is the third essential element for combating poverty. For any household, the second-most important predictor of leaving poverty is that one of its members moves from unemployment to a full-time job. Getting a formal job is the most significant predictor. The 3i strategy requires supporting the poor so they can access quality, formal jobs. There are short and medium-term options for that.

In the short term, governments could help poor workers to be aware of job opportunities and support them in preparing for job interviews. Active labor market policies will be very useful, especially those on job intermediation. For the medium term, the strategy must be complemented with investments in human capital accumulation. This involves skills development along the life cycle, for which investments in infrastructure and the teaching profession are seriously needed.

Latin America and the Caribbean have previously shown that they can make significant progress in reducing poverty in a short period of time. Returning to that path requires adjusting and improvements to evidence-based public policies. Updated data provide us with a clear roadmap. Now is the time to act.