Argentina has seen an unprecedented wave of corruption charges this year against high-profile individuals, plus the arrest of members of the business elite, union leaders, and former government officials. Even former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (2007-15) was formally charged in May over her alleged role in the sale of future dollar contracts by the central bank shortly before leaving office (she says she is innocent). The surge of anti-corruption enforcement actions has prompted inevitable comparisons with neighboring Brazil, where authorities in the “Car Wash” investigation are prosecuting the largest corruption scandal in Brazilian history.

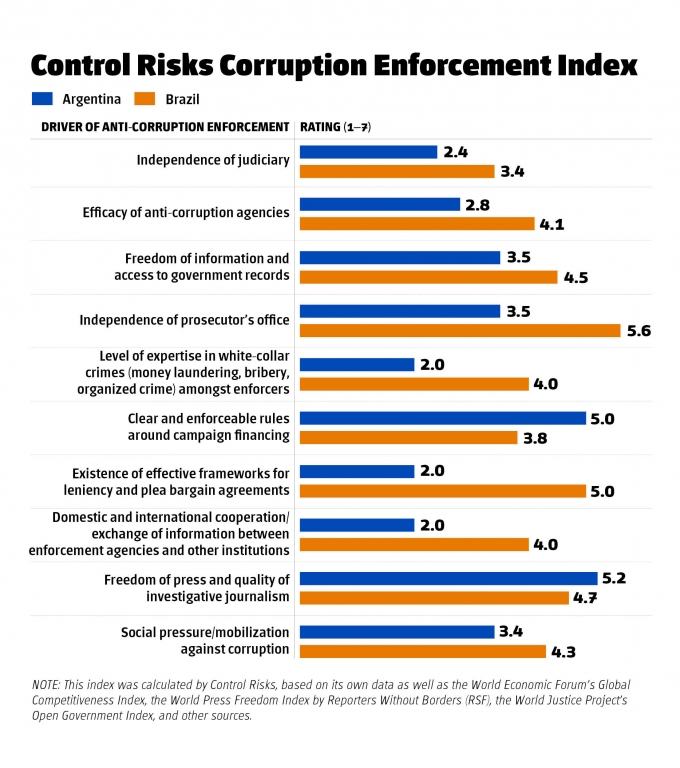

So, is Argentina the next Brazil? The similarities are striking. In both countries, the maturing of democratic institutions has been accompanied by greater transparency in government records, while independent media plays a critical role in exposing malfeasance in the public sector. Meanwhile, civil society rightly harnesses the tools of the modern world to pressure for greater government accountability. Yet as our new Corruption Enforcement Index (CEI) shows (see chart below), in practice Argentina and Brazil have very different legal environments – and could therefore see very different results.

Unlike other indexes (including that prepared by Transparency International), our CEI index does not measure perceived levels of corruption in a country. Instead, the CEI attempts to measure how well-equipped a country and its institutions are to detect and effectively punish corruption. We used a variety of sources, including the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index, the World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders (RSF), and the World Justice Project’s Open Government Index – in addition to our experience and expertise in these markets.

In Argentina, political change has undoubtedly been a driver of anti-corruption enforcement. Fernández undermined the capacity and independence of watchdog institutions during her two terms in office, appointing government allies to lead them, scaling back budgets and restricting access to information on public spending. Meanwhile President Mauricio Macri, elected in December 2015 with a mandate to clean things up, has partially reversed the Fernández legacy and pushed reforms to provide prosecutors additional tools to tackle corruption. The Law of the Repentant – approved by the Senate in September and likely to be sanctioned by the Chamber of Deputies before year-end – expands the legal framework for plea bargaining to cases of corruption. Another piece of legislation, which would significantly increase the stakes for companies by creating corporate criminal liability in cases of corruption, is currently being drafted.

There is no question that the proposed changes in Argentina draw on the experience of other Latin American countries in their quest against graft – particularly Brazil. Prosecutors working on Car Wash would not have advanced so rapidly and deeply in their investigations had they not been able to rely on information provided through 70 or so plea bargain agreements, in addition to unprecedented levels of cooperation and information exchange between international enforcement agencies. Similarly, Brazil’s 2014 Clean Company Act sets clear incentives for companies to co-operate with authorities through signing leniency agreements. However, a closer look at our key drivers of anti-corruption enforcement reveals that Argentina has a markedly steeper hill to climb when it comes to delivering long-term progress in transparency.

Argentine courts rank near the bottom of the World Economic Forum survey when it comes to judicial independence: 121st of 138 countries, behind Brazil (79th) and Mexico (105th). Court rulings are subject to a high degree of political, personal and partisan interference. Members of the judiciary are insufficiently trained, while courts are overloaded. Consequently, corruption cases are rarely brought to trial and, when they are, convictions and application of penalties are few and far between. Impunity is still the dominant theme.

The Macri administration has invested resources to combat corruption, however it will take years to overcome the devastating effects of a decade lost to under-resourced enforcement agencies and political interference. One example is the level of activity of the Anticorruption Office, which can open investigations into allegations brought by various sources, including government agencies, whistleblowing by citizens and the media. The Office initiated 243 new investigations in the first six months of 2016, a moderate improvement over the 216 opened in the same period last year. But it is a far cry from the over 700 investigations it started in the first six months of 2004.

One of the consequences of Argentina’s enforcement hiatus during the Kirchner era is a flat learning curve for law enforcement, which currently lacks meaningful experience in handling large and complex investigations. Additionally, communication channels between the different enforcement agencies are scarce, which means cooperation between them is limited and relatively ineffective. Meanwhile there is deep distrust of government by civil society, which is compounded by poor engagement from oversight bodies, and the lack of formal channels to communicate and interact with key external stakeholders. The fact that investigations remain disproportionately focused on members of previous administrations also limits the public support they receive. Like Brazilians, Argentines seek greater transparency, efficiency and accountability from their current government, and are tired of looking through the rear view mirror.

Argentina is making significant and encouraging progress when it comes to tackling corruption, but the government must address a series of institutional weaknesses if it is to transform the current corruption crackdown into a permanent feature of Argentine democracy. Experience from Brazil and other countries leaves no doubt that legislative improvements and freedom of the press are necessary but insufficient to guarantee such change. Strong institutions such as an independent judiciary, prosecutor’s office and anti-corruption agency, relevant expertise and experience of enforcement agencies, and a strong framework for plea bargains and leniency are critical tools to effectively combat corruption.

—

Favaro is the lead Brazil analyst and Aalbers a Partner and Brazil Country Director for Control Risks, the international risk consultancy. Both are based in São Paulo.