RIO DE JANEIRO – Pledges made at the global Climate Summit convened by the U.S. on Earth Day — marking the welcome return of the U.S. to the efforts to address climate change — were met by many with skepticism. Headlines around the world focused on the promises made by presidents, kings and prime ministers, and whether they would actually translate into action.

But less noticed at the summit was the launch of a financial tool that could significantly help translate promises into effective initiatives when it comes to tropical forests. To be fair, there were more questions than answers around the new public-private coalition called Lowering Emissions by Accelerating Forest finance (LEAF), created with the goal to end tropical deforestation by 2030. We do know though that unlike the UN’s Reduction of Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD+) mechanism, this scheme starts already underwritten by several large multinationals and a few developed countries. And that, ultimately, this new mechanism could establish a race to the top on climate ambition, stimulating competition amongst tropical-forest nations around financial compensations for achievements in halting deforestation or increasing reforestation.

What this fund promises to deliver is immediate action. Financing options geared to environmental initiatives usually take into account a country’s track record, but LEAF looks to disburse for targets achieved by the applicant (you have to contain or reverse deforestation now and get the money next), a much stronger incentive for countries to implement initiatives and show results as fast as possible. Having cut emissions or deforestation in the past is good, but what we need is to accelerate cuts now.

The ball now is in the fund investors’ court to fund the scheme with more than the opening $1 billion and clarify if it will build on similar UN mechanisms. At the summit, Latin American leaders raised a lack of financing as a major hurdle to combat climate change and curb deforestation – the question is whether regional governments will be ready and able to benefit from this new tool.

Between Colombia’s avant-garde position and Brazil’s backwardness, Latin American nations are yet to converge on the climate race around net zero deforestation. For the Amazon region, moving away from deforestation and fires is a must, if the Amazon Basin’s dieback is to be avoided. Schemes like LEAF can help align incentives and promote long-term protection of critical ecosystems in the region. As stated by the U.S. Special Presidential Envoy on Climate John Kerry, at the launch of the LEAF Coalition, “Forests are without exaggeration one of the most important means to a net zero future.”

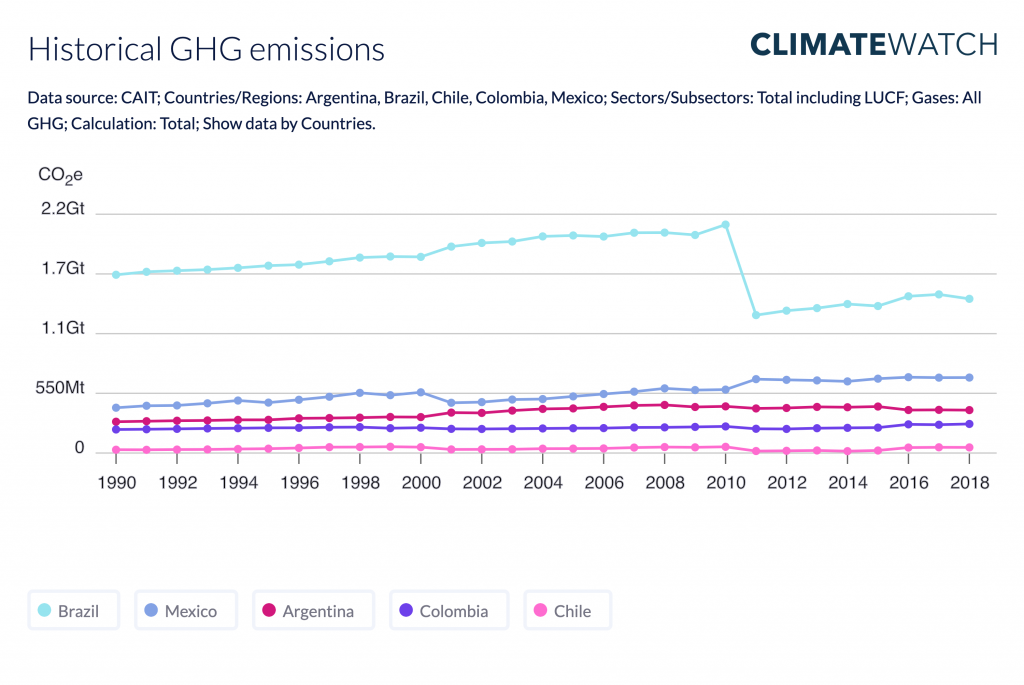

The stark differences between the five Latin American governments invited to the summit (Colombia, Chile, Argentina, Mexico and Brazil) were on full display.

Colombia’s commitment to a 51% emissions reduction target by 2030 inscribed the nation in the selected hall of countries willing to slash emissions by half during this decade. The country is also committing to reach net zero deforestation by 2030, in line with LEAF’s vision of halting and reversing deforestation. At the summit, President Iván Duque spoke about energy transition, clean transportation and the Leticia Pact to protect the Amazon rainforest, and presented possibly the most ambitious plan in the region.

Chile’s President Sebastián Piñera said the country aims to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, and become an exporter of green hydrogen. Piñera did not mention forests or terrestrial ecosystems during his statement at the summit – his focus was on the importance of protecting the ocean. However, Chile benefited already from the UN Green Climate Fund’s payments for reductions of emissions from deforestation, and its emissions in the land use sector are currently negative.

Argentina presented one of the strongest mitigation targets at the summit, even including a carbon budget for 2021-2030. It moved from conditional to unconditional pledges, meaning that it will not depend on international finance to take action. President Alberto Fernández called for eradicating illegal deforestation and improving regional cooperation, eyeing the ratification of Mercosur’s trade agreement with the European Union.

On the other hand, President Jair Bolsonaro, from Brazil, and President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), from Mexico, fell short in terms of providing political signals to stimulate a transition to a net zero carbon economy.

AMLO announced that Mexico is expanding its reforestation program, with a view to create more than 1 million jobs and plant 3 billion trees. That program, however, is not clearly related to climate change mitigation – it is a social program that promotes fruit tree-planting by small landowners. Mexico could potentially benefit from LEAF if it provides verified results on increasing forest cover. Yet it wouldn’t necessarily promote structural change because the oil sector is increasingly threatening the prospects for Mexico to become a zero-carbon economy.

Brazil was eager to establish a bilateral agreement with the U.S. on forests but concerns raised by politicians, civil society, investors and others about what kind of incentives such cooperation would provide to Bolsonaro’s government shifted the negotiations away from Brazil and toward LEAF.

Using a defensive tone at the summit, Bolsonaro asked the international community to provide a “fair payment” for the environmental services provided and results achieved by past governments, despite the current increasing deforestation rates in all of Brazil’s biomes.

Bolsonaro’s requests for payments to fund policing and military actions in the Amazon are the equivalent of telling the world that the rule of law in the country is dysfunctional. Combating speculative deforestation is already an obligation of the Brazilian State. In other words, it does not add to Brazil’s credibility, nor does it add ambition to climate policy.

In addition, Brazil did receive payments to help with environmental protection. There are currently $500 million already paid by Norway and Germany paralyzed in the Amazon Fund since 2019, as well as $96 million from the UN’s Green Climate Fund received two years ago, also unspent.

As the nation with the largest rainforest in the world, Brazil’s best chance to participate in LEAF is through state governments, which already indicated in a joint letter their intention to attract investment directly to support local initiatives towards a transition to zero emissions. However, state governors can’t control deforestation in federal lands, like indigenous territories and national parks that saw a boom in fires and degradation in recent years. That’s up to Bolsonaro’s administration – but one should not expect him to take on political costs to curb deforestation during his mandate.