This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on China and Latin America

VALE DO JAVARI INDIGENOUS TERRITORY, BRAZIL—The next round of the UN Climate negotiations will be held in November in the Amazon, where scientists have accumulated indisputable evidence that the rainforest is a critical stabilizer for the global climate. It stores carbon, produces rainfall, and its unparalleled biodiversity is still yielding new discoveries. All the while, climatologists warn that deforestation and planetary warming are pushing the Amazon toward a tipping point of irreversible collapse.

As satellite imagery and geospatial data have become more sophisticated, they have made clear that Indigenous territories, which make up nearly a quarter of the Brazilian Amazon, play an outsized role in holding back the advance of deforestation.

The wealth of resources in these territories has placed them squarely in the crosshairs of ranchers, land speculators, timber thieves, powerful politicians aligned with agribusiness and the mining industry, and even missionaries in search of souls to evangelize. Even so, viewed from space, Indigenous lands remain islands of deep green abutted by denuded scrub, pastureland and monoculture plantations.

All this shows that the decades-long campaign to protect Indigenous territories in the Amazon has been critical for both preserving its forests and mitigating global climate change.

The Javari Valley

The Vale do Javari Indigenous Territory in far western Brazil plays a unique and pivotal role in this equation. Covering 33,000 square miles (85,444 square kilometers) and roughly the size of Portugal, the Javari Valley reserve has retained a remarkable 99% of its original forest cover, sheltering a dazzling abundance of fish and wildlife. Its stream-laced forests and rugged interior harbor around 6,300 people, including at least 11 and possibly as many as 16 isolated Indigenous communities, making the Javari home to the largest concentration of so-called “uncontacted tribes” in the world.

But “uncontacted” is something of a misnomer. All such communities have had at least glancing contact with the outside world, and it’s often been deadly. Like elsewhere in the Amazon, the groups in the Javari are believed to be the descendants of survivors of violent clashes with European intruders, including slaving raids that convulsed the western Amazon during the rubber boom of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The survivors fled into the jungle’s deepest, most inaccessible redoubts and continue to shun contact with the outside world. The isolated groups seem to possess an awareness of the mortal dangers posed by strangers, either from their firearms or from communicable diseases to which they have little to no immunological resistance.

In the 1980s, after more than a century of cataclysmic encounters for isolated tribes across the Amazon, field agents within FUNAI, Brazil’s Indigenous affairs agency, pushed for a groundbreaking new policy that bans outsiders from making contact with such communities. That policy aligns with Brazil’s 1988 Constitution, which recognizes the right of Indigenous peoples to practice their traditional ways of life in their homelands free from persecution.

In 1996, officials drew up the boundaries of the Javari Valley Indigenous Territory to protect this right for the area’s isolated communities. All its major waterways originate in a latticework of gulleys and creeks deep inside the reserve. FUNAI was thus able to secure the territory from large-scale intrusions with the placement of strategically positioned checkpoints along those rivers.

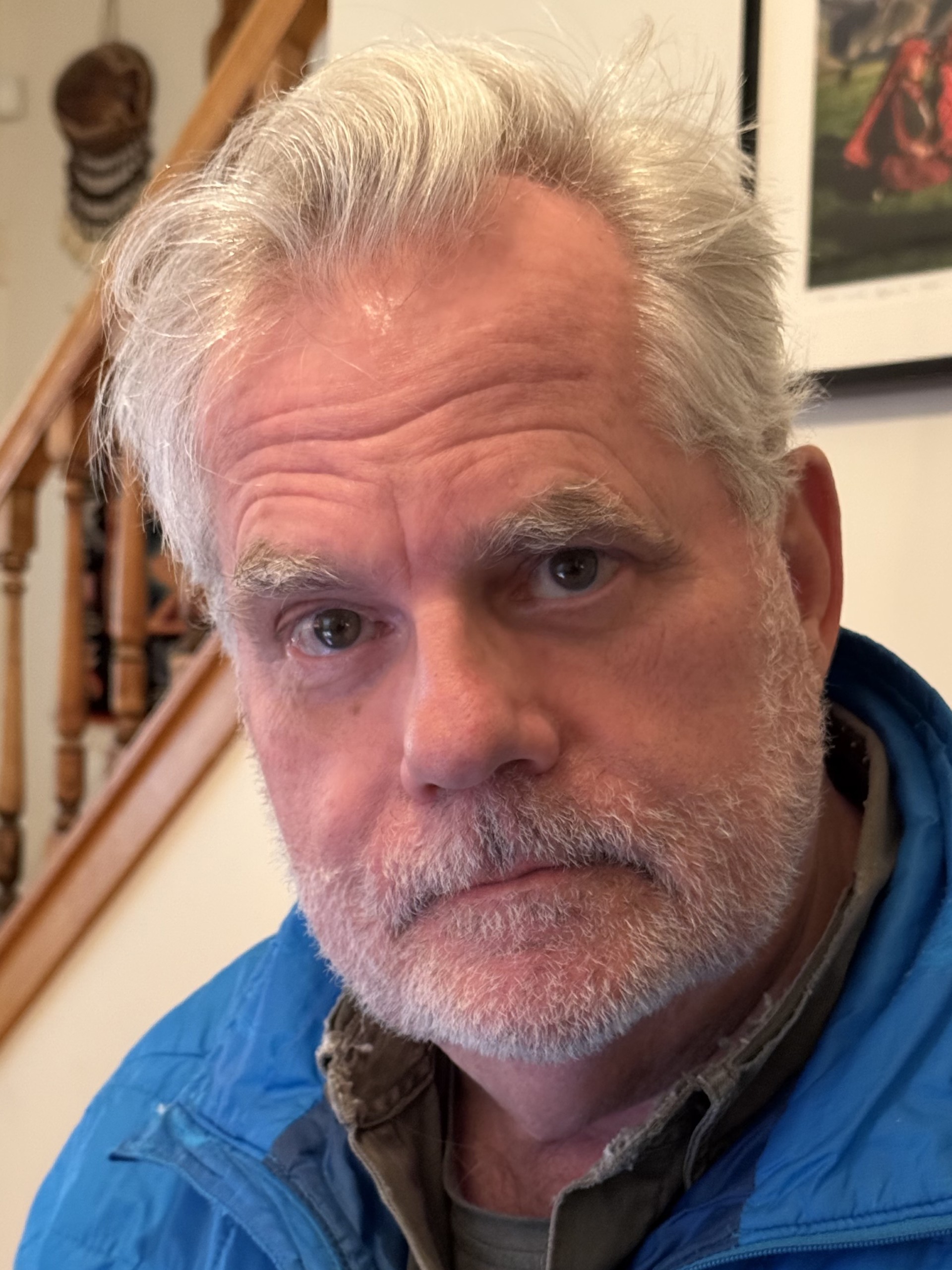

“When the Javari reserve was demarcated, it was done [partially] to protect all these waterways,” said Sydney Possuelo in 2002, when I trekked with him for nearly three months through the far reaches of the Javari on a Brazilian government expedition to check the well-being—but not make contact with—one such tribe, the seldom-glimpsed fleicheros.

Possuelo, a legend ary explorer and former FUNAI president, had pushed hard for the agency’s no- contact policy and founded an elite unit within FUNAI to protect isolated Indigenous groups. He is intimately familiar with the Javari Valley, having led expeditions into its depths while helping direct the uphill fight to enforce its boundaries alongside “contacted” Javari communities.

Transformation

Since the expedition in 2002, I have seen the Javari undergo a profound transformation, particularly in the past 15 years. Located in the tri-border region that Brazil shares with Peru and Colombia, its strategic but remote location caught the eye of drug traffickers looking for unpoliced routes to move product east toward Manaus and Belém and on to markets in Europe and North America. Meanwhile, non-Indigenous populations living along the Javari’s frontiers, including settlers who had been expelled from the territory in 1996, have slipped deeper into destitution after losing access to the fish, game and timber that supported their livelihoods.

This state of affairs has given rise to seething resentment among frontier communities near the Javari and other Indigenous reserves. Their anger has been stoked by populist politicians like former President Jair Bolsonaro, who has often repeated the mantra that “there is too much land for too few Indians.”

During his tenure, Bolsonaro severely crippled FUNAI and the environmental protection agency, IBAMA. He emboldened supporters to take the law into their own hands, slashed budgets and career staff, and installed like-minded loyalists in key posts. Deforestation rates skyrocketed. Invasions of Indigenous lands surged. Environmental crime—and organized crime—flourished across the Amazon, including inside the Javari.

Bolsonaro lost his bid for reelection to President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in 2022, and robust policing of Indigenous lands and protected areas has since resumed to some degree. But the effects of Bolsonaro’s policies continue to reverberate.

A new Indigenous initiative

The repercussions came into sharp focus for me when I returned in July. Amid concerns over security, I was the only journalist invited by the Union of Indigenous Peoples of the Javari Valley, Unijava, to attend the first-ever general meeting of a 112-strong Indigenous vigilance force (Equipe de Vigilância da Unijava, EVU). In six separate teams, the force will monitor the major rivers that serve as the principal infiltration points for a panoply of intruders: drug traffickers, gold miners, poachers, even guides from Peru sneaking in European tourists to view exotic “natives” and wildlife.

The meeting was a historic moment. It was the largest gathering ever held inside the territory of a multiethnic Indigenous force drawn from “contacted” communities throughout its far-flung reaches. The participants came to share experiences and receive training in everything from satellite communications, geospatial mapping and drone surveillance to boat maintenance and first aid.

Not long ago, such work would have been the exclusive domain of federal agents, with limited participation from local communities. But the power vacuum produced by the retreat of FUNAI, IBAMA, and other enforcement agencies from the field spurred Indigenous leaders to find a new way forward.

“We had no choice,” said Beto Marubo, director of the Union’s international relations, recalling early discussions that led to creating the homegrown force to counter a growing influx of outsiders seeking to involve Indigenous communities in their illicit trades. “If we didn’t act, we’d have lost our resources. There wouldn’t have been anything left even to feed our families.”

The two-week meeting took place at a newly built training center on a bluff overlooking the Quixito River on the northern flank of the territory. The setting called to mind a kind of rough-hewn logging camp, with several airy, screened-in buildings set on five-foot stilts connected by a grid of plank catwalks. Amid exuberant shouts and pounding hammers, the teams added flourishes to the training center between sessions: dining tables and benches for the refectory, racks for hanging hammocks in the dormitories, ramps down the embankment to the boats. The mood was industrious and optimistic, but also subdued.

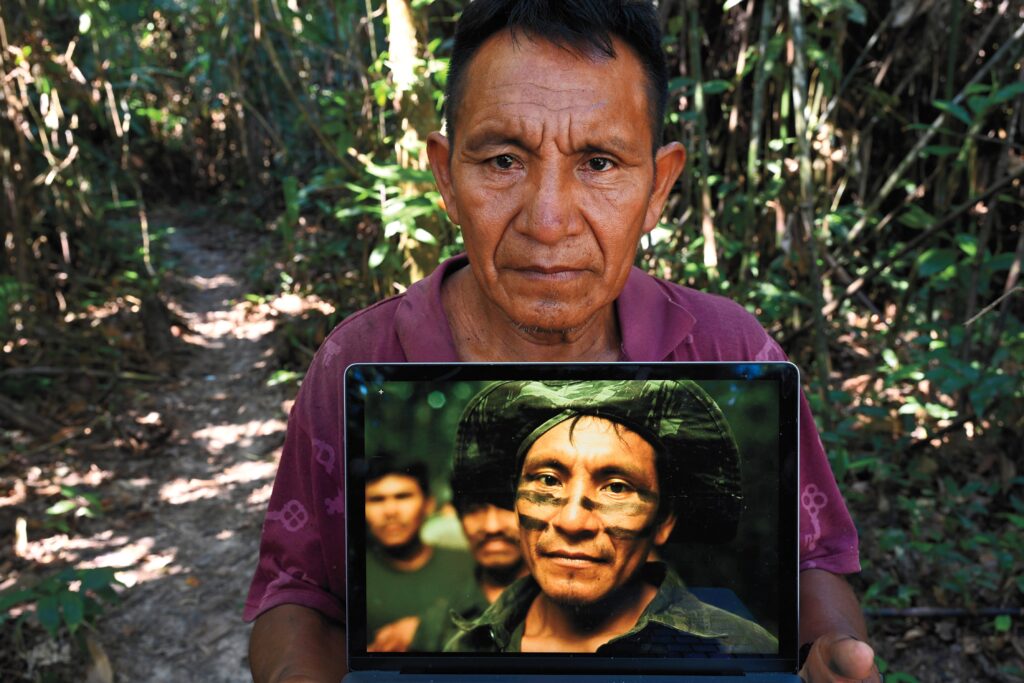

The 2022 murders of Indigenous rights activist Bruno Pereira, one of EVU’s founders, and British journalist Dom Phillips at the hands of poachers with suspected links to the drug trade were frequently invoked in sessions and private conversations. Participants were urged to avoid confronting trespassers, and instead to gather evidence and report it up the chain of command for authorities to act. “Remember, we are not a militia,” Indigenous attorney Eliesio Marubo, Beto’s brother, told the assembly. The volunteers were also warned to refrain from posting images from the event on social media that could expose them or their companions to reprisals.

Just about everyone at the meeting owned a smartphone, and they frequently communicated with friends and family back in their villages via Starlink. The availability of instant communication in the depths of the jungle was remarkable; Starlink is also present aboard all six of the organization’s patrol boats.

The paradox of using cutting-edge technology to help preserve ancient, traditional cultures and the forests that harbor them is not lost on Orlando Possuelo, one of EVU’s founders and the movement’s chief field advisor. But there’s no turning back the clock on the changes sweeping the Javari, he told me.

That includes a growing sense of agency among the Indigenous people themselves. Orlando, Sydney Possuelo’s son, worked for years as a FUNAI contractor and said the era of paternalism from FUNAI and other agencies is now a thing of the past. “In a word, it’s about autonomy … the decisions will now be theirs to make.”