In April 14, Venezuelans turned out en masse for a special presidential election. More than 79 percent of the electorate voted to fill the 2013–2019 term left vacant by Hugo Chávez’ March 5 death from cancer. The photo-finish surprised and captivated the country, with interim President Nicolás Maduro defeating opposition Governor Henrique Capriles by a slim margin, 1.5 percent, or around 220,000 votes.

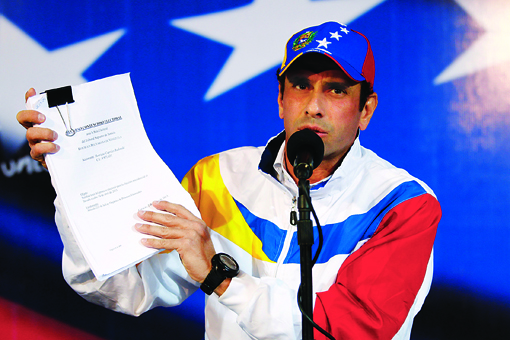

Capriles reacted by demanding first a recount and then filing a claim to nullify the elections—a sharp contrast to his acceptance of his 11-point loss to Chávez in the October 2012 election.

The events raised two questions: the first over Chávez’ seemingly (and unexpectedly) weak legacy to Venezuela’s electoral politics; the second over whether the opposition’s rejection of the electoral results—and by implication, the system—is likely to become an enduring feature of their political strategy.

Since he rode the wave of emotional support created by Chávez’ 14 years of governing, Maduro was expected to coast to victory in the snap elections. Moreover, analysts expected chavismo without Chávez to continue to dominate the political agenda, at least in the short-to-medium term. The shrinkage in the chavista vote and the rise in the opposition vote not only exposed the complex governability challenge Maduro inherited; they also suggest the Chávez legacy may be surprisingly fragile.

Two political factors underlie the electoral crisis: a distrust of government institutions borne of more than a decade of political polarization and government control, and refusal of both sides to recognize the political legitimacy of the other. The first factor erected barriers to transparency and communication; the second factor appeared to close the door to overcoming those barriers. Yet, not all the scenarios are bleak.

Venezuela’s Electoral System: Complexity and Suspicion

Maduro’s candidacy began with a constitutional controversy. After winning the October 2012 election for a third presidential term (2013-19), Chávez returned to Cuba on December 8 for further surgery; and he never appeared in public again. On January 9, 2013, one day before the constitutionally established date for the start of the new term, the Supreme Court made a controversial ruling allowing Chávez’ new term to continue from the previous one without a formal inauguration. The decision permitted the vice president to be named interim president when the 58-year old Chávez passed away on March 5, 2013.1 Maduro received the presidential sash on March 8, and the Consejo Nacional Electoral (National Electoral Council—CNE) announced April 14, 2013, as the date for the constitutionally required special election.

Maduro was thus able to campaign as president, using presidential authority to obligate television and radio coverage of presidential speeches (cadenas) and to inaugurate public works. The opposition said this gave Maduro an unfair advantage, adding to the ventajismo (abuse of incumbent advantage) they experienced in the prior campaign against Chávez. Most polls predicted a Maduro victory of 7 to 11 points. Yet at 11:15 p.m. on April 14, the five rectors of the CNE declared Maduro elected with 7,505,338 (50.66 percent) votes to Capriles’s 7,270,403 (49.07 percent), with 99.12 percent of the votes tabulated.2

Prior to announcing the results, the CNE rectors talked with each candidate, as is their normal practice. The Capriles campaign’s quick count indicated Capriles was winning, but the results fell within the margin of error, meaning the count could not definitively determine the outcome.

Nevertheless, Capriles indicated to the CNE that his numbers and the irregularities his campaign had collected from voters and pollwatchers throughout the day could add up to a different result. To reassure voters about the results, therefore, opposition-affiliated Rector Vicente Diaz suggested that the CNE expand the verification process, in which electronic tallies are compared with the paper voting receipts, from 53 percent of polling tables, to 100 percent of them.

Maduro gave a mixed-message victory speech, sprinkling in conciliatory language while sounding an overall confrontational note. He also welcomed the opposition’s request for an audit. Capriles followed, refusing to recognize the results until each ballot box of paper receipts was opened and every vote counted. The next day, the CNE formally proclaimed Maduro the winner, over the protest of the Capriles campaign. That same day, tensions boiled over with skirmishes that claimed nine lives and injured 78.3

The Venezuelan election authorities stopped inviting international election observer missions after the 2006 presidential elections. Instead, they invited individuals to “accompany” the elections in a program organized and paid for by the CNE, and invited the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) and the Inter-American Union of Electoral Organizations (UNIORE) to send “accompaniment missions.” The UNASUR head of mission explained its purpose was to share electoral experiences among its members, rather than provide a comprehensive evaluation of the elections or mediate disputes.4

From afar, international reactions to the results were swift. The day after the election, the electoral accompaniment mission of unasur endorsed the results but offered no public report.4 uniore’s first press release endorsed the results; its second offered implied criticism regarding some of the voting day conditions.5 Governments throughout Latin America and the Caribbean followed suit and recognized the Maduro victory after his proclamation on Monday, April 15. In contrast, Secretary General José Miguel Insulza of the Organization of American States (OAS) called for an audit and full vote recount and offered OAS assistance to carry it out.6 The U.S. called for a full recount of the vote and, along with Canada and initially Spain, refrained from congratulating Maduro.

Over the next two weeks, Capriles shifted his message from his early refusal to recognize the results until “every vote is counted,” to an outright accusation of fraud, saying the Maduro camp “robbed” the election.

The Debate over the Meaning of “Recount” and “Audit”

Semantics surrounding Venezuela’s automated voting system, the intricacies of its electoral law, and imprecise communication from Capriles and international actors made for a very fuzzy discussion about the audit/recount.

In Venezuela, citizens vote on touch screen voting machines and receive a paper receipt to confirm their electronic vote. They deposit the slip in a ballot box to be available for a “citizen verification,” or audit, of the electronic vote, where the paper receipts are counted and compared with the electronic tally in slightly more than half the voting tables after the close of the polls on election night. The legal vote is the one registered in the voting machine and printed out from the machine, with copies going to the central election headquarters, the election workers at that voting table, and all of the party witnesses present. The paper receipts are simply a means for the voter to confirm his/her vote, but do not play a role in the legal vote count.

While Capriles alternated between the terms “audit” and “recount,” the international press and the U.S. government used the term “recount.” They all referred to counting the votes one by one, without specifying that they really meant simply auditing the paper receipts to confirm the official tally. The CNE and Supreme Court chief rejected calls for a “recount,” explaining that in legal terms a recount (of the electronic vote) could only be ordered by the Supreme Court in response to a formal complaint, and that counting the paper receipts is simply a technical audit to help reassure voters the machines worked.

Though Capriles initially called for a “vote-by-vote recount” on April 16, which would involve opening all the ballot boxes of paper receipts, he additionally demanded examination of the printed voter lists signed and thumb printed by each voter after they vote. The formal written requests of the campaign, however, were more precise than Capriles’ somewhat confusing verbal comments, and on April 17 the campaign formally requested an “audit” of the entire system, including the various components of the automated system and the voter rolls.

On April 18, the CNE agreed to the original request made by Rector Diaz and repeated by Capriles on election night—to amplify the citizen verification process (comparing the paper receipts with the official tally from each voting machine) to 100 percent of the voting tables.8 CNE President Tibisay Lucena emphasized this was not a vote recount, but a technical audit undertaken to preserve harmony among Venezuelans. Capriles immediately accepted the CNE proposal, claiming the amplification of the audit to review 12,000 new voting tables would identify “the problems” with the voting process.

The agreement over the audit unraveled the next week, however. On April 22, the Capriles campaign submitted a more detailed written request that included the voting materials the campaign wanted to review and reiterated the components of their requested audit, including a review of the registers of the voter identification fingerprint machines and the manual voter logs to check their concerns about impersonation of voters.

The CNE did not respond to these requests and stuck to the April 18 proposal: an expanded audit of the citizen’s verification exercise that had begun on election night. Capriles rejected this procedure and the opposition did not participate in the audit that finally began May 6. As happened in previous elections when the CNE conducted the citizen verification’s audit, the count of the paper receipts confirmed the electronic results in that audit.

The Capriles campaign then pursued legal avenues. It submitted two formal petitions to the Supreme Court, the first on May 2 to annul the entire election, and the second on May 7 with more specific evidence requesting to annul the election in 5,729 of the 39,018 voting tables.9

Complaints from the opposition Mesa de la Unidad Democrática (Unity Democratic Front—MUD) about the quality of voting on election day included the ousting of opposition party witnesses from 2 percent of voting centers, government campaigning near voting centers, and intimidation of voters by government-affiliated motorcycle gangs.10 These are serious charges, though it is difficult to measure their impact on the vote count. Finally, complaints filed before the election pertaining to the competitiveness of the election, such as unequal campaign financial resources and media access, were also included in the formal complaints to the Supreme Court.

The independent report of an accredited national observer group, Observación Electoral Venezolano (Electoral Observation Venezuela—OEV) endorsed the overall efficiency of the vote while signaling that both parties committed violations on election day. For the majority of infractions it reported on, the oev found pro-Maduro compaign personnel involved more frequently than Capriles campaign personnel.11

Parsing the Chávez Legacy

The political upshot of the election crisis and the tight results is that Maduro’s presidency began without a post-election honeymoon. Capriles’ rejection of the legitimacy of the government compounded Maduro’s problems of having to face questions about his authority within chavismo after the close election results. Though many voters indicated in public opinion polls they would follow Chávez’ instructions and support Maduro, even if they weren’t enamored of him, tracking polls showed his support declining in the days leading up to the election.

Nationally, Maduro received 604,881 fewer votes than Chávez, while Capriles increased his vote share by 770,208.

The loss triggered fears of a witchhunt. On May 17, Maduro claimed to have the names and ID numbers of 900,000 chavistas who did not vote for him. The claim implied the CNE shared information about who had voted with the government, since the opposition did not have similar information. The threat also raised the specter of potential recrimination, based on a 2004 experience of denying government benefits and jobs to signers of the recall referendum petition. But at the same time, it caused the opposition to rush to reassure voters that the vote is secret, for fear that Maduro’s words would intimidate voters from participating in the future.

The close vote responds to at least two dynamics—the campaign and the political loyalty Venezuelans feel toward chavismo without Chávez. Maduro’s lackluster performance on the campaign trail, food shortages and the devaluation of the bolívar (Venezuela’s currency) when petroleum was at over $100 per barrel, and Capriles’ well-executed campaign strategy of attacking Maduro as the un-Chávez, shifted momentum in favor of the opposition.

More important are the exposed vulnerabilities regarding political loyalty to chavismo without Chávez. It is too soon to assess the extent to which lasting changes in political culture and consciousness have occurred, though Maduro’s support so far draws from Chávez’ broader political legacy. Now the movement must learn how to translate the respect and trust a majority of Venezuelans felt toward Chávez personally into genuine political identification with his party.

Maduro faces not only serious economic constraints and the strongest political opposition since 2002, but also competing and incompatible demands from within his movement. Lacking the force of personality of his predecessor, he must develop a cohesive collective leadership. The initial messages in the month after the election pointed toward political radicalization, in terms of attacking the opposition, and economic moderation, in terms of elevating less ideological individuals within the economic cabinet and reaching out to some private entrepreneurs. But he had not yet reached out to his base, which yearned for signals of a commitment to deepening the communal state, and the government made serious missteps with controversial arrests of dissidents, threatened recrimination against voters, and unseemly violence in the National Assembly.

The Challenges to Come

Chavismo today is burdened by a fundamental paradox. How the paradox is addressed will affect the future of Venezuela. Maduro leads a movement that both espouses revolutionary ambitions and rests its international and national legitimacy on its electoral mandate. In a revolutionary process, principles cannot be compromised. Yet the electoral logic and the 1999 constitution require negotiation and compromise. For example, a two-thirds vote in the legislature is needed for essential decisions, and with the governing party controlling only 98 seats out of 165, addressing those issues will require building coalitions across party lines.

When Chávez’ performance approval ratings hovered at 60 percent, chavismo could marry an electoral logic with a revolutionary logic. But now, with the country divided, this “revolution through elections” without compromise, negotiation and building wider coalitions is no longer feasible.

Chávez raised tremendous expectations, not only for the distribution of material benefits through continually expanding petroleum revenues, but also for a new form of communal citizen participation in politics. If predictions of a far-reaching change in the balance of power in the global oil market come true, with the U.S. moving into position as a leading oil and gas producer, and the possible decline in average oil prices below $90/barrel, then Venezuela will be forced to revisit its economic model, with the social and political implications that entails.12

Venezuelans have always valued a large state role in distributing petroleum rent. In recent elections, both government and opposition candidates promised to retain and expand popular social welfare programs. Venezuelans also agree that elections are the only acceptable route to power, and the importance citizens place on elections actually underlies the current dispute over the voting conditions and results. But beyond that, Venezuelans lack a consensus on the role of private property in the economy, and on the political rules to shape the relationship between state and citizen. These are the central tasks facing the country.

How This Could Happen

The larger questions and policy matters were mostly on hold while the immediate dilemma—the unwillingness of government and opposition to recognize each other’s legitimacy—was front and center. Until the election dispute is resolved, the opposition will not recognize the legitimacy of the Maduro government. At the same time, the Maduro government refuses to talk with those who refuse to recognize its legality and legitimacy. The fate of the 2013 electoral dispute will determine the longer-term role of elections in Venezuela—that is, whether the opposition adopts a long-term strategy of rejecting election results, or the consensus on elections as the only legitimate means to access power survives and strengthens in Venezuela.

Much of the standoff stems from the divisions within their own movements. Both leaders faced internal pressure to demonstrate their strength and combativeness, and the CNE has reacted defensively to criticism.

As a result, neither candidate handled the surprising election results on April 14 with a strategic eye to the future. Each gave incoherent and inconsistent messages to their followers and opponents alike. And with those inconsistencies and a lack of transparency, the CNE risked its institutional confidence, Maduro risked the legitimacy of his victory, and Capriles and the MUD risked demotivating its supporters if implied claims of electoral fraud went unproven.

In the longer term, it is essential to rebuild the legitimacy of the electoral process in Venezuela. Getting there requires agreements between the government and the opposition on key areas: auditing the electoral registry, establishing stronger regulations for ensuring equity of access to media and transparency of spending in campaigns, replacing ad hoc agreements with a formal set of rules for auditing the electoral system before and after the elections, increasing public education about the extent of these audits and the role of national and international observer groups, and establishing commitments from the campaigns to create a tranquil atmosphere for voting on election day.

The recent past provides reasons to believe the two sides could strike such accords. From 2006 to 2012, the government and the opposition established a working relationship that effectively bolstered the electoral system’s legitimacy, as demonstrated by public opinion polls and record-high citizen participation rates.13 When the tensions from this past electoral cycle subside, a new opportunity could emerge.