Six years after the estallido social (social explosion) that saw massive protests and violent vandalism in what had been Latin America’s most successful country, Chile is still digesting the aftermath. That is clear from the result of Sunday’s general election. This set up a run-off between Jeanette Jara (26.9%), the Communist former labor minister in Gabriel Boric’s government, and José Antonio Kast (23.9%), a radical conservative. No election is settled until it takes place, but it is highly likely that Kast will win the second round on December 14th, since the vote of the various right-wing candidates totaled over 50%. Although Jara may pick up some of the votes of Franco Parisi (19.7%), a populist outsider, and of Evelyn Matthei (12.5%), a mainstream conservative, that is unlikely to be enough.

Left and right have alternated in power in Chile since 2010. But if Kast were to be elected, he would be the most right-wing president the country has had since the end of the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet in 1990. It would break a taboo: until now, Chileans have always voted against anyone or anything associated with Pinochet, as they did against Kast in a run-off in 2021. But it would be symmetrical. The social explosion was followed by the election of Gabriel Boric, the most left-wing president since Salvador Allende, whom Pinochet ousted in his bloody coup of 1973. Perhaps it was inevitable that Chile’s brief swing to the radical left would be matched by one to the radical right.

And yet. Everything suggests that there is a moderate majority in Chile. In 2022-23 Chileans voted against two new draft constitutions. The second was inspired by Kast. The first was a utopian document of the radical left; Boric never really recovered from his association with it. Having excoriated the centre-left Concertación coalition which governed for much of the period from 1990 to 2018, Boric swiftly adopted many of its policies and appointed some of its people.

Two things lie behind Kast’s likely victory next month. One powerful legacy of the social explosion is a rejection of elites. That brought Boric to office in 2021. The big losers this time were not just Matthei, but also Carolina Tohá. A competent politician of the moderate left whom Boric appointed as his interior minister, she fell at the first hurdle, losing badly to Jara in a primary. The big surprise in the election was Parisi, a campaigner with no clear ideology apart from strong anti-elitism.

The second factor favoring Kast is a change in what worries Chileans. Boric focused on inequality and inclusion. But these were quickly displaced as public concerns by crime, immigration and economic growth. Coinciding with, and in part caused by, the arrival of some 700,000 Venezuelan immigrants, large-scale organized crime took hold in Chile for the first time (though this owed more to the loss of state control in poorer neighborhoods during the social explosion and the pandemic). Boric and Tohá tried to respond: the murder rate, still low by Latin American if not Chilean standards, has stabilized in the past two years. But fear of crime remains high. Kast’s promises of an “implacable” plan and an “emergency” government against crime, of deporting illegal immigrants and building a ditch on the northern border to stop others, has found an audience.

So has his implicit promise to return to the high rates of economic growth of the final years of the dictatorship. The underlying factor behind anti-elitism and the turn to the right is a decade of relative economic stagnation in which income per person has risen by only about 1% a year. For younger generations, with more years of education than their parents (often acquired at their own expense), that has engendered frustration.

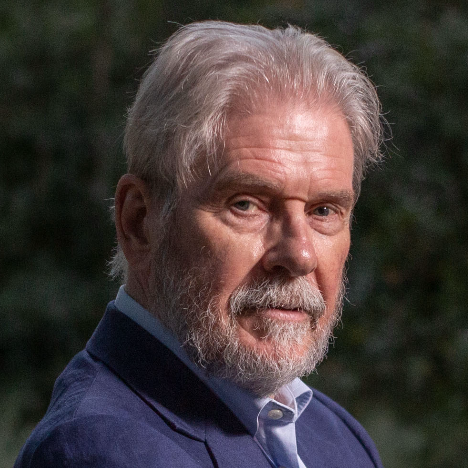

Assuming Kast wins, what would it mean for Chile? He is a political friend of Javier Milei in Argentina and of Vox in Spain and looks kindly on Donald Trump. But there are as many differences as similarities among leaders of the new hard right. When I spoke to him last year he insisted he is a democrat (and several on the left agree with that). The worry he evokes is not authoritarianism so much as the shallowness of his proposals. Chile is a more diverse and socially liberal country than it was under Pinochet. Kast lost a referendum on his constitutional draft partly because of its dogmatic opposition to abortion. He may have learned from that.

“We want to shrink the state and lower the tax burden,” he told me. He has promised to slash $6 billion from public spending in 18 months, though he hasn’t said how. At around 27% of GDP, total public spending in Chile is relatively low for a country of its income level (around $17,000 per person). Certainly, the country would benefit from deregulation (something Boric recognized, belatedly) and clearer incentives for private investment. Public spending needs to be more efficient. But the state needs to organize more investment in education, health and infrastructure as well as to encourage economic diversification.

Boric was rendered more moderate partly by his sense of political reality, but also by his lack of a majority in Congress. To command parliamentary support, Kast would have to negotiate with the center-right, which should be a moderating factor. One of the most useful things he could do is organize a political reform to reduce fragmentation. The 150 seats in the lower house of Congress will be shared between 18 different parties grouped in five coalitions.

Chile has been through six years of turmoil. Kast’s supporters think he can end that by restoring rapid economic growth and by making Chileans feel safer. Critics fear a conservative dogmatism that would intensify social conflict. Whoever proves to be right, Chile has not derailed. The fundamentals–democracy, a market economy, and the rule of law–remain in place. There is every reason to hope that at least this will remain the case.