This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Guatemala

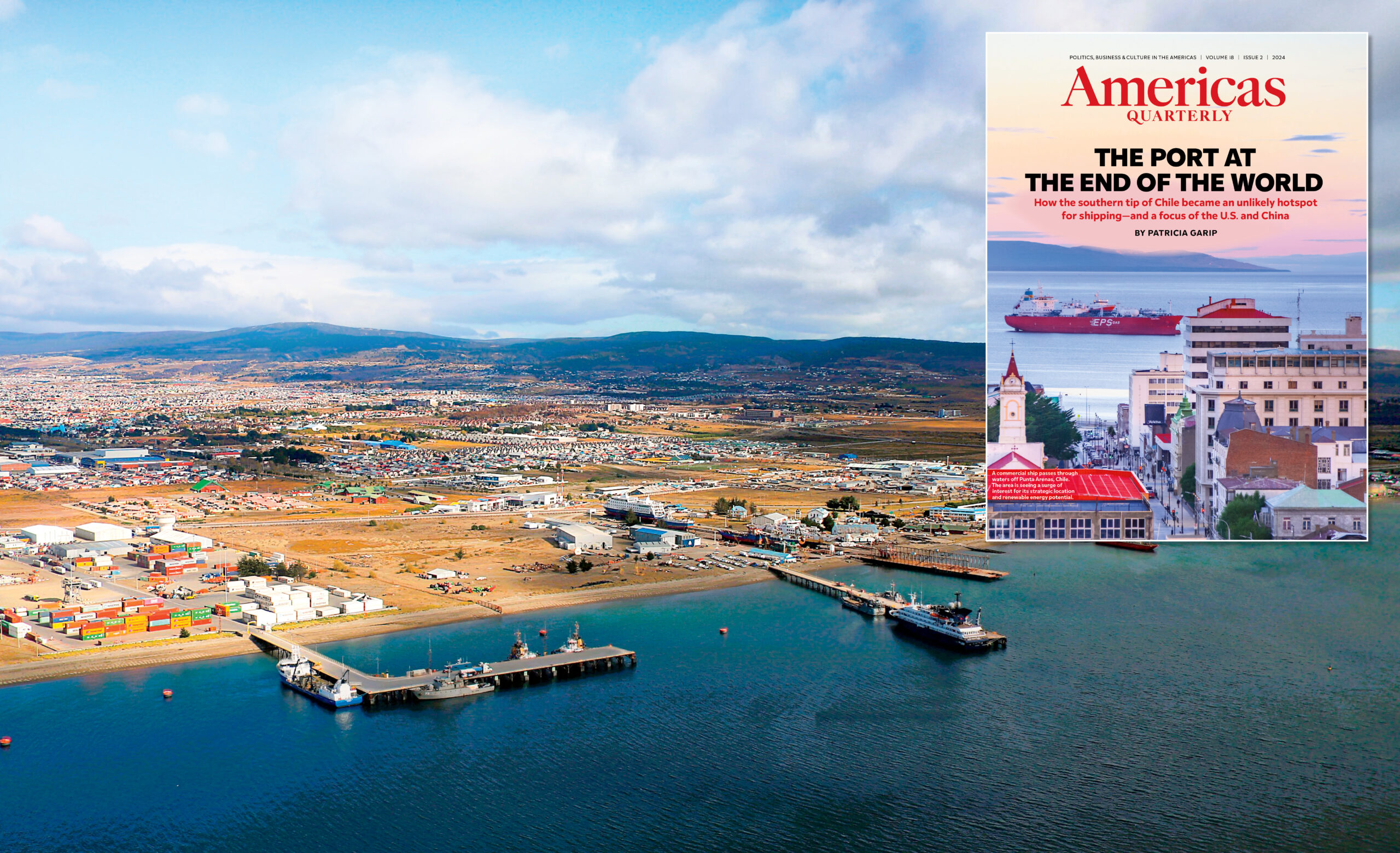

The latest postcard from the gusty shores of Punta Arenas in far southern Chile shows off the same picturesque vista as a year ago: ships, whales, a crimson sunset—and few ports.

The goal of transforming this region into a green energy hub and a major gateway to the Antarctic is behind schedule, but some local projects are now picking up steam. The process is part of Latin America’s race to develop its ports—crucial for trade, regional integration, and economic diversification—which has only accelerated since AQ published its cover story last year on port infrastructure.

This race is at the heart of the intensifying U.S.-China economic rivalry in the region, which most recently put the Panama Canal’s contested ports in the spotlight. Last November, it was China’s sprawling Chancay port in Peru drawing headlines, as President Xi Jinping himself inaugurated the new deepwater facility. This added urgency to Chile’s long-awaited $2.5 billion expansion of San Antonio, its largest port, which the country kicked off in January.

Meanwhile, port security has taken center stage in the fight against organized crime. As international law enforcement cracks down on ports known to be trafficking hotspots, cartels are increasingly seeking new routes out of “quiet” ports in countries like Costa Rica and Chile where shipments attract less scrutiny, turning them into new flash points.

All this continues to reverberate even in Chile’s remote Magallanes region. The area has attracted attention from both the U.S. and China for its geostrategic location, and over the past few years, it has seen a burst of activity as a series of major green hydrogen proposals have spurred new port plans. Some initial exuberance has worn off.

The initial crop of green hydrogen proposals has dwindled down to three or four big ones seen as viable. For this hardier group, European and Asian demand for green hydrogen products has weathered uncertainty over climate initiatives and financing conditions. Perhaps more importantly, in Chile, the public and private sectors are collaborating to streamline zoning, environmental permitting, and ground, air and sea logistics.

Not so fast

This effort is helping locally, but national barriers remain. Five years ago, proponents were bullishly projecting that Chile would export the world’s lowest-cost green hydrogen by 2030. Now, it’s more likely to kick in five years later, depending on the course of Chile’s notoriously slow permitting process, Mario Marchese, president of the trade group H2 Magallanes, told AQ. There’s broad political consensus that red tape is a chronic problem thwarting investment and economic growth, and the outgoing administration of President Gabriel Boric has sponsored legislation to help. Still, major reform has proven elusive.

In Magallanes, however, there are bright spots. Chile’s navy has expedited at least two new port concessions. “A process that historically took five years was done in less than two. There’s no better demonstration of the government’s commitment,” Marchese said. These speedy authorizations reflect the proactive posture the navy has adopted, as Admiral Jorge Castillo expressed to AQ last year.

One of these concessions, at San Gregorio, is slated to anchor HNH Energy’s $11 billion project to produce green ammonia, as well as investments from two other hydrogen developers. The other, in Gente Grande Bay, would facilitate the U.K.-based Transitional Energy Group’s plans to produce green ammonia on Tierra del Fuego Island.

A third proposed port at Posesión, near the Strait of Magellan’s Atlantic mouth, is also gaining traction. It would support France’s Total Eren as it imports equipment through Argentina and exports green ammonia. Meanwhile, three existing ports in Magallanes are expected to be retrofitted and expanded to facilitate imports of large-scale equipment such as wind turbine blades and electrolyzers.

This construction is fueled largely by Europe’s ongoing commitment to incorporating green hydrogen into its energy matrix. A shift in Europe’s spending priorities to focus on defense may pose fresh challenges, so many eyes are now on Japan. The country is holding a groundbreaking tender featuring a subsidy of up to $20 billion for low-carbon hydrogen, with a focus on a promising derivative: green ammonia. Chile is poised to capitalize if it can streamline permitting.

“Green hydrogen and its derivatives today face important international challenges that we as a country can’t control,” said Hernán Velasco, project manager of Otway Green Energy, which plans to use one of Magallanes’ retrofitted ports. On the other hand, “there are some things controlled by the state that we could advance, but unfortunately we are ever farther away from doing them. If we continue on this path, we won’t be ready to seize the opportunity.”