GUATEMALA CITY — On Tuesday, the tension and uncertainty surrounding Guatemala’s presidential transition reached a new high. President-elect Bernardo Arévalo and his Movimiento Semilla party decided to suspend taking part in the presidential transition process ahead of the January 14 inauguration, demanding the removal or resignation of Attorney General Consuelo Porras.

The decision represents a new test for Guatemala’s authorities and institutions, as Arévalo and Semilla also filed a criminal case in the court system accusing Porras and two of her allies of violating the constitution and several other laws.

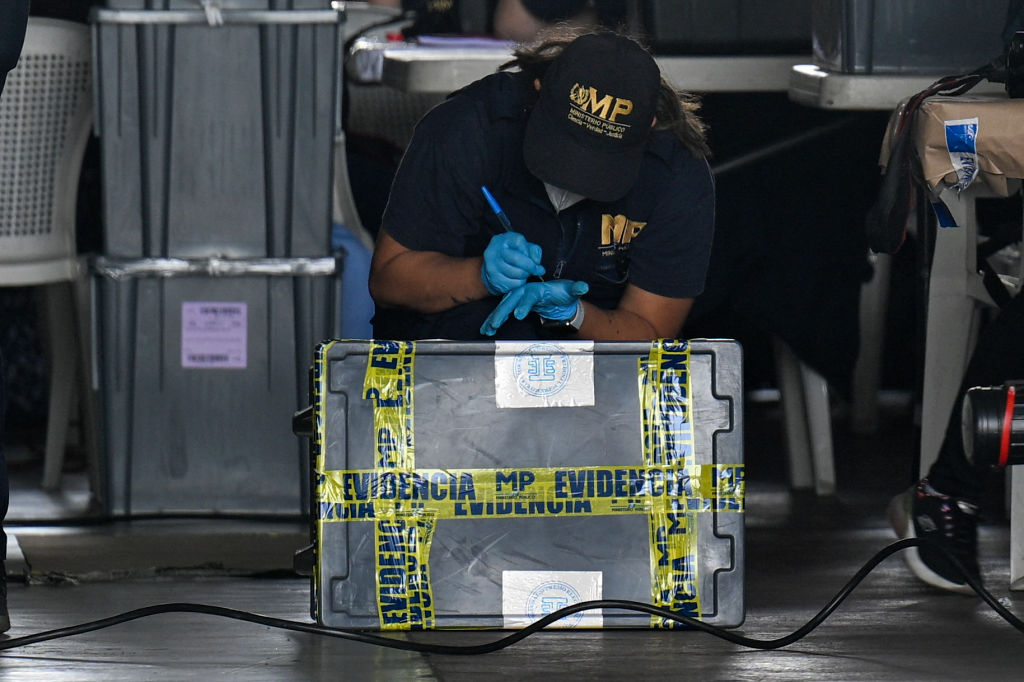

While the implications and final outcome of both moves are difficult to predict, they are taking place hours after Guatemalan investigators from Porras’ Public Ministry (PM) raided once more the offices of the country’s Supreme Elections Court (TSE). This time, they took the unprecedented step of opening sealed and certified boxes of votes from this year’s elections, undermining their legitimacy. “It was grotesque,” TSE presiding judge Irma Palencia said of the raid.

Arévalo’s reaction represents a bold decision in a confrontation with the status quo after winning the election on August 20. The president-elect has said that “a coup d’état … [is] being undertaken step by step” to overturn the decision made by Guatemalans weeks ago. As the vote continues to be disputed, Semilla remains under criminal investigation. Arévalo told me in a September 3 interview that the “coup” was being carried out not by security forces but rather by compromised judges and prosecutors, to prevent him from taking office and implementing his anti-corruption agenda.

The tumultuous presidential transition in the aftermath of Arévalo’s stunning 61-39 runoff victory shows what’s ahead. To take office and then govern, he will have to face off not simply against a rival political project, but something much broader: deeply rooted networks of corruption and privilege. His great challenge will be to begin to dismantle the networks of politicians and economic elites who have coopted high courts and prosecutors’ offices and formed pragmatic power-sharing partnerships with drug trafficking and other organized crime groups.

Photo by Johan Ordonez.

It is an uphill battle, but Arévalo and Semilla have proved adept at driving wedges into these networks. They have a great deal of public support after running a shoestring anti-corruption campaign portraying themselves as moderate and capable alternatives to a deeply unpopular status quo defined by corruption. Arévalo is also known for his talent for conciliation, which has led some business associations and other private sector leaders to support him after initially expressing skepticism.

Now, Semilla hopes that Tuesday’s raid was so egregious and so widely condemned that the party may be able to force Porras, the attorney general, from office. She was sanctioned by the U.S. for alleged corruption in 2021 and is the only individual Arévalo has singled out as a personification of the forces attempting to prevent him from taking office. Porras’ mandate as attorney general runs through May 2026, and under Guatemalan law she cannot be removed from office before then—unless she is convicted of a major crime.

Semilla’s criminal case against Porras may result in just that. It seems that Porras is running out of allies as pressure mounts. Professional organizations, student movements and powerful Indigenous grassroots groups have all rallied around Semilla, taking to the streets to defend the election results and demand Porras’ resignation. Major private sector groups that previously seemed on the fence have also recently expressed public disapproval of the PM’s election-related investigations. Meanwhile, the international community has steadfastly supported the presidential transition. The Organization of American States (OAS), for example, observed the elections and made the unprecedented decision to maintain its observation program through the transfer of power.

If Porras does leave office, it will be a major win for Arévalo. It would weaken the criminal case against Semilla, which has cast doubt on whether not only Arévalo, but also his party’s elected members of Congress, will be allowed to take office. It would also strengthen the executive branch’s ability to prosecute corruption. This is especially important because even if Arévalo and Semilla’s members of Congress do take office, they will face a hostile and obstructionist legislature dominated by status quo parties. It will be up to the executive branch to make meaningful progress on corruption, and if Porras isn’t removed, Arévalo will be saddled with an obstructionist attorney general likely to stymie any major investigation.

The case for transparency

If Porras stays, Arévalo still plans to clean up other parts of executive branch. He argues that even heavily coopted institutions can be righted because most of the state’s bureaucracy is staffed by capable civil servants who just need the right leaders. He and his camp also believe that such moves can change the political climate enough to affect other branches of government. They point to the TSE, for example, which had been systematically weakened while several of its judges had been implicated in alleged corruption schemes. After the elections, in an unexpected turnaround, it became a bulwark for democracy, thus far rejecting efforts to overturn the election results.

Within the executive branch, Arévalo plans to focus on the government contracting and permitting processes at the center of some of the most high-profile corruption investigations of the past decade. By appointing qualified people focused on transparency to key positions in the Communications and Infrastructure Ministry, for example, he believes the ministry can become a strength rather than a weakness of the Guatemalan state. He also says he’ll eliminate the widespread plazas fantasmas—lucrative government ghost sinecures that the well-connected secure for their family, friends and associates, draining government coffers and capabilities. Finally, Arévalo plans to exercise more oversight of Guatemala’s port system, a major hub for contraband trafficking and illicit dealing.

Arévalo and his team have a roadmap they believe in and broad public support; their optimism has proved contagious. But given the forces arrayed against them, it’s unclear how long this optimism will last.