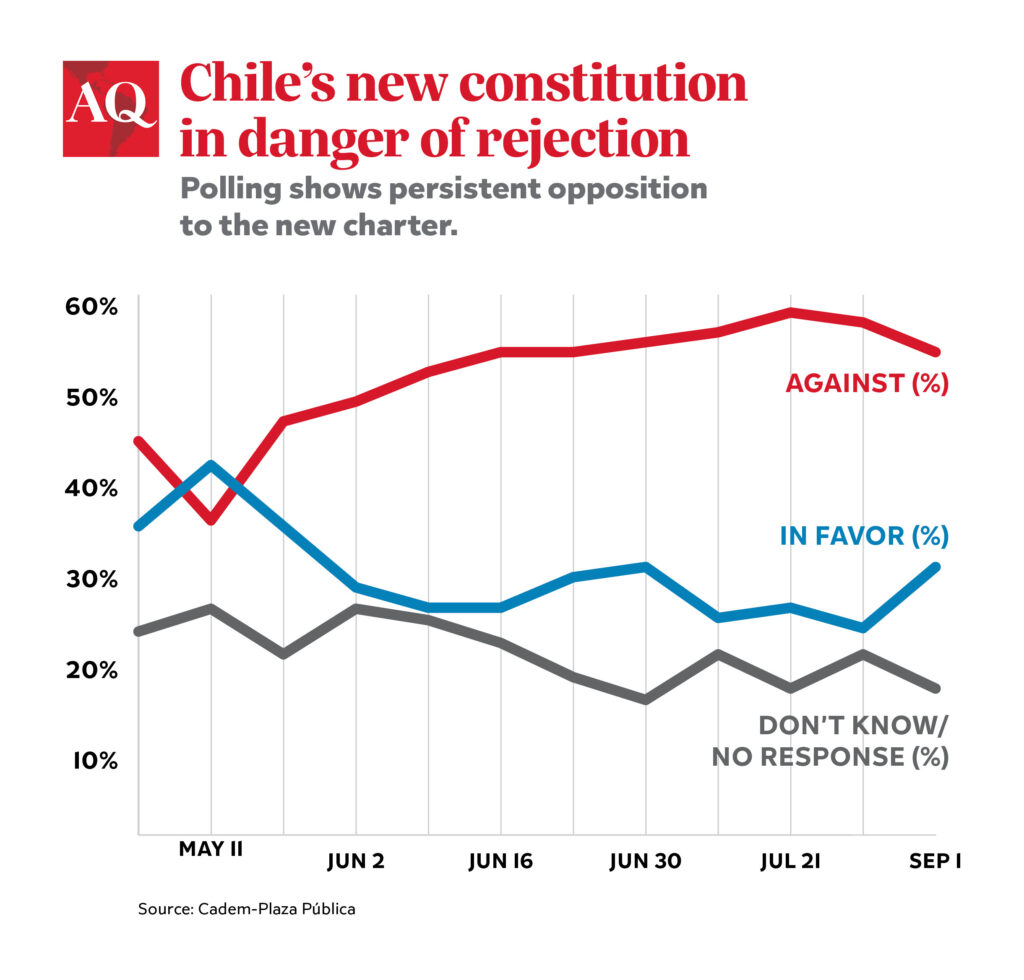

For the past six months, Chile’s constitution has been under surgery in a second attempt to recast the fundamental rights that will bring the country into the modern era. Polls show that the effort of an expert commission and the council overseeing the process is heading toward another rejection in December’s referendum. Despite recent concessions by the Partido Republicano, which has the largest representation on the council, some observers remain skeptical about whether the new text will be approved in the upcoming vote.

Last week, commissions within the council started voting on amendments to a draft drawn up by the expert commission. Initially opposed to rewriting the charter, the ultra-conservative Partido Republicano withdrew last week four of the most controversial amendments of the 400 it originally filed, including a provision raising the quorum to modify the constitution to two-thirds of Congress and a clause to “protect the life of the child about to be born.” Critics warned that the latter amendment would put at risk Chile’s law permitting abortion in three specific instances, creating additional friction in a process with a lot at stake.

The party also retracted an amendment allowing prisoners over 75 to serve the remainder of their sentences under house arrest—opponents had noted this could benefit those imprisoned for dictatorship-era human rights violations. These conciliatory gestures surprised some analysts, because the Republicanos had expressed reluctance to recraft the 1980 charter written under the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet.

Political tensions are high ahead of the 50th anniversary of the military coup, and the constitutional text must be finalized by November 7. President Gabriel Boric, who cannot run for immediate reelection, said in June that this would be the last attempt during his administration. If the text is rejected, Boric said, “I believe the conditions would not be there to carry out a new constitutional process.”

The Partido Republicano has been promoting its amendments across the country with its “¡Te quiero Chile!” campaign. “The idea is that citizens recognize the Republicano identity through our amendments,” said councilor Luis Silva, a Republicano who drew controversy in May when he described Pinochet as a “statesman.”

In a written response to questions from AQ, Silva said his party withdrew four of its amendments because “we wanted to give a very clear signal that we are willing to be flexible on our stances on amendments that, even though they are important to us, could create unnecessary noise in this process.” When asked about the new constitution’s chances in this December’s referendum, Silva added that the possibility of rejection commits the 50 councilors to “strive to propose a constitution that makes sense for the broadest possible majority of Chileans.”

Electoral implications

Improving the chances of approving the new constitution may affect the Republicanos’ future. Some analysts find that the party has used the constitutional process as a platform as its founder and most visible leader, José Antonio Kast, eyes another run at the presidency in 2025. Patricio Navia, a professor at New York University and Universidad Diego Portales, told AQ that the Republicanos “perceive that this is an opportunity for them to become the hegemonic power in the political right.”

The Partido Republicano’s conservatism has appealed to more voters in the wake of the social unrest of late 2019, the pandemic, an economic downturn, a security crisis, and the rejection of last year’s proposed constitution that struck many Chileans as too transformative and leftist. According to Universidad San Sebastián professor Kenneth Bunker, the Republicanos “were very precise and intelligent in capturing the demand for order and understanding that the country had delved so much into chaos.”

A former legislator, Kast left the right-wing party Unión Demócrata Independiente in 2016 after an internal dispute and founded the Partido Republicano in 2019. He had the highest vote share in the first round of the 2021 presidential election, but lost to Boric by 11 points in the second round.

In an election this May, the Republicanos won the most seats on the constitutional council, and a July survey from the Centro de Estudios Públicos found that while 60% of respondents don’t identify with any political party, of those who do, the highest percentage (10%) identified with the Partido Republicano. Kast and center-right mayor Evelyn Matthei currently lead polls for the 2025 presidential race.

Some analysts stress that the Republicanos’ strong electoral performance in May does not mean the Chilean electorate at large has swung to the right. Rather, that victory in part reflected dissatisfaction with the first constitutional convention and with Boric’s administration, which in the last week of August had only a 29% approval rating in a Cadem survey.

Prospects for passage

The constitution’s approval may be a long shot. According to Universidad de los Andes professor Paula Schmidt, when the process to pursue a new constitution began four years ago, “most people had high hopes and high expectations.” Today, “people are just not very positive, and they don’t see that this is going to help them improve their lives.”

Javier Couso, a professor at Universidad Diego Portales and the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands, told AQ that the Republicanos’ withdrawal of four amendments was “too little too late,” and the party has put forward other controversial amendments, such as one that constitutionally forbids property tax. Amendments require three-fifths approval in a plenary vote to be included in the final text.

Navia noted that by “promoting some amendments that are dear to their hearts and withdrawing others,” the Republicanos hope that “they will be able to propose a text that can be approved by a majority and that will still signal to their hardcore base that they have defended their conservative principles. I am a bit skeptical as to whether that strategy will work.”

Sectors on the right and the left have signaled that the path ahead remains fraught. On September 6, the center-left bloc on the council said in a statement that the Partido Republicano was seeking to “write an extreme constitution,” denounced “democratic setbacks” in the process, and called on the entire council to withdraw all proposed amendments. The right-wing bloc declined to do so.

The fate of the new constitution may also depend on messaging from Kast himself—he stated that if the Republicanos’ amendments weren’t approved, “we would have no problem saying, ‘we cannot call on people to approve this’.”