SANTA CRUZ—With Bolivia’s August 17 general elections approaching, question marks abound. But one thing is clear: They will mark the end of the Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS) party’s overwhelming dominance and its program of economic populism.

The MAS and its grassroots bases are still collectively a powerful leftist political force, but polling indicates that the era of its legislative majorities and broad popular appeal is over, and it is no longer the party most likely to secure the presidency. Fractures within the MAS are growing, and opposition figures are gaining momentum. This is creating opportunities for centrists, the right, and a new leftist faction led by Senate President Andrónico Rodríguez, who was a MAS leader before the party splintered.

All this means that the elections are virtually certain to usher in a new political landscape in which power is more diffuse, any legislative majority will be conditional, and broader coalitions will be required to govern.

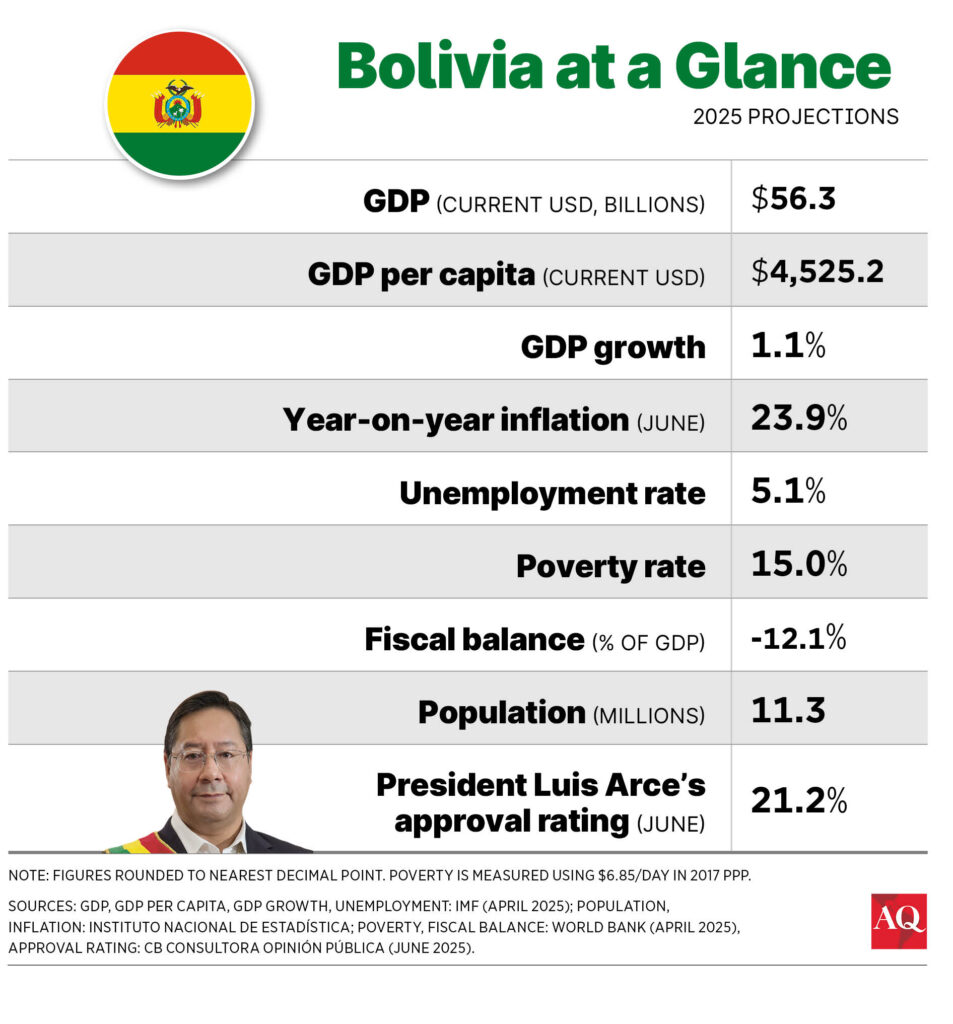

Regardless of who wins, coalition-building will be just one of many major challenges to governability. President Luis Arce, elected in 2020 on the MAS ticket, has led the country into its worst financial and economic crisis since the hyperinflation of 1985, and the country will likely take years to recover. Until then, prolonged instability appears almost inevitable.

Dire straits

During the boom of gas exports to Brazil and Argentina that occurred during Evo Morales’ presidency, the MAS enjoyed broad popularity for its programs of economic distribution to regional and municipal governments. These programs helped to reduce poverty, especially in the most marginalized areas of the country, albeit in some cases just temporarily. This period of government largesse based on abundant natural resource revenue, however, has come to an end.

Gas revenue has plummeted due to economic mismanagement and a lack of investment, and the country’s foreign currency reserves have declined from over $15 billion in 2014 to under $2 billion today. Most of that is gold, with as little as $47 million left in hard currency, according to Fitch Ratings, which downgraded Bolivia to CCC- status in January. The CCC- rating indicates a very high level of credit risk, suggesting a significant possibility of default on national debt obligations.

For ordinary people, prices are rising sharply; the IMF projects 15.1% inflation for 2025. Gas shortages regularly force drivers to wait many hours at the pump, and the government is still enforcing an exchange rate of 6.96 bolivianos to the U.S. dollar, while the black-market exchange rate hovers around 14.

Morales’ personal fortunes have fallen just as hard. President from 2005-2019, he is now a fugitive from justice, accused of fathering a child with a 15-year-old girl in 2015 and related charges, including statutory rape. He denies wrongdoing and has said the charges are politically motivated. And even though Morales insists he should be able to campaign for president this year, the constitutional court ruled unanimously in May that no person can run for a third presidential term, effectively barring him from the race.

Presidential contenders

The MAS now has three main factions jockeying for power. Arce, who has opted not to run for reelection due to his dismal approval ratings, is backing his former Interior Minister, Eduardo del Castillo. However, polling indicates that he has failed to gain traction. MAS maverick Eva Copa, the 38-year-old mayor of El Alto who has often bucked the party, leads a second faction of Arce dissenters, but she is similarly lagging in the polls.

The MAS candidate with the best prospects is Senate President Rodríguez, the 36-year-old former right-hand man to Evo Morales. He is trying to brand himself as a new kind of MAS leader who can reconcile with the opposition, crack down on corruption and abuse of power, and undo the economic mismanagement of the past decade. Andrónico, as he is popularly known, has been unwilling to take firm stances on the MAS’s internal disputes, and chose Morales’ former Planning Minister Mariana Padro, a middle-class professional, as his running mate. Still, Morales has thus far withheld public support for Andrónico.

The divisions within the MAS give the opposition its best chance since 2005 to win a national election. However, the opposition is itself also very fractured. Its three leading candidates—business magnate Samuel Doria Medina, former President Jorge (Tuto) Quiroga, and Cochabamba Mayor Manfred Reyes Villa—have all spent decades in politics and are unlikely to drop out.

All this indicates that the presidential election will likely result in a competitive head-to-head runoff on October 19 between Andrónico—who is likely to win support from rural voters less likely to be captured in polling—and one of the opposition candidates.

Instability ahead

The legislative result will be much more mixed. While hard to predict, the MAS majorities in the upper and lower chambers are likely to shrink considerably. If they survive, they will be narrow. If they do not, the opposition may be able to coalesce into a governing coalition, although this is also uncertain.

What is certain is that there will be no quick fix to the dire economic situation. If new natural gas and lithium exports are to materialize, this will take time. If meaningful efforts to cut government spending are undertaken, they will be met with intense protests.

A two-decade political cycle is drawing to a close. It is giving way to the next, which seems sure to begin with several years of protracted instability.