With contributing research from Miryam Hazán and Carlos López Portillo Maltos of Mexicans and Americans Thinking Together (MATT).

Read a sidebar on Mexicans and Americans Thinking Together (MATT’s) electronic job bank.

Read a sidebar on Mexican migrants’ return to restaurant work.

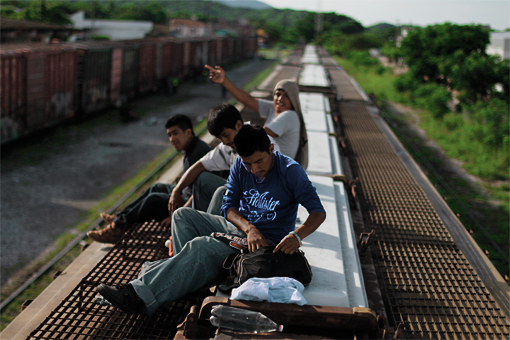

José Antonio Pérez remembers as a child seeing migrants climbing onto La Bestia (“The Beast”), the train that carries Central American migrants north to the state of Oaxaca, and wondering where they were going. An uncle told him the migrants were “traveling to El Norte,” the United States.

“I didn’t understand,” Pérez recalled. “I only understood when I was older.”

At the age of 14, he joined them. He left his hometown of Arriaga, Chiapas, in 2003 and found work in a greenhouse in Chestertown, Virginia.

Six years later, after struggling to find stable work in Virginia, he was home again. Now 24, he has found work helping out at local farms. But, unable to match the paychecks he received while working in the U.S., Pérez decided to make the journey north once more. This time, he wasn’t as lucky. In 16 attempts to cross the border over the past two years, he was stopped or detained every time. He hasn’t given up. Noting the differences in wages between Chestertown and Arriaga, Pérez is contemplating trying to cross into the U.S. again.

“We’ll see, but I think I’ll go. It’s more comfortable there,” he says.

View a slideshow of return migrants in southern Mexico.

In Mexico City, a very different dynamic is emerging. Walk into the offices of Teletech, one of the growing number of firms in the capital involved in business process outsourcing (BPO), and you will see rows of young people seated at computer workstations dressed in chic capitalino clothes or baggy California hip-hop gear. They handle tech support and social media for a variety of retail and telecommunications clients. About 40 percent of the office’s employees are returned migrants who previously worked in the United States.

One of them is Liz Barron, a 23-year-old whose parents migrated to Colorado when she was a toddler. Barron, who returned to Mexico City after high school to study psychology, now works at Teletech as a quality analyst. Like most of the return migrants at Teletech, she attended a U.S. high school but was discouraged by the high cost of pursuing a university education there. She hasn’t returned to visit her family in the U.S. and now plans to build a career in Mexico.

“It’s a place with many opportunities to grow,” she said, speaking of Teletech—but her words also describe Mexico’s growing industrial and information technology sectors.

A decade ago, Mexico barely registered as a location for information technology (IT), call centers or other customer service-related sectors. But by 2012, more than 4,000 BPO-related businesses were operating in Mexico, combining to create a nearly $6 billion sector. This sector now employs more than 625,000 people, and serves both as a draw for return migrants and as an alternative for those who might once have considered migrating.

“What we offer is so much more than just agents handling calls,” Teletech manager Ivana Jovic explained. “We provide customer care solutions. This didn’t exist 10 years ago.”

A New Migration Phenomenon: What We Don’t Know

José Antonio Pérez and Liz Barron represent two very different faces of a singular phenomenon: a return migration flow that has completely altered previously conceived notions of migration patterns.

Migration between Mexico and the U.S. has historically been cyclical, with emigrants returning home periodically after a decade, a year, or even a single harvesting season. Over the past few years, however, a combination of factors has radically shifted this dynamic. Economic transformation and growth have created new job opportunities in manufacturing, services and IT in Mexico; and population growth has slowed, diminishing the need for out-migration as a “pressure valve” for excess workers in the Mexican labor market.

Furthermore, a growing U.S. focus on border security has created new difficulties for migrants who attempt to cross the border. Between 2005 and 2012, the Department of Homeland Security’s Customs and Border Protection (CBP) budget increased by approximately $5.4 billion (an increase of 85 percent).1 Increased focus on enforcement within the U.S. has also created a deterrent, with a record number of people—nearly 2 million—deported under the Obama administration. In 2011, the U.S. repatriated more than 350,000 Mexican migrants.2

Between 2005 and 2010 only 1.4 million Mexican migrants moved north, a figure that represents less than half of the total tallied a decade earlier, between 1995 and 2000.

At the same time, southbound flows have accelerated, with hundreds of thousands of migrants returning home each year. During the same period of 2005 to 2010, 1.4 million Mexicans and their children moved in the other direction, about double those who made the move a decade before.3 Today, migration between Mexico and the U.S. is—for the first time—at net zero.

Why are migrants returning home at record rates?

A study by the Pew Hispanic Center shows that those forcibly returned only account for between 5 percent and 35 percent of people who returned from the U.S. to Mexico between 2005 and 2010, while the rest—between 65 and 95 percent—came home voluntarily.4 Similarly, surveys conducted by Mexicans and Americans Thinking Together (MATT) in the states of Hidalgo, Jalisco and Coahuila found that only—on average—about 15 percent of those interviewed were forcibly returned.

It’s clear that the majority of migrants returning home are doing so voluntarily. But information on who they are, what skills they possess, and where they are going has yet to be captured in any kind of comprehensive way.

What we do know, however, is somewhat surprising.

MATT’s survey of 600 migrants who returned to the state of Jalisco shows that 42.6 percent cited family reasons—such as homesickness or needing to take care of a family member—as the primary cause for returning. It is not surprising, then, that the states receiving the largest number of return migrants are traditional sending states. However, this may be changing. Migrants are returning at higher rates to states that in the past had low levels of out-migration, such as Baja California Norte, Baja California Sur, Sonora, Quintana Roo, and Veracruz.5

While in many cases Mexicans and Mexican Americans are returning for reasons of education and work, Liz Barron—and others like her working in the tech sector in Mexico City—may be the exception to the rule. Although between 2000 and 2010 the number of call centers in Mexico has doubled, the country’s economic growth has not been uniform, and opportunities in the BPO/IT sector are not open to all return migrants.

A study by Fundación BBVA Bancomer shows that most migrants moving back from the U.S. are more like José Pérez from Chiapas. The study suggests that the majority of those who return are young (between the ages of 18 and 34), overwhelmingly male (although the proportion of women coming back is increasing), and have low levels of education. As of 2012, 39 percent had a high school education, and 35.6 percent had secondary school or less.6

Happy Homecoming?

Despite Mexico’s quick recovery from the 2008 global financial crisis—GDP growth was 5.5 percent at the end of 2010—many rural pockets of the south have not fully integrated into the globalized economy.

Return migrants—many of whom choose to return to either their community of origin or the community where they most recently lived—do not have much to come home to, and are facing real challenges as they try to reintegrate, both economically and socially.

For migrants who failed to learn English or to enhance their long-term earning potential during their time in the U.S., job prospects tend to be scarce. And although their courage in moving north is often recognized, many complain that they are seen as failures for coming back.

This is not to say that migrants are not finding jobs at all. According to Fundación BBVA Bancomer, 70 percent of working-age return migrants find jobs within three months of their return (and 95 percent in a year or less).

But is the work they find the best use of their skills and of their time spent in El Norte? Most return migrants find work outside of the sectors where they were employed in the United States. While many of them worked, for example, in the construction and service industries in the U.S., close to 40 percent end up returning home to work in the agricultural sector.7 This suggests that while they do find employment, many are not able to take advantage of the technical skills and experiences they acquired while in the U.S.—which represents not only a loss for them, but for the Mexican economy overall.

In contrast, Mexico City and other industrial hubs in the center and north of the country have developed new industries such as manufacturing, services and IT that help provide return migrants who have acquired strong English language skills with a smoother transition into the labor market upon their return. Mexico City in particular has gone through a profound period of development, and emerged as a new magnet for return migrants, rural residents and local college graduates.

Jill Anderson, a Mexico City–based return migration scholar who has conducted extensive research on the call centers, explained that in Mexico, the IT outsourcing industry is assigning value to returned migrants’ skills.

“These are young people who are adept with technology [and are] bicultural, bilingual,” she said.

In most cases, the call center employees are individuals with a strong connection to U.S. culture, often having moved to the U.S. as children and attended schools north of the border while their parents worked.

Sitting at a table in front of the Starbucks a few blocks from Teletech, Raúl Iglesias, a 21-year-old college student (and a former Teletech employee) who returned to his home in Mexico City after spending most of middle school and high school in the suburbs of Atlanta, explained in English, “I moved there when I was 13 and came back when I was 18.”

He moved back to Mexico to attend college at Mexico’s best public university. Switching to Spanish, he explained that he attended a private high school in Mexico City for one year to avoid trouble with his school documents from the United States.

“I would have had to repeat all of high school,” he said.

Return migrants like Iglesias who come back with the ability to speak English have a clear advantage in the labor market. Unfortunately, many of the potential benefits of spending time in the U.S. can be erased if return migrants fail to successfully re-integrate into Mexico’s school system.

About 300,000 U.S.-born children of Mexican immigrants moved back to Mexico between 2005 and 2010. Many of these youth encounter problems when they try to enroll again in school. “The problem is that many students have issues with their documents,” said Guadalupe Chipole Ibáñez, a migrant outreach coordinator from Mexico’s Ministry of Rural Development. “[The Ministry] says their studies aren’t valid. Many encounter problems and stop studying.”

Sergio Aquino, the vice minister of migrant outreach in Chiapas, noted that they are making a concerted effort to help return migrants reintegrate into the school system.

“Returning migrants have a right to education, just like anyone else,” he said. “If they have documents from the U.S., we help them translate and accompany them to the civil registry. We help them find the right local school to attend. From there, they just go to school like any other person.”

For many individuals, however, the process is not quite that simple. In Chiapas and other states in Mexico, many migrants struggle to procure documents from the U.S. to meet the requirements of the Secretaría de Educación Publica (Ministry of Public Education—SEP).

The Ministry of Public Education’s complicated, strict and overly bureaucratic process used to regulate matriculation into the public school system is a major obstacle for many young return migrants, and many activists working with return migrants are frustrated.

“The SEP creates obstacles,” said migration expert Jill Anderson. “Right now, there’s no office there to support returning migrants.”

Improving the process of reintegrating young migrants into public schools and introducing them to the labor market is a huge opportunity, if Mexico can execute.

“People [in Mexico] are just waking up to the fact that there are all these young bilingual people and that this is an asset,” Anderson said.

A Challenge, But an Opportunity: Somos Mexicanos

This is a unique moment for Mexico. There is a complex challenge, but also a significant opportunity to reintegrate a diverse, talented population returning from the U.S. at a moment when, for the first time, Mexico is experiencing demographic shifts in its favor.

As families have become smaller, the number of young dependents relative to the number of working adults has declined, producing what is known as a “demographic dividend.”

Typically, when this happens, economic development accelerates; but previously Mexico was not able to leverage this change because so much of its working-age population was migrating north. With waves of people coming home, the equation has changed.

Will Mexico take advantage of this opportunity?

Policymakers, the private sector and the public school system are just starting to come to terms with the impact of return migration on their country’s society and economy.

In Chiapas, recognizing the limited economic opportunities in the state, the government has taken steps to help reintegrate this incoming population. Aquino explained that in Chiapas, various ministries, including the ministries of labor, economy, public education, and agriculture, have programs to help re-integrate migrants. The Migrant Outreach office helps migrants gain access to these programs.

At the state level, “We work in two areas: attention to migrants and the prevention of migration,” said Aquino. “We also have a business incubator program and training initiatives in tourism and restaurant management.”

Overall, though, Chiapas’ economy still provides few of the opportunities for cash income that migrant laborers find north of the border.

At the national level, what can the Mexican federal government do to play a more active role to help return migrants re-integrate into Mexico’s economy and community life?

Until very recently, the government did not have any plan in place to re-integrate this population, despite the fact that migrants have been returning from the U.S. for over 70 years. As Miryam Hazán, who conducted MATT’s survey of return migrants, put it, “Mexico had a policy of no policy.”

This is changing. On March 26, 2014, the Mexican government launched its first official program addressing the re-integration of return migrants. Although the details of how this program will function are still fuzzy, and a budget has yet to be determined, this is a significant forward step.

The new program, Somos Mexicanos, will coordinate among all relevant stakeholders in the reintegration process, including national and international NGOs, the private sector and a host of government agencies.

The effort—as proposed—will give migrants access to identification documents by issuing birth certificates in the nine repatriation centers along the U.S-Mexico border and in Mexico City. It will also give return migrants access to Mexico’s health program Seguro Popular, which offers health benefits through the Ministry of Public Health to the millions of people working in Mexico’s informal economy.

The first national effort to help return migrants find jobs, Somos Mexicanos will also provide migrants access to a web-based platform that will serve as a job bank to match them with potential employers. This job bank—developed by MATT and currently being used to connect 4,000 migrants with employers around the country—has the potential not only to systematically record the background and skillset of migrants returning from the U.S., but also link employers with these returning potential employees in a coordinated, organized way.

The plan also promises to offer migrants free certification for qualifications they may have acquired in the U.S. labor market. It will offer re-training in some key industries (that have yet to be determined), and give migrants information on opportunities to invest in their own businesses through developing and distributing a catalog of investment opportunities by locality, focusing on places with high rates of return.

If Somos Mexicanos is able to leverage current loan and investment programs for return migrants, such as the Ministry of Finance’s Migrant Support Fund (a $15.5 million dollar federal grant program that, among other things, provides seed capital to returning migrants aspiring to open a business) and provide additional support and training such as financial literacy, this could be a significant driver of economic growth. MATT’s survey in Jalisco found that 20 percent of those interviewed had invested in some way—either in a small business or buying property—using their own money.

It’s an ambitious plan. The government has yet to determine which agencies would implement different pieces of the program, and how they would coordinate. As a start, the National Population Registry must fulfill its promise to harmonize the formats used by the civil registries of all the Mexican states so that birth certificates can be issued in the repatriation centers.

But the effort would apply only to migrants who returned through repatriation centers—a minority of all migrants returning to Mexico. It is also the population most likely to leave again, although this might be changing. According to the Pew Hispanic Center, 60 percent of Mexican deportees in 2010 intended to return to the U.S. within a week, compared to 80 percent between 2005 and 2008.8

Despite the challenges, this program is a historic move in the right direction, and shows that the government is committed to this issue. Having announced last year in the Plan Nacional del Desarrollo (National Development Plan) for 2014–2018 that it would create a directive to address the reintegration of return migrants, the government has already started to deliver.9 In addition to Somos Mexicanos, the Programa Especial de Migración (Special Migration Program) 2014–2018 was launched in April, and it mandates a more coordinated effort on the part of the Mexican state to address return migration.

Whether this level of coordination—either through the Instituto Nacional de Migración (National Institute of Migration) or an independent commission—is possible remains to be seen. Its success will hinge on the political will and engagement of state and local governments, as well as the private sector.

What we do know is that this is a huge opportunity for Mexico’s economy and social fabric and for the hundreds of thousands of Mexicans who have moved back, and will follow. Whether they are English-speaking high school or college grads, construction or service-sector workers, or potential entrepreneurs, Mexico’s commitment to this population will determine its economic competitiveness and national vitality in the future.

Click here to read “Nancy Pérez: Evolution of Migrant Rights” by Nancy Pérez García.

Click here to read an article about return migrants in Guatemala by Michael McDonald.