This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on trends to watch in Latin America in 2025

At first glance, Stefania Bril’s photographs of São Paulo impart a gritty social realism, just barely blunted by witty humor. But in one central image in a retrospective of her work currently on view at the city’s branch of Instituto Moreira Salles (IMS), what comes through above all else is tenderness.

“Boy reading comics in a supermarket cart” shows an empty street in the wealthy Jardins neighborhood, closed off by the concrete walls of private residencies. A boy lies with his body extended from the sidewalk to the inside of a shopping cart tipped on its back, handle lodged where curb and asphalt meet. Loitering in an improvised chaise longue, his body cuts across the vertical strips of the composition (sidewalk, verge, street), a tender dissident making the city his own.

Stefania Bril was born in Poland in 1922 to a Jewish family that survived the Holocaust with help from a resistance organization and falsified identities. She moved to Brazil in 1950, working in biochemistry labs until a course at the independent school Enfoco moved her to dedicate herself entirely to photography. Desobediência pelo afeto collects 160 images from IMS’ archive of Bril’s work, alongside her criticism and activity in the city’s cultural scene. Almost erased from the art world since her death in 1992, an institutional effort is now being made to recover her critical eye for urban life.

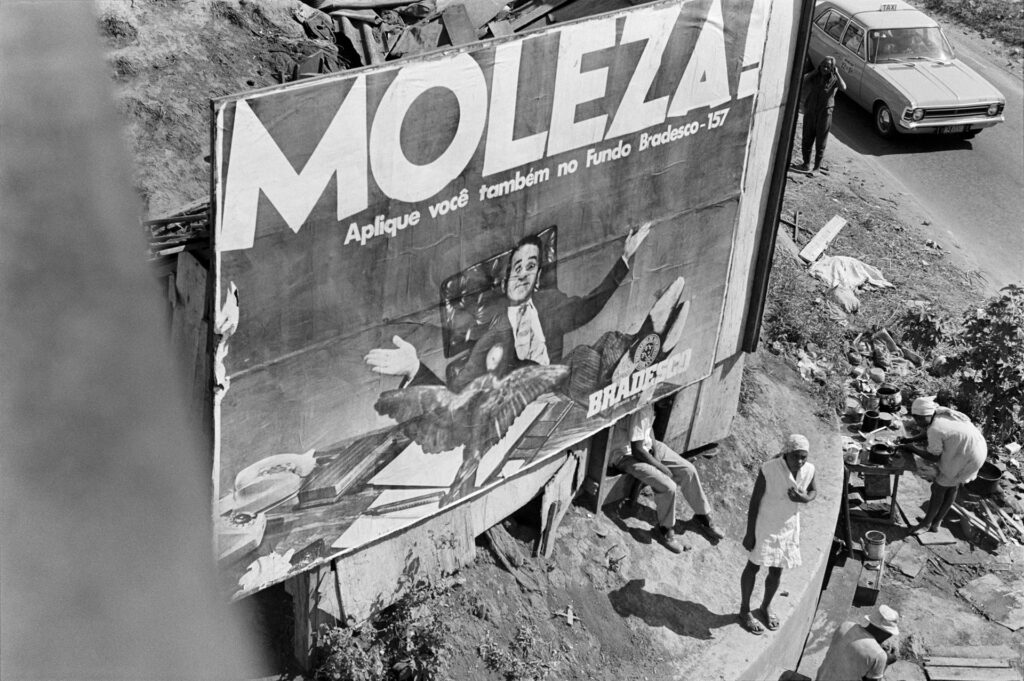

Early street photography, as pioneered by the Magnum agency, was geared towards the exceptional—war, crime, and spectacle. Instead, Bril focused on daily life: a Black mother in headwrap leading her children through a parking lot, one of them defying her lead; shoeshine boys stealing a few minutes of sleep on a downtown sidewalk. In her criticism, Bril argued that a female photographer can “dive with more drive and passion into the world of ‘minorities,’ identifying herself with them—the world of children, women, the rejected, and the elderly.” She defused these images with humor that often came in juxtapositions of words and actions. In one photo, under a sign that says, “Don’t step on the grass,” a suited man sleeps face down, only his feet sticking out past the perimeter of greenery.

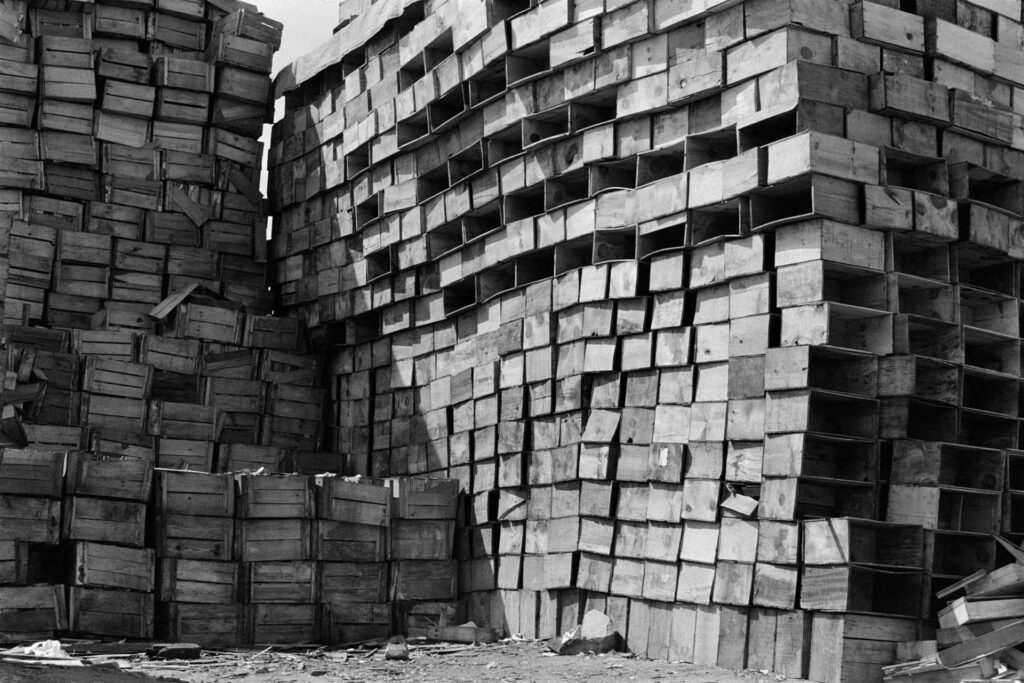

But if Bril is a chronicler of the everyday, she also records a bigger picture: a São Paulo caught in a violent growth spurt, overseen by the country’s military dictatorship amid the promise of an “economic miracle.” Her photograph of giant walls of “lettuce crates” at the State Center for Food Supply (CEASA), founded in 1969, symbolizes the infrastructure developed for São Paulo: monumental, homogeneous and precarious. Bril’s singular images are found at the seams in which the everyday and the structural intersect.

The hope that unveiling the city’s hidden actors could spur structural social change became the organizing task for Bril’s Casa de Fotografia Fuji, a cultural center she saw as a home for photography that “defogs one’s gaze, instigating perception.” For inspiration, she looked to the great New York City journalist and photographer Jacob Riis, whose “photos changed laws” at a time when words seemed impotent. But tensions between Bril and Fuji would lead to her dismissal two years after her center’s opening.

Today’s São Paulo remains similar in many ways to Bril’s—brutally unequal, racked by paroxysms of growth, where people work to make themselves at home amid vast slabs of concrete. Since Bril’s time, the photographic image has become hegemonic, blinding instead of defogging perception. But that doesn’t diminish the resonance of Bril’s affection. She writes: “São Paulo is an addiction. We criticize, complain, but enjoy it. And despite the aural and visual onslaught of media, I continue to believe in another simple and authentic ‘addiction’: a handshake, a rag of tenderness, a breath of communication.”