LIMA — Years ago, China promised Peru it would transform the country into the “Singapore of Latin America,” offering access to its vast market and other Asian nations. In return, China would receive commodities to fuel its growth. The recent Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit, held in Lima in early November, showed that this bargain is intact. So far, both countries seem content with their alliance, but global tides are changing, and the U.S. and Europe are wary of this thriving relationship.

The most recent illustration of deepening Peru-China ties is the $3.5 billion Chancay megaport, located 46 miles north of Lima and inaugurated in November during Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit for the APEC summit. China’s state-owned Cosco Shipping built the facility, which is jointly owned by Cosco and Peru’s Volcan, a mining company. Peruvian authorities view China’s $1.3 billion investment in the port, the nation’s eighth Pacific-facing hub, as a great opportunity to integrate into international supply chains, boosting long-term economic growth.

But the port and its promise were emblematic backdrops for the longstanding geopolitical confrontation between China and the U.S., which was in the air at the summit. While it’s encouraging that both U.S. President Joe Biden and President Xi attended the forum, the elephant in the room was President-elect Donald Trump’s threat to escalate the trade war with China.

This will inevitably affect Latin America, where China’s presence is growing. For the first time at an APEC conference, its substantial infrastructure presence—developed under its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that has yielded agreements with 22 countries in the region—came into focus. It is now possible that the region could overtake Africa as China’s priority for global infrastructure expansion.

In Peru, the new port reflects a strengthened relationship with China and Asia. Last year, Peru posted a $9.3 billion trade surplus with China, a marked contrast to its $1.8 billion trade deficit with the U.S. Over the coming years, the U.S.-China competition in Peru is set to intensify. The critical question is: Can Peru maintain neutrality, or will it be forced to pick a side?

Can Peru stay neutral?

It would be difficult for Peru to avoid favoring China, at least to some extent, but this is the case for most Latin American countries that have increased trade and financial exposure to China. The Trump team has indicated that it plans to impose 60% tariffs on Chinese goods imported via Chinese-owned ports. In Peru, this would apply to Chancay and the new San Juan de Marcona port in the state of Ica, south of Lima, where China’s Jinzhao Peru SA was awarded a 30-year operating concession.

Even so, Peru could still use any of the seven ports owned by other countries to expand into the U.S. market. While China’s recent business acquisitions in Peru and U.S. concerns over Chancay have received a great deal of media coverage, little attention is given to the fact that the U.S. has investments in two ports in Peru and is planning a third deep-water facility, like Chancay, in the state of Arequipa, south of Lima.

Meanwhile, Trump’s recent statements signal that he will escalate a political confrontation with Mexico over immigration and trade. This makes it more likely that his administration will try to maintain the constructive relationship with Peru that the Biden administration reinforced during the APEC conference. After meeting with Peru’s President Dina Boluarte, President Biden referred to Peru as “a valued partner.” For his part, Brian Nichols, Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs, reinforced the message by saying: “We are going to prove that the best partner for Peru is the U.S.”

During his visit, Biden confirmed support for Peru’s counter-narcotics operations with a $65 million security assistance package that includes the planned transfer of nine Black Hawk helicopters. He also highlighted the donation of 100 California Caltrain locomotives to Lima and discussed expanded cooperation with Peru on space exploration, including a memorandum with NASA on a sounding rocket campaign. (Sounding rockets carry scientific instruments into space.)

Key flashpoints

All that said, Chancay remains a sore spot. The U.S. has raised two serious concerns that Peru must carefully manage. First, General Laura Richardson, the recently retired head of U.S. Southern Command, commented that the Chinese navy could use the Chancay port strategically. “This is a playbook that we’ve seen play out in other places,” Richardson said.

Second, Cosco Shipping, the Chinese state-owned firm that built the port, is attempting to avoid Peruvian government oversight. It is claiming to the judiciary that it is a private port, not a government concession, and so should not be monitored by the Organismo Supervisor de la Inversión en Infrastructura de Uso Público (Ositran).

Ositran would likely monitor Chancay for anti-competitive behavior to prevent it from setting low prices that undercut other ports. But such monitoring would also make it more difficult for the Chinese navy to use the port openly or covertly.

For their part, Peruvian officials have argued that security concerns are overblown and that any foreign naval activity at the port would have to be authorized by Peru’s military. Still, U.S. authorities are following this matter closely.

China’s other gains

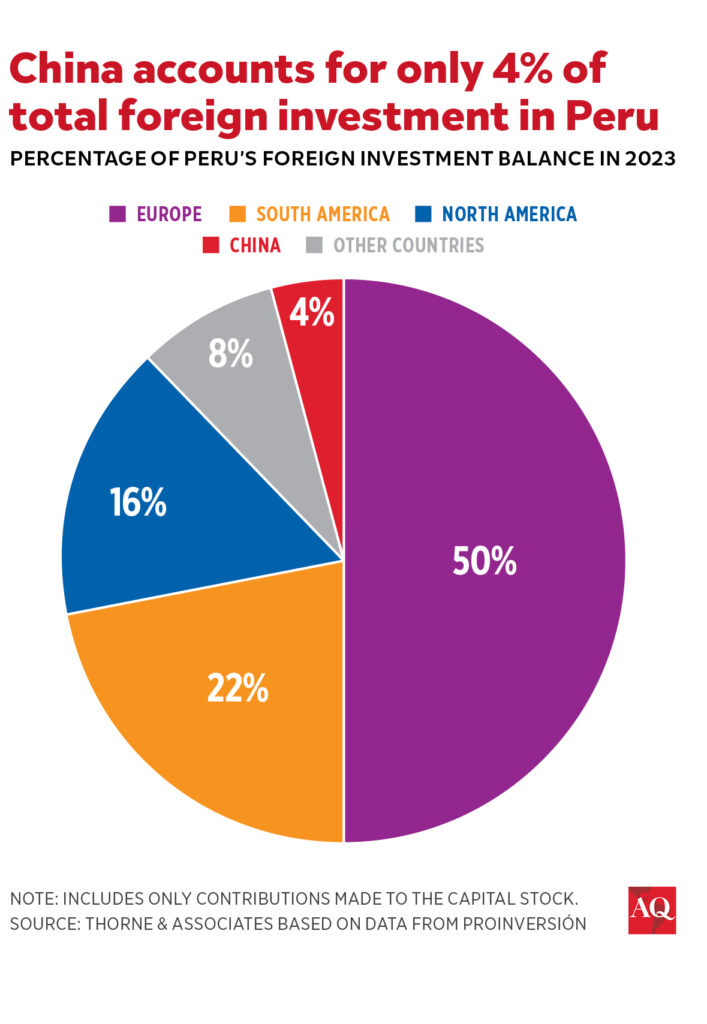

Even apart from Chancay, Peru is drawing ever closer to Asia. Recent acquisitions in Peru by Chinese businesses resulted from divestment by U.S. and European firms. These include the decision by the U.S.-based Sempra to sell Lima’s electricity network company, Luz del Sur, to China’s state-owned Three Gorges; Switzerland’s Glencore selling the Las Bambas mine to China’s Minerals and Metals Group (MMG); and Italy’s ENEL selling its Lima energy-distribution company to China’s state-owned China Southern Power Grid International (CSGI). However, China’s Peruvian assets represent a marginal share compared with those of Western economies, according to Peru’s central bank.

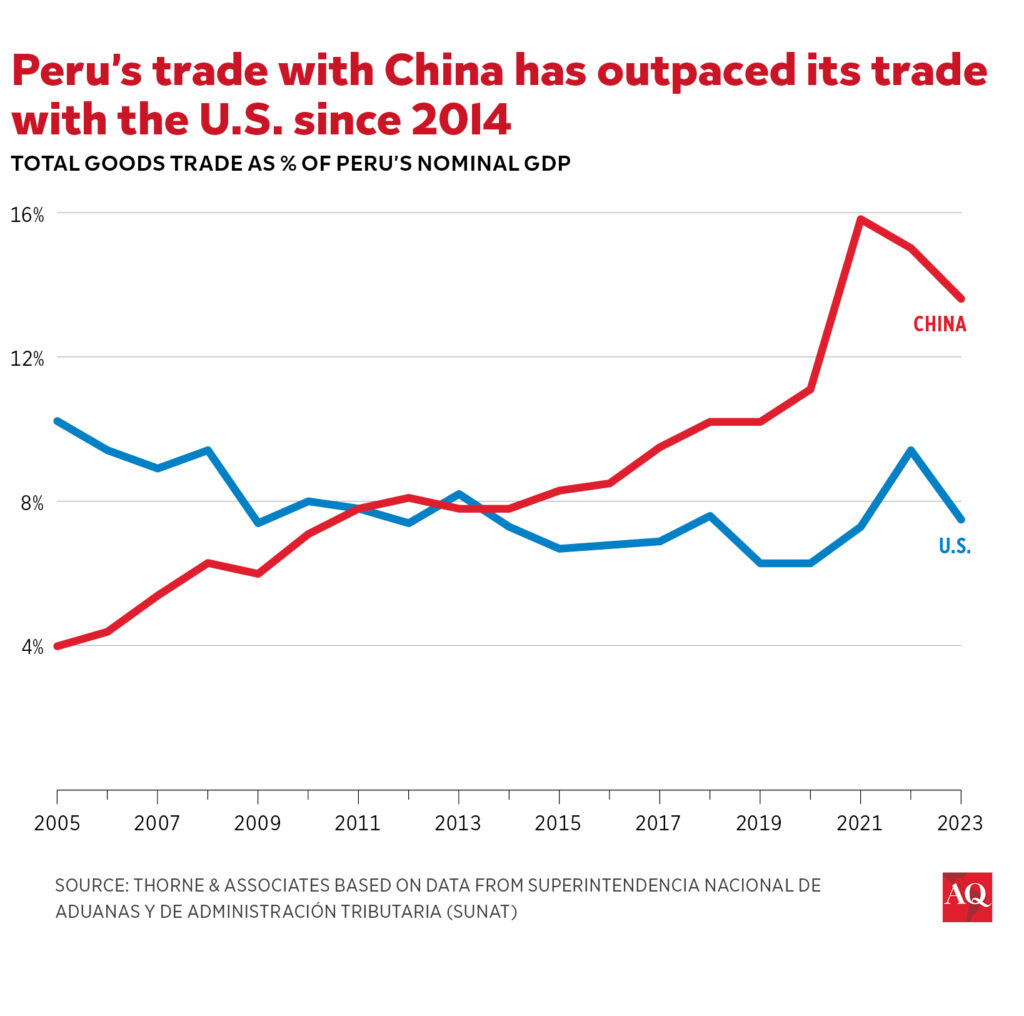

Peru has benefited extensively from the free-trade agreements (FTAs) signed in 2010 with China and in 2009 with the U.S. These two countries are Peru’s largest trading partners. In recent years, Peru’s trade with China has outpaced that with the U.S. For instance, using the ratio of total goods trade (exports plus imports) to GDP, trade with China grew from 7.1% in 2010 to 13.6% in 2023, while trade with the U.S. fell from 8% to 7.5%. However, this excludes services trade, where the U.S. has a larger share.

As a small, open economy, Peru relies on a multilateral approach and has benefited from greater trade integration since the 1990s. In fact, a new free trade agreement with Hong Kong during the APEC summit brought its total to 23 FTAs, one of the highest numbers in the world. Peru’s policy of trade integration was a major driver of its rapid growth in 2000-16, and if it is forced to choose sides between the U.S. and China, further integration could be at risk.

Squaring the circle

Although Peru has recently made moves favoring China, it is difficult to see this continuing in the medium term. First, aside from its geopolitical position, Peru has little to offer China beyond commodities. Peru’s local market is small, and offers little advantage to China’s companies. Meanwhile, Peru’s benefit from China’s trade is marginal. China has not given Peru much access to technology or knowledge transfer, for example, to help it move up the value chain.

President Boluarte’s view is different and highlighted the role of new port of Chancay in expanding South American trade with Asia. At the port’s inauguration, next to China’s President Xi Jinping, Boluarte described Chancay as part of “the Inca trail that at one point [with] our Inca empire extended throughout South America,” adding that it “allows us to cross to the Asian world and connect these two immense continents.”

But our institutional differences divide. Peru’s constitution adheres strictly to the free market, the rule of law, civil and individual rights, and democratic principles. It may well be the most modern pro-market constitution in the Western Hemisphere. This is very different from China’s principles, which are based on state capitalism, autocratic government, and limited respect for civil and individual rights.

Long-term trends favor Peru’s relationship with the U.S., but it’s unclear whether this will force Peru to miss out on opportunities with China. In the end, for Trump, picking a fight with Peru may make little sense. Its small, open economy with well-diversified trade makes it resilient. And Trump needs friends in Latin America—some may consider only Argentina, Chile, and Peru reliable allies. A friendlier approach seems more logical and more likely. The U.S. knows that Peru has a critical geopolitical position, the commodities needed for energy transformation, and similar democratic, pro-market principles. Although Peru’s current unpopular government may make things difficult, the next administration will offer a fresh start.