In 2003, Bolivia was in crisis.

A bloody crackdown on weeks of protests had forced President Gonzalo “Goni” Sánchez de Lozada to flee the country. In his place stepped Vice President Carlos Mesa Gisbert, a relative newcomer to politics who nevertheless won early support for his promises to lead a transition government for the divided country.

But less than 20 months later, Mesa had resigned, his short-lived presidency serving as a segue to 14 years of rule by his government’s chief opponent, Evo Morales.

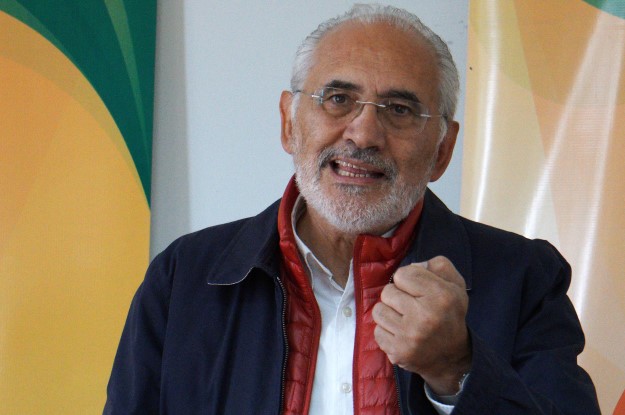

Today, Bolivia is again in trouble – roiled this time by Morales’ controversial fall from power, a devastating pandemic, discredited institutions, and an economic crisis – and it’s in this context that Mesa is running for president, seeking a second chance to try to lead the country to brighter days.

If the Oct. 18 election goes smoothly, Mesa, now 67, has a good shot at returning to the presidential palace in La Paz. Interim President Jeanine Áñez’s withdrawal from the race increased the likelihood that Mesa will make a runoff vote against Morales’ former economy minister, Luis Arce. It’s a matchup that polls suggest Mesa, who finished second in last year’s contested vote, would win. But there are many questions about where Mesa would try to take Bolivia, and how he would unite a country fragmented geographically, racially, economically and politically.

Given the ways both he and the country have changed since he left office, a Mesa presidency could look quite different than it did 15 years ago.

For starters, experts say Mesa’s politics have changed, thanks in part to broader transformations in Bolivian society.

“He’s moved to the left,” said Diego von Vacano, a Bolivian political scientist at Texas A&M University. “That’s mainly because Morales shifted the entire spectrum of Bolivian politics to the left.”

But Morales’ final years in office damaged his Movement toward Socialism (MAS) party’s reputation among sectors it had come to rely on, creating an opening for Mesa, who has courted indigenous and environmental leaders disillusioned with MAS’ environmental policies. Mesa’s electoral alliance is also ahead of other coalitions when it comes to fielding female candidates in October’s election.

“Mesa is trying to maintain a big tent where there is representation within his alliance,” said Devin Beaulieu, an anthropologist and expert on indigenous issues based in Sucre.

“Mesa is the only candidate who has stated a willingness to open a national debate on gay marriage, abortion and marijuana legalization,” Beaulieu added.

What you get is a candidate who looks different from the right-wing politics he became associated with as vice president to Sánchez de Lozada, a U.S.-raised businessman known for privatizing state enterprises as president.

“Mesa was sort of an accidental vice president to Goni (Sánchez de Lozada),” said von Vacano. “I don’t think he himself was a leader of the ideology behind Goni’s privatization and neoliberal approach.”

Jorge Derpic, a Bolivian sociologist and professor at the University of Georgia, told AQ that Mesa isn’t likely to stray drastically from the state-led economic model Morales pursued as president.

“MAS changed the way we see privatization and the role of the state in the economy,” Derpic said. “I don’t think Mesa has any interest in fostering the privatization approach.”

Mesa has said as much in interviews, including one with AQ in 2019, when he stressed that Bolivia needs more foreign direct investment, but “by no means does this mean privatization.”

“MAS tries to link Mesa with Sánchez de Lozada all the time, but I think that Mesa is a different animal today,” said Derpic. “In some aspects, he has a more progressive agenda than MAS has had during the last decade.”

Potential roadblocks

Experts who spoke with AQ warned that Mesa’s agenda at times seems overly vague and may be difficult to implement.

“I can’t tell you what his economic plan is,” said Eduardo Gamarra, a professor at Florida International University and expert on Bolivian politics. “There’s a lot of things he says that make him sound very intelligent, and I think he is, but I don’t really see much substance there.”

Mesa’s success will also depend on whether he’s learned to navigate politics once in office.

A celebrated journalist and historian who studied literature in Madrid, Mesa had no political party or experience in elected office when he became vice president in 2002. He is seen by some as distant and elitist. When he was president, Mesa struggled to assert control in Congress and on the streets.

“When he was recruited by Goni, he was an outsider who was above politics,” Gamarra said. “Today, with insight, we know that one of the biggest problems for outsiders is that they have no institutional capacity to act.”

Still, María Paz Salas, the president of the Bolivian Association of Political Science, told AQ that Mesa “has been here before and he’s learned lessons.”

Salas points to an interview in 2017, in which Mesa said he failed to understand “the essence of politics” as president.

“I mistakenly believed that in the role of a historic transition, I was required to be neutral,” Mesa said. “I later learned that neutrality doesn’t exist in politics.”

Still, Mesa has been criticized at times for not taking sides during the political conflict of recent months. Mesa has walked a tightrope in his criticism of Áñez – criticizing her electoral bid, for example – while keeping a clear anti-MAS position.

“He has been careful about not exacerbating anger on both sides,” said Derpic.

It’s an approach that didn’t exactly work for Mesa during his presidency, in which he took some steps to close the gap with the opposition, supporting, for example, a constituent assembly to rewrite the constitution and signing a decree that granted amnesty to Morales and others involved in the 2003 unrest.

“Mesa had this vision that he was not a transitional president, but a transformative president,” said Gamarra. “But Morales and others saw him as merely transitional.”

Still, Mesa’s willingness to play the center could also work to his advantage this time around, and may help him bring the country together if he’s elected next month.

In fact, Mesa’s willingness to work with his opposition aided his comeback. In 2014, Morales tapped Mesa to be the government’s international spokesman for Bolivia’s lawsuit against Chile in the International Court of Justice, in which Bolivia unsuccessfully petitioned Chile for access to the Pacific Ocean. The case gave Mesa a platform on which to raise his profile as a diplomatic statesman – an image that could aid him should he soon find himself again leading a nation going through a rocky transition.

“Mesa will have an extraordinarily difficult time governing a country that is so polarized. The only way to overcome such polarization is by repopulating the political center,” said Gamarra. “Mesa may be the only one capable of now reaching out and building that bridge over the empty middle.”