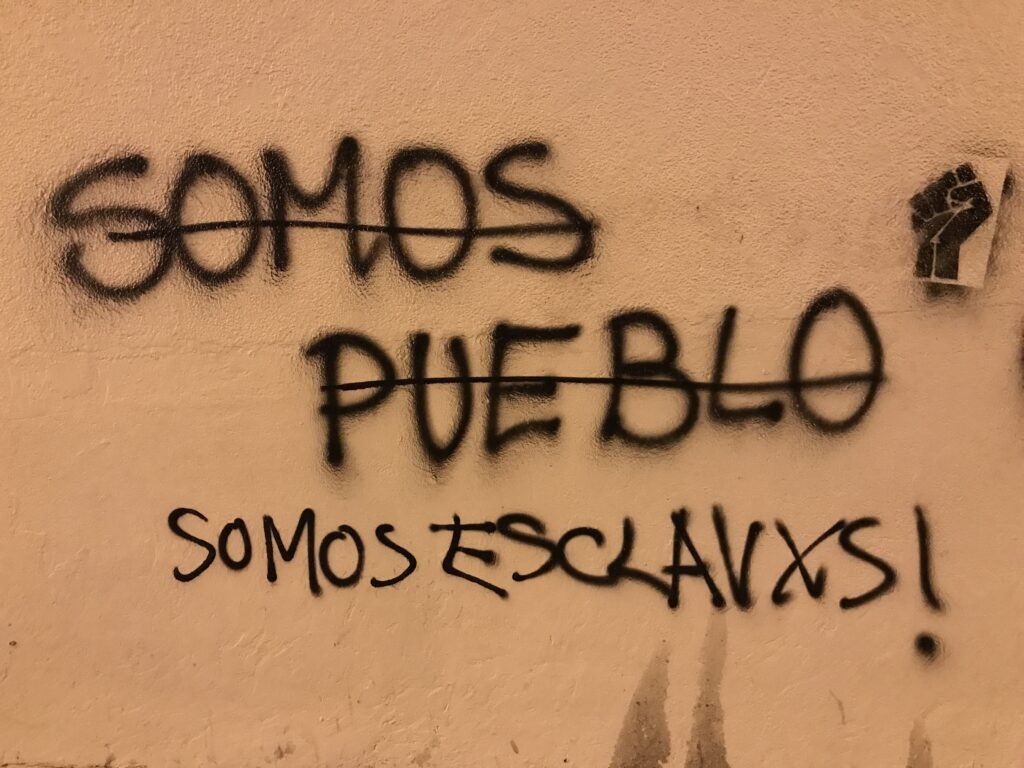

LA PAZ — The layers of graffiti on the walls of La Paz, Bolivia tell the story of the last few years. When the Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS) party returned to power in a landslide election victory in October 2020—bringing the country out of a period of crisis in the process—triumphant messages were sprayed across the city: “We’re the majority”; “We’re the people”; “Respect the wiphala”, referring to the flag of Bolivia’s Indigenous peoples and its dual national flag.

But more recently, a different message has appeared: “Estamos saliendo adelante,” or “We’re moving forward.” As the country limps out of the pandemic, those words read a little unsure—and perhaps even a little desperate.

After 10 years of hegemony from 2009 to 2019, the MAS finds itself in a new political reality: one of mere dominance. Add the distraction of infighting within the party and the very conditional support of social organizations that back it, and the MAS seems in poor shape to navigate the mounting economic challenges ahead.

The MAS has been weakened in several ways since 2019. Though the party still enjoys a majority in both chambers of parliament, it no longer has a two-thirds supermajority. It won comfortably in the national elections of 2020, but saw mixed results in sub-national elections in 2021. And where its leadership was once concentrated in the figure of former President Evo Morales, it is now dispersed between three squabbling factions.

“Evo remains an important symbolic figure, but the one who manages the resources of the state is President Luis Arce, and the symbolic power is contested by vice-president David Choquehuanca,” Roberto Laserna, director of Ceres, a think tank in Cochabamba, told AQ.

The MAS’ weakened condition has shown itself in various ways. In parliament, for example, the election of a new ombudsperson is proving difficult. Previously, with its supermajority, the MAS could choose who it wanted. Now any candidate will need cross-party support—and the opposition is refusing to go along, claiming the MAS has interfered in the selection process. On the streets, meanwhile, the government has been forced into U-turns on policies that annoyed parts of its base. And it seems unwilling or unable to confront illegal activity—such as contraband, land grabs and illegal gold mining—associated with certain sectors that support it.

“It gives the impression that this is a government unable to control these matters as a state,” María Teresa Zegada, a sociologist, told AQ. “And that is very dangerous for the country in the medium term.”

Political infighting within the MAS seems to absorb much of its attention. Elements of the Bolivian press hostile to the government might exaggerate the divisions, but they are real enough. The MAS is more divided than at any point since it came to power in 2005. A simmering war of words between rival factions recently boiled over into violence in a town in Potosí, where clashes between two groups, reported to be supporters of Choquehuanca and Morales, claimed the lives of two people. There is also already tension around who will lead the MAS into the 2025 elections. Evo 2025—another common bit of graffiti—is not guaranteed.

“I think it is probable, but it should be avoidable,” Pedro Portugal, founder of Pukara, a publication about the culture and politics of Bolivia’s Indigenous peoples, told AQ. “In Bolivia, no caudillo is untouchable or eternal.”

The internal divisions of the MAS are likely more pronounced for lack of an effective opposition to rally against. Fragmentation has been a feature of the opposition since the MAS came to power, and the crisis of 2019 did little to change this. Today, the opposition ranges from far-right leaders like Fernando Camacho, governor of Santa Cruz, to disaffected former MAS members like Eva Copa, mayor of El Alto. Such leaders have their local niches of power but lack appeal at the national level. Meanwhile, national figures like Carlos Mesa, leader of Comunidad Ciudadana, the second largest political party, lack regional reach.

“(The opposition) has some power, but it’s atomized,” Jorge Derpic, assistant professor at the University of Georgia, told AQ. “They cannot present to the national level like the MAS does.”

One way the MAS might generate some internal cohesion is through the trial of Jeanine Áñez, the former president of Bolivia, who stands accused of assuming the presidency illegally in November 2019. The trial is taking place in a context of political polarization and doubts over the impartiality of the justice system, so the opposition—and society as a whole—are unlikely to accept the outcome as legitimate. Nonetheless, it serves a political function for the MAS.

“It’s a way of showing its voters and social movements that what happened in 2019 is not going unpunished,” said Zegada.

And if Áñez is found guilty, it will reinforce the MAS narrative that a coup occurred with Morales as its victim.

“It may reinvigorate the figure of Evo,” said Derpic.

While such polarization remains the story for the political class, the general population seems more preoccupied by the threat of an economic crisis—even if the country has proven temporarily insulated from global events. The headline figures look good—CEPAL predicts GDP growth of 3.2% in 2022, while inflation in the year up to March was less than 1%—but they don’t tell the whole story. With 3.2% growth in 2022, the economy would barely return to its pre-pandemic level. Meanwhile, the low inflation is the result of government subsidies and a dollar peg that can only be sustained with a fiscal deficit for so long. The government has doubled down on its economic model, using public investment to drive internal demand—only now, that investment is increasingly debt-driven. Foreign reserves are low, and public debt is approaching 70% of GDP.

“This is a government that got used to governing with a full wallet,” said Laserna. “They no longer have the same capacity to paper over the problems with money.”

From 2005 to 2019, the MAS oversaw a period of exceptional stability and growth—not just in the history of Bolivia, but in the context of the region. It may soon face a sustained fall or stagnation in living conditions for the first time, and it’s unclear how its supporters will react.

“The vote of the people is not a guarantee of absolute and permanent loyalty for five years, nor is it a blank check,” said Laserna. “It can flip at any moment.”

—

Graham is a freelance journalist based in La Paz, Bolivia. He has reported from Europe, North Africa and South America for The Guardian, The Economist and World Politics Review, among others.