TEGUCIGALPA—When Xiomara Castro became Honduras’s first female president in 2022, she pledged a massive departure from the previous 12 years of National Party (PN) rule. PN officials had gutted state institutions and worked at the highest levels with organized crime as schools and hospitals languished and a record number of Hondurans fled for the U.S.

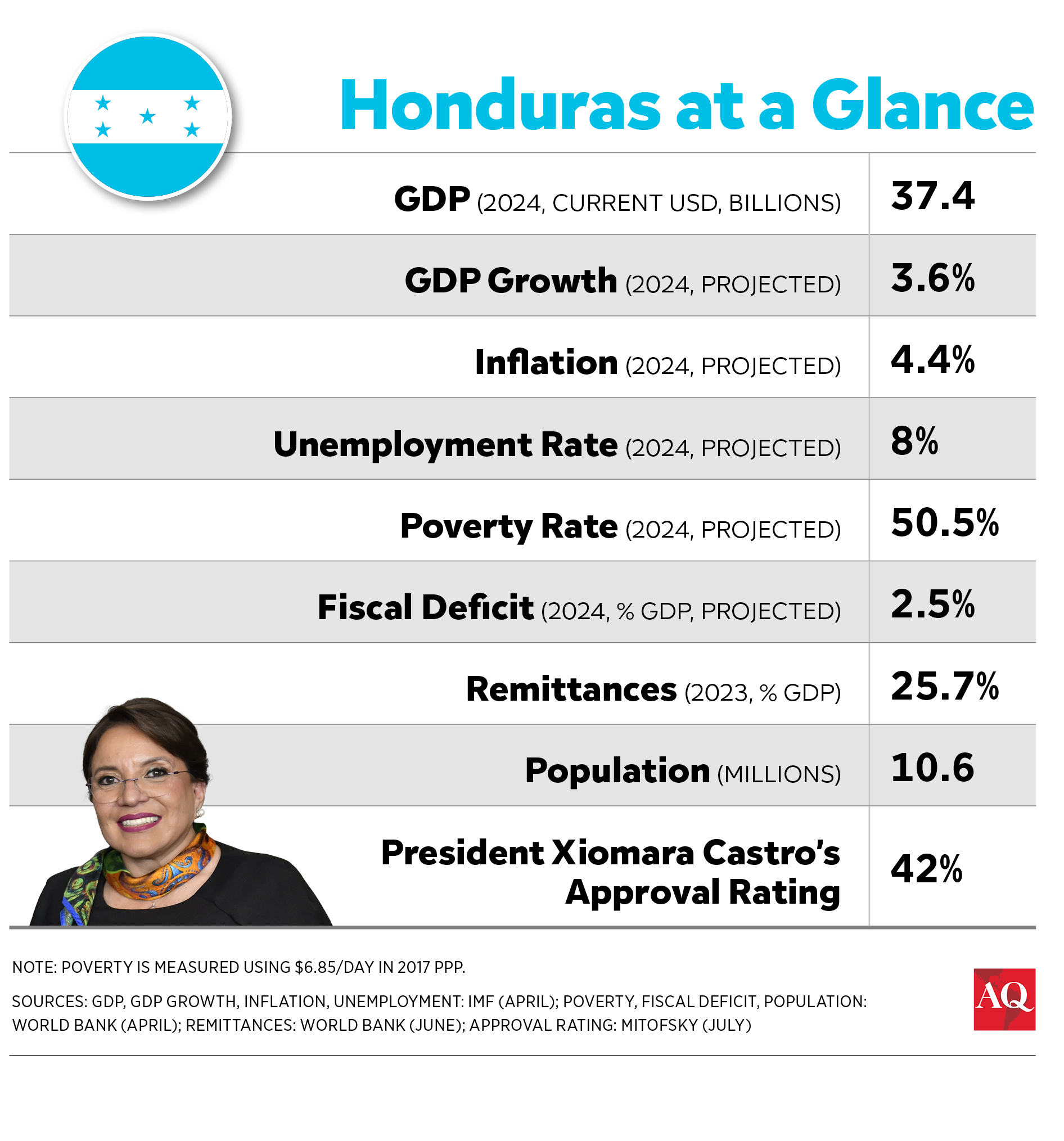

Since then, Castro has partially delivered on promises to crack down on street crime, improve public services and welfare programs, and fix roads. GDP growth reached 3.9% in the second quarter of the year, and the IMF projects it will remain over 3.5% for the next five years. Her successes on these bread-and-butter issues put Castro’s approval rating at 61% in April, according to Mexican pollster Mitofky, making her LIBRE party competitive ahead of the national elections in November 2025.

But her core campaign vows were to restore institutionality, combat corruption, and deliver an international anti-graft commission modeled on Guatemala’s CICIG. Now, Castro’s approval rating is falling as her anti-corruption initiatives seem to be sinking under the weight of new scandals roiling her inner circle.

As public skepticism mounts, Castro and LIBRE will try to prove over the coming year that Honduras is turning a corner under their leadership. For now, modest progress on crime and kitchen-table concerns may outweigh voters’ concern over grand corruption.

An about-face on extradition?

The promised transformation seemed underway when, just three months after Castro took office, she extradited her predecessor, Juan Orlando Hernández, to the U.S. Once a U.S. ally, Hernández is now serving a 45-year sentence for trafficking drugs and weapons. Much of the public seemed ready to believe that stability and accountability were returning for the first time since Castro’s husband, former President Manuel “Mel” Zelaya, was deposed in a coup in 2009.

But in August, Castro’s brother-in-law, Carlos Zelaya, resigned as president of Congress after he admitted to meeting with drug traffickers in 2013, and a video of the meeting circulated in which he appears to negotiate bribes. In the video, the traffickers can be heard alleging they previously sent bribes to Castro’s husband, former President Zelaya. Just after Castro’s brother-in-law resigned, his son (and Castro’s nephew) also resigned as defense minister.

In the midst of all this, Castro denounced Honduras’ extradition treaty with the U.S. She said it was unrelated to these revelations and was instead in response to U.S. Ambassador Laura Dogu’s condemnation of a meeting between Honduran military leaders and Venezuela’s defense minister, Vladimir Padrino López, whom Dogu called a “drug trafficker.”

In an open statement posted on X, Castro criticized U.S. policy toward the country. “The interference and interventionism of the United States, and its intention to direct the politics of Honduras through its embassy and other representatives, is intolerable.”

This was the latest in a series of diplomatic skirmishes with the U.S., by far the country’s largest trading partner. In July, Castro congratulated Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro after he declared victory in an election most Latin American leaders have condemned as fraudulent, and last year her administration cut ties with Taiwan in favor of China. In 2022, Castro’s administration scuttled the domestically unpopular “special investment zones” known as ZEDEs, distressing some U.S. investors with this and other reforms.

Even so, the countries continue to cooperate closely on security; the U.S. maintains a military base in Honduras, and the new defense minister, Rixi Moncada, met with U.S. counterparts at the Pentagon and SouthCom headquarters in October. Meanwhile, extraditions to the U.S. continue, most recently with an alleged fentanyl trafficker on October 23.

The resignations, extradition statement, and delays on the UN anti-graft commission “give the impression that corruption is still ingrained, that this administration has the same narco-vices as the last administration,” Leonardo Pineda, a political analyst in the northern city of San Pedro Sula, told AQ. “The public is disappointed.”

In early September, Gabriela Castellanos, director of Honduras’ National Anti-Corruption Council, an NGO, urged Castro to resign. “This request is based on the serious accusations of drug trafficking that have been presented against your family, whom you have appointed to work in the state,” Castellanos wrote to Castro in an open letter.

LIBRE may still be able to restore voters’ trust. The party will benefit from its staunch internal opposition to presidential re-election, meaning it will probably have a fresh face on its ticket as opposed to Castro or Zelaya. And Castro still says the UN commission will soon be created; she delivered a second draft proposal to the UN in September.

(Photo by Orlando Sierra/AFP via Getty Images)

LIBRE’s popularity

Castro’s government is spending around 67% more than the last administration on its popular Red Solidaria social programs—a total of about $188 million—tripling the number of families receiving cash transfers to over 400,000 while reducing the average amount received. Five new hospitals are under construction, and the health system has much-improved access to medicines and equipment. According to government data, over 3,000 schools have been refurbished, and the administration has worked with the UN and other organizations to provide free school lunches nationwide.

Meanwhile, her government’s crackdown on street crime, modeled on that of neighboring El Salvador under President Nayib Bukele, has yielded modest successes. The murder rate has fallen from 34.5 in 2023 to a predicted 26.5 in 2024, according to the National Violence Observatory of the National University of Honduras, but it has entailed a “temporary” state of exception renewed since 2022. The strategy has been widely criticized by rights groups for violating civil liberties—though it has drawn even more ire locally for failing to curb extortion.

The government appears poised to double down, with more deployments of police and soldiers to crime hotspots, more searches, and arrests—as well as a reform of the prison system, moving prisoners from urban facilities to remote ones to prevent gangs from coordinating operations from within. Around 21,000 people are incarcerated in 30 facilities nationwide, and the Castro administration has fast-tracked an “Emergency Confinement Center” to house 20,000 prisoners—an indication that the government is preparing to accelerate the pace of detentions. Public support for the government’s crime policies will likely hinge on whether they manage to reduce extortion.

Investment, inflation

On the economy, the government has been forced to walk a fine line between attracting investment, controlling inflation—currently at 4.4%—and maintaining U.S. dollar reserves. The central bank has allowed the exchange rate to fall, part of an agreement with the IMF, pushing the cost of living higher.

Some of the pain, however, will be offset by rising remittances. Honduras received about $9 billion in remittances in 2023—equivalent to 26.1% of GDP, according to the World Bank. And on October 18, the IMF reached a staff-level agreement with Honduras. It recognized that fiscal policy “remains prudent, public investment continues to expand, and the authorities have recently begun normalizing monetary and exchange rate policies.” The news came after the multilateral lender approved $822 million for the country to balance its payments needs and support the government’s “economic and institutional reform agenda over the next three years.”

This deal and the gradual depreciation of the national currency may also help to attract investment, which is badly needed to provide work to the estimated 2.3 million people—of a population of around 10 million—who lack formal employment. Job creation has been a major weakness of the administration, and in recent months, seven clothing maquilas have announced they would shutter in the wake of pandemic disruptions, which would put some 30,000 people out of work.

LIBRE will be vulnerable to an election challenge from candidates eager to take up the mantle of aggressive anti-corruption reform after Castro’s government faltered. However, if Castro reaches a deal with the UN commission in the coming months and the government’s crime crackdown finally dents extortion, that may be enough to convince voters that the country has turned a corner.