LIMA – In most countries, the arrest of a former head of state on corruption allegations would trigger uproar. In Peru, the pre-trial detention of former President Ollanta Humala and his wife Nadine Heredia has met with something of a collective shrug.

The country has been here before. Recently. Of Humala’s three predecessors spanning 1990-2011, one is in jail serving a 25-year sentence for high crimes including massive larceny of public coffers, a second is wanted on charges that he took $20 million in kickbacks, and a third is also under criminal investigation for possible graft.

The latter two’s legal travails are a direct result of the Odebrecht corruption mega-scandal, which has rocked Peru more than any other country outside of Brazil. The São Paulo-based construction giant has won public contracts totaling $25 billion here over the last three decades. It is now emerging the company curried favor through bribes and other gifts with numerous high-level functionaries to do so, allegedly including Humala, his two immediate predecessors and various other Peruvian political VIPs.

That Pandora’s box of revelations has led to the paralysis of the construction of a $7 billion gas pipeline by the Brazilian engineering firm. More broadly, the “Odebrecht effect,” including investors’ lost confidence, combined with the disastrous flooding triggered by El Niño earlier this year, is forecast to knock 1.5 percent from Peru’s 2017 GDP growth.

The mushrooming scandal has also placed Peru’s widely distrusted legal institutions in the spotlight, with many concerned that partial or weak judges and prosecutors will fail to mete out justice evenly.

Humala’s detention remains popular with the public, with 79 percent backing it, but controversial among legal experts, notwithstanding apparently strong documentary evidence against him. The leftwing firebrand turned social democrat and Heredia are accused of taking $3 million in under-the-table campaign contributions from Odebrecht in 2011 and an undisclosed sum from Venezuela in 2006.

The judge in the case was concerned that the pair would meddle with evidence had they remained free. Audio tapes of Humala’s inner circle recently published by Peruvian media appear to confirm that he bought off witnesses in a separate case, in which he was accused of ordering extrajudicial executions while serving as an army captain at a remote base in the Amazon in the 1990s. Heredia is also accused of faking a handwriting sample.

“The detention strikes me as polemical because Humala always attended every court hearing he was cited for and made no attempt to leave the country,” Heber Joel Campos, a professor of constitutional law at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, told AQ.

Humala’s arrest comes as Alejandro Toledo, centrist president from 2001 to 2006, fights extradition from his home in California, accused of charging Odebrecht kickbacks for approving its bid to build sections of the Interoceanic Highway, cutting through the Amazon and over the Andes to the Pacific.

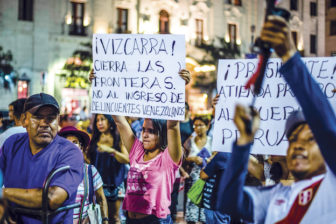

The big question now is whether prosecutors show the same energy in their pursuit of the two principal political rivals of Toledo and Humala, in particular Alan García, who was president between the pair, and Keiko Fujimori, who was presidential runner up in 2011 and 2016 and now leads the largest party in Peru’s congress.

According to testimony from Marcelo Odebrecht, the jailed head of the eponymous construction giant, his company gave cash to all major political candidates in Peru including Fujimori and García. Despite that, Peruvian prosecutors are reported to have shown little interest in questioning Odebrecht further.

Both Fujimori and García have form in the corruption stakes.

Fujimori is the daughter of Alberto Fujimori, the jailed 1990s president whose hard-right regime ended in ignominy amid allegations of kleptocracy, death squads and vote-rigging. Her own murky personal and campaign finances have long been the subject of many unresolved questions.

García’s first disastrous presidency in the 1980s ended in hyperinflation and numerous graft scandals while his second, from 2006 to 2011, was marred by the narco-pardons case in which presidential reprieves were sold to hundreds of convicted drug traffickers. Several of García’s aides were jailed but prosecutors ruled the president had not been involved – a decision met with widespread skepticism.

He also brought down the curtain on that second period in office by building a 120-ft polyester resin imitation of Rio’s Christ the Redeemer statue with a public donation from Odebrecht as a thank you to him for awarding the company $2 billion of business.

The judiciary is regarded as Peru’s most rotten institution, while many here view prosecutors as highly partial. The political parties of Toledo and Humala have both collapsed, with not a single member of Congress between them. That makes them far more vulnerable than Fujimori, who wields a majority in the single-chamber legislature, or García, whose networking throughout the legal system is legendary.

Yet one person who believes prosecutors need space to carry out their work is José Ugaz, the Peruvian lawyer who helped bring down Alberto Fujimori and now heads Transparency International. “I don’t believe there is a political motive there,” Ugaz said of prosecutors’ work so far.

Peruvians can only hope he’s right.

—

Tegel is a journalist based in Lima, Peru