On the eve of Brazil’s Oct. 2 mayoral elections, São Paulo woke up to find one of its most beloved public sculptures – the Monument to the Flags, commemorating the city’s 400th anniversary – slathered in turquoise, red and yellow paint. Sensing opportunity, candidate João Doria rushed to the scene to film a Facebook video denouncing the incumbent mayor for failing to stop the crime. Then, Doria took a step toward the camera, jabbed his finger and delivered an ominous warning: “I’m here to tell you, vandal, you, graffiti guy, this is going to end! … This leniency is over! This ‘do whatever you want’ in São Paulo. With me, no! It’s time for authority!”

Only a year ago, Doria’s police sergeant-like tone might have been deemed as too reaça, too reactionary for Brazil’s largest and most cosmopolitan city. But not in the Brazil of 2016, a country plagued by rising crime and seemingly interminable recession and scandal. The next day, Doria won the mayorship in a landslide with 53 percent of the vote, capping a meteoric rise for a wealthy but relatively obscure business leader with no prior experience in elected office. To the surprise of even his aides, Doria triumphed in 56 of São Paulo’s 58 electoral districts, indicating broad support from rich and poor voters alike. The vandalism of the monument, and Doria’s stern rebuke, played a clear role in his last-minute surge – as of today, the Facebook video has been seen 2.7 million times.

Doria’s victory, plus wins by similar candidates in runoff elections on Sunday, confirmed a shift toward a more conservative, authoritarian brand of politics in Brazil. Some degree of this is happening the world over, of course, with the most prominent example another right-wing businessman who may well be elected president of the United States on Tuesday. But Brazil’s experience is somewhat different because it contains echoes of the not-so-distant past – the era between 1964 and 1985, when Latin America’s largest country was ruled by a military dictatorship. Nostalgia for that period, or at least for some of its tactics and overall worldview, is at its highest point in many years. And that poses risks not only for things like human rights and freedom of speech, but also fundamental changes to the way Brazilian politics will be conducted through 2018 and possibly beyond.

To be clear, I am not accusing Doria or any other politician of being anything less than fully committed to electoral democracy. Brazil is in precisely zero danger of returning to military rule, partly because the generals were so discredited by their two decades in power, and partly because the Cold War is over and the world has changed. Many Brazilian institutions, particularly within the judiciary, remain the envy of other Latin American nations. But the political environment in which today’s leaders operate has dramatically shifted in a short period of time – and with that comes the danger of abuses and other overreach, some of which is unfortunately already happening. But more on that in a moment.

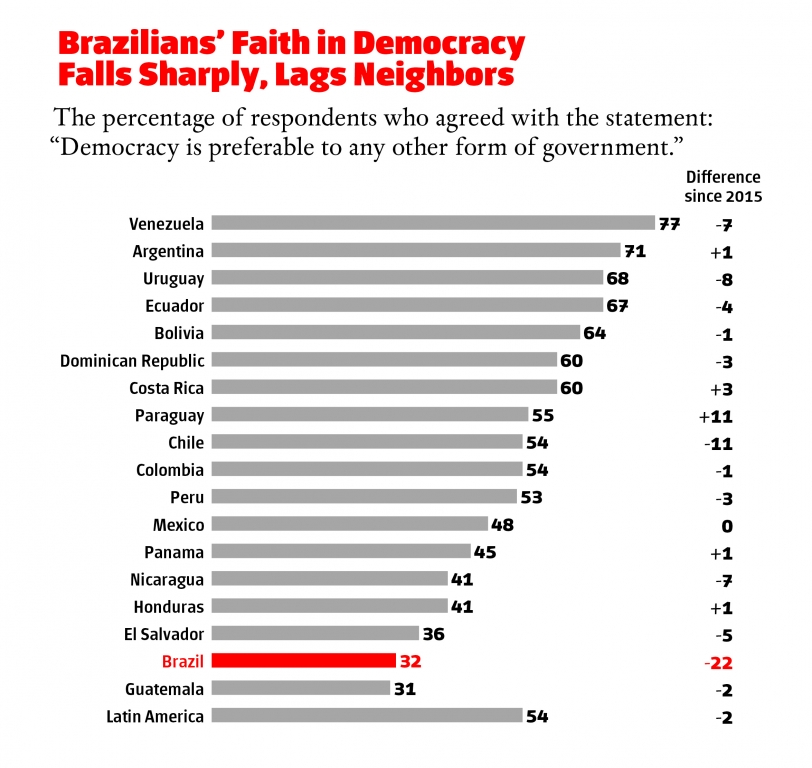

For empirical evidence of the changing mood, consider the chart above, drawn from a survey released in September by Latinobarómetro, a Chilean pollster. Every year, it asks people across the region whether they agree with the statement: “Democracy is preferable to any other form of government.” In 2016, just 32 percent of Brazilians agreed – a whopping 22 percentage point decline compared to 2015, by far the largest drop of any country in the survey. Only Guatemala – a country so plagued by violence and poverty that tens of thousands of its people flee every year – registered less support for democracy in 2016 than Brazil. Meanwhile, the number of Brazilians who agree that “I don’t mind a non-democratic government as long as it solves problems” rose to 55 percent – defying a downward trend across Latin America as a whole.

The reasons for this shift are fairly obvious. In the minds of some Brazilians, the worst recession in at least a century and the discovery of billions of dollars in graft at Petrobras and elsewhere have discredited not just the entire political class, but “democracy” as a whole. This may sound like an overreaction – and it is – but remember that Brazil’s democracy is barely 30 years old. Most of that period has been dominated by center-left governments of varying stripes which during the 1990s and 2000s successfully brought tens of millions of Brazilians out of poverty, virtually eliminated hunger, and consolidated many democratic institutions. But in a “What have you done for me lately?” kind of world, they are now collectively blamed for unemployment above 11 percent, some of Latin America’s highest taxes, seemingly daily revelations of corruption, and a horrifying 58,000 homicides per year.

There is nothing inherently wrong with the pendulum swinging to the center-right or right; new ideas and faces are desperately needed in Brazilian politics. The problem is that, especially following President Dilma Rousseff’s controversial impeachment in August, some Brazilians in both politics and everyday life seem to have concluded: “Thank God, now we can dispense with all that wishy-washy democratic nonsense,” and revert back to the way things were done prior to the 1990s.

There have been numerous high-profile examples of this, including last month’s election of Carlos Bolsonaro, the scion of a family that openly expresses nostalgia for dictatorship and torture, as the city councilman with the most votes in all of Rio de Janeiro. A former mayor of Curitiba who recently complained that he vomited the first time he gave a poor person a ride in his car will get his old job back anyway, thanks to a campaign built around nostalgia for the 1990s and the slogan “I want my Curitiba back.” Elsewhere, a judge’s September decision to throw out the murder convictions of 74 police officers in a 1992 prison massacre that killed 111 inmates was widely seen as a reflection of the current political moment – and deemed by Amnesty International a “terrifying message about the state of human rights in Brazil.” Also in September, on the first Sunday following Rousseff’s impeachment, the São Paulo state government declared it would ban anti-government protests from the city’s main thoroughfare – before then backtracking under public pressure.

There have been other, less noticed cases as well: The Saturday night before the mayoral elections, police in Rio arrested two well-known journalists who were filming an eviction in a favela, a move the New York Times’ Brazil correspondent called “very troubling for freedom of the press in Brazil.” September was “by far” the month with the highest number of legal actions filed by politicians trying to force media outlets to withdraw unfavorable stories since ABRAJI, a journalism group, began tracking such cases in 2002. And just this week in Santos, the port city south of São Paulo, military police halted a street performance by a theatrical troupe that was making fun of… the military police. They confiscated the group’s sound equipment, props and cell phones and arrested one of its actors on a charge of “disrespecting a national symbol” – the Brazilian flag.

Viewed in isolation, such incidents are not necessarily so disturbing or even all that new – but taken together, they paint a picture of changing values and power dynamics. Raquel Rollo, an actress in the ill-fated troupe, told Folha de S.Paulo they had given the same performance at least 20 times in the same plaza. “But there was never anything like that,” she said, seemingly puzzled. Well, previously there wasn’t a rising political star up the road saying things like “It’s time for authority!” Everybody in Brazil – police, Congress, the courts – senses who and what is ascendant right now.

It’s still possible that Doria will govern as a more traditional law-and-order figure, a Brazilian Rudy Giuliani. Similarly, it’s possible that President Michel Temer will resist the authoritarian impulses of some within his ranks who, for example, are telling him he doesn’t need support from society at-large to pass long-term reforms to Brazil’s budget and pension system. It’s also possible that diminished enthusiasm for democracy is only a short-term phenomenon caused by a truly awful recession. Indeed, in the 21 years since Latinobarómetro began polling, support for democracy in Brazil has fallen this low once before – in 2002, another moment of high unemployment and uncertainty. When the economy bounced back, so did civic spirit.

But… I’m not so sure. I was in São Paulo last week, and I came away with two surprises. One was the level of desperation on the city’s streets – an explosion in the number of people sleeping in tents and under bridges compared to just four months before. The other surprise was the total lack of enthusiasm for potential successors to Temer in 2018. Americas Quarterly recently published a list of 10 possible candidates, from a variety of backgrounds and ideologies. Brazilians kept begging me to put it away – “That list makes me want to cry,” one lawyer said. Indeed, given the dearth of inspiring options, and the expectation that the next round of plea-bargain testimony in the Petrobras case will mortally wound another wave of politicians, much of the buzz around 2018 was centered around a new face, a political outsider who could continue his rise and conquer the highest office in the land. His name: João Doria.