Not long ago, Bolivia was considered one of the few macroeconomically well-behaved populist governments in the Western Hemisphere. But things have been different in recent years. The country has gone from its accelerated growth rate, improved income distribution, and international reserves accumulation path (which earned the praise of the IMF in 2013) to a nation with minimal reserves, distorted relative prices—with shortages of fuel, milk, bread, butter, and other essential goods—and a bloated public sector.

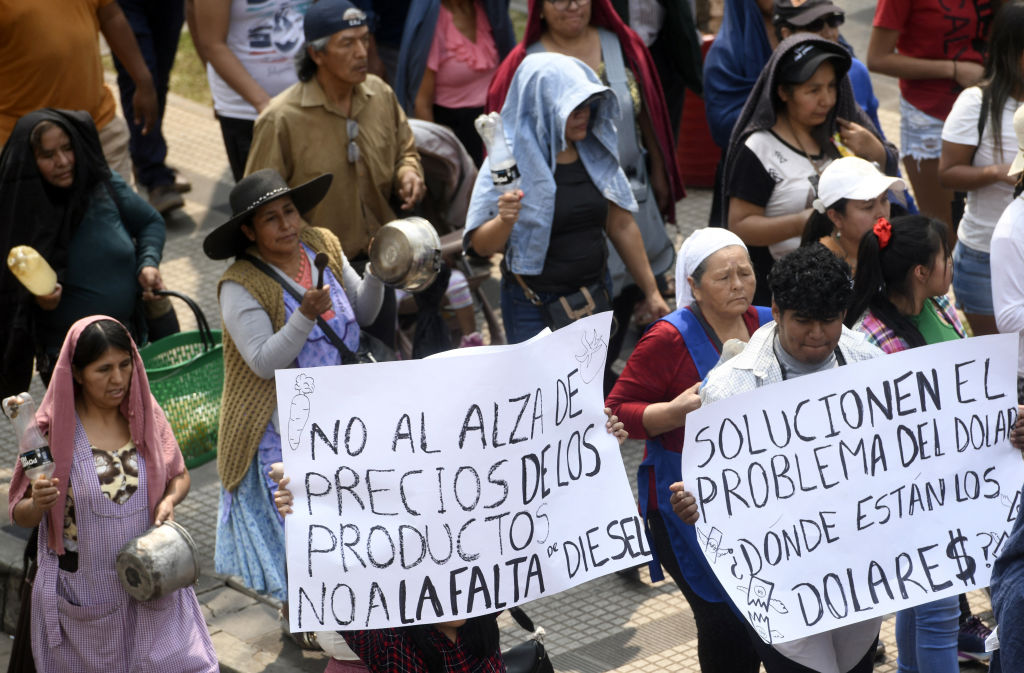

On a brief visit to La Paz in August, I witnessed echoes of this new reality on the streets, and what I learned about the most recent economic developments left me extremely concerned. The descent to the current situation has been gradual, but significant structural reforms that will reshape the government’s function and reach are needed with some urgency.

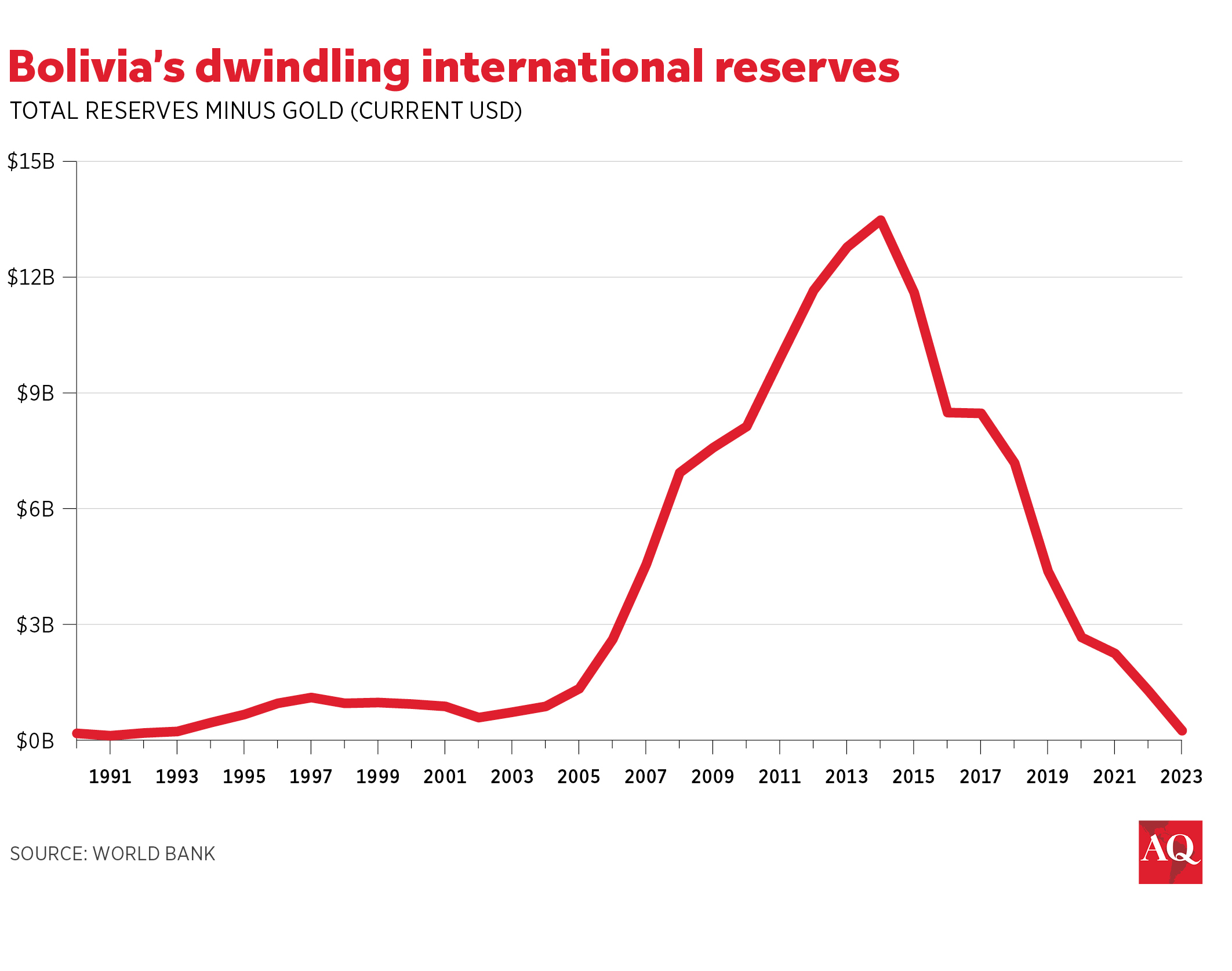

The success of the first decade of Evo Morales’ presidency, who ran the country from 2006 to 2019, led the former finance minister and current head of state, Luis Arce, to write a book lauding the Bolivian economic model. However, Arce didn’t adequately acknowledge the crucial role of the substantial external windfall in the country’s economic performance. From 2003 to 2014, as the region enjoyed a commodity boom, the nation was the second-largest beneficiary of higher export prices, behind Venezuela. During those years, Bolivia experienced a cumulative income windfall estimated at 200% of its GDP, and in late 2014, the nation’s international reserves reached a record of almost $14 billion. Still, once the price of natural gas plateaued and production began to decline, the government opted to use its reserves to sustain growth and consumption.

The strategy reversed the macroeconomic dynamics: current account and fiscal balance surpluses turned into deficits, central bank lending became the preferred instrument to finance this unsustainable path, and international reserves evaporated. The currency has remained fixed, and price controls have been in place to mitigate the impact of external shocks on the population’s purchasing power.

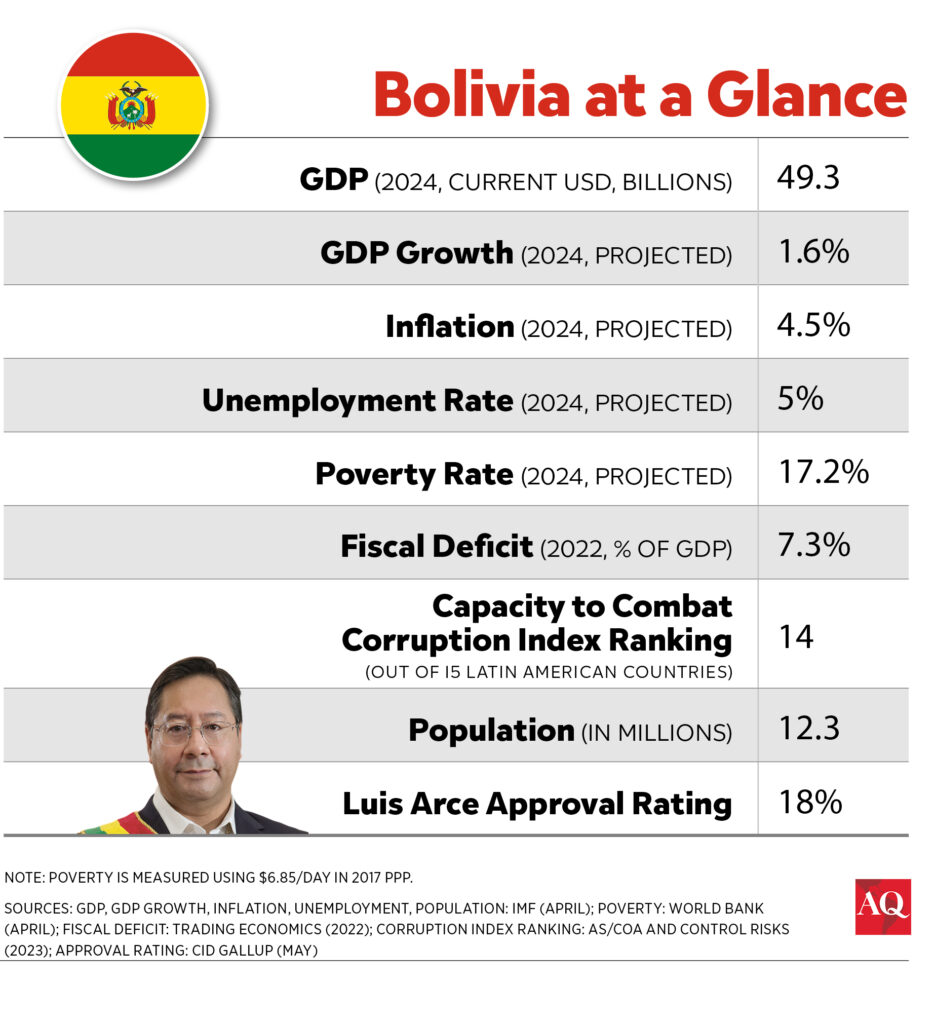

After nearly 15 years of maintaining an official exchange rate of 6.90 bolivianos per dollar and no foreign exchange reserves to support it, Bolivia finds itself on the brink of a currency crisis that the authorities have yet to address. The currency’s official parity is extremely overvalued, as the external income from natural gas is now less than half of the annual average registered from 2012 to 2014, and its real exchange rate is even more appreciated than it used to be during the golden years.

A large fiscal deficit

The sound policies implemented during the windfall era should have provided ample space to cushion the adjustment and execute a smooth transition to a new reality with a weaker currency, lower real wages, and a more prudent fiscal stance supported by tax reform and significant adjustments to public expenditures.

However, for many years, the government chose to defy economic gravity by maintaining a large public sector deficit –7.3% of GDP in 2022—and financing itself with central bank credit. Predictably, this has led to the complete depletion of international reserves, extreme foreign exchange rationing, and the emergence of a black market where scarce foreign currency is priced at nearly twice the official rate.

Currency mismatches are also developing in the banking sector, while the pension system is being forced to purchase excessive amounts of public debt. The buildup of these financial vulnerabilities will make the eventual adjustment even more traumatic.

Needed changes

The sooner the government moves its primary deficit to a surplus, devalues the official rate, and opens space for private sector investment, the smaller the adjustment costs will be. The government should adjust its bloated public sector, reduce inefficient public investment and energy subsidies, and close state-owned firms that do not fulfill a public service nor generate net revenues.

Significant structural reforms should be part of the policy response. The reforms should be geared to attract investment to the hydrocarbon, mining, and forestry sectors. The removal of price controls, credit quotas, and interest rate caps will stimulate the supply of goods and services and the flow of credit.

Additionally, to lessen this cost and cushion the impact of the adjustment on the most vulnerable sectors of society, the country would benefit from a comprehensive program with international financial institutions. Given the deep structural problems that are at the core of Bolivia’s balance of payments crisis, this program should be anchored by an EFF (Extended Fund Facility) from the IMF, designed to address this type of situation. As the next presidential election is less than a year away, a short-sighted political calculus might delay even further the day of reckoning.

Today, the ample buffers that the IMF praised in its 2013 report have been wasted, and the government’s exchange rate fiction is driving Bolivia’s economy towards a deep balance of payments and financial crisis, a very painful adjustment, and most likely another period of political turbulence. The longer the resolution is delayed, the greater the economic cost of the crisis will be.