LANCASTER, Barbados — A new kind of house is under construction in the western Barbados district of Lancaster. These homes—152 of them—are powered, and financed, by solar energy.

Rooftop solar panels sell energy to the national grid, allowing the houses to be sold below market price to first-time home buyers. And the houses are designed with shatterproof windows and solid concrete walls to withstand Category 3 hurricanes. It’s been a successful project—so the next step is to build more, as many as 5,000.

This initiative is part of Roofs to Reefs, the Barbados government’s broad climate resilience plan that seeks to use climate change adaptation as an economic development strategy—helping the island withstand extreme weather and leveraging the energy transition to fuel economic growth.

“Building our climate resilience is key because it will allow us to reduce the impact and recover more quickly from a (climate) event,” said Roofs to Reefs Director Ricardo Marshall. “For a small island developing state, you cannot speak resilience without development, and you cannot speak development without resilience.”

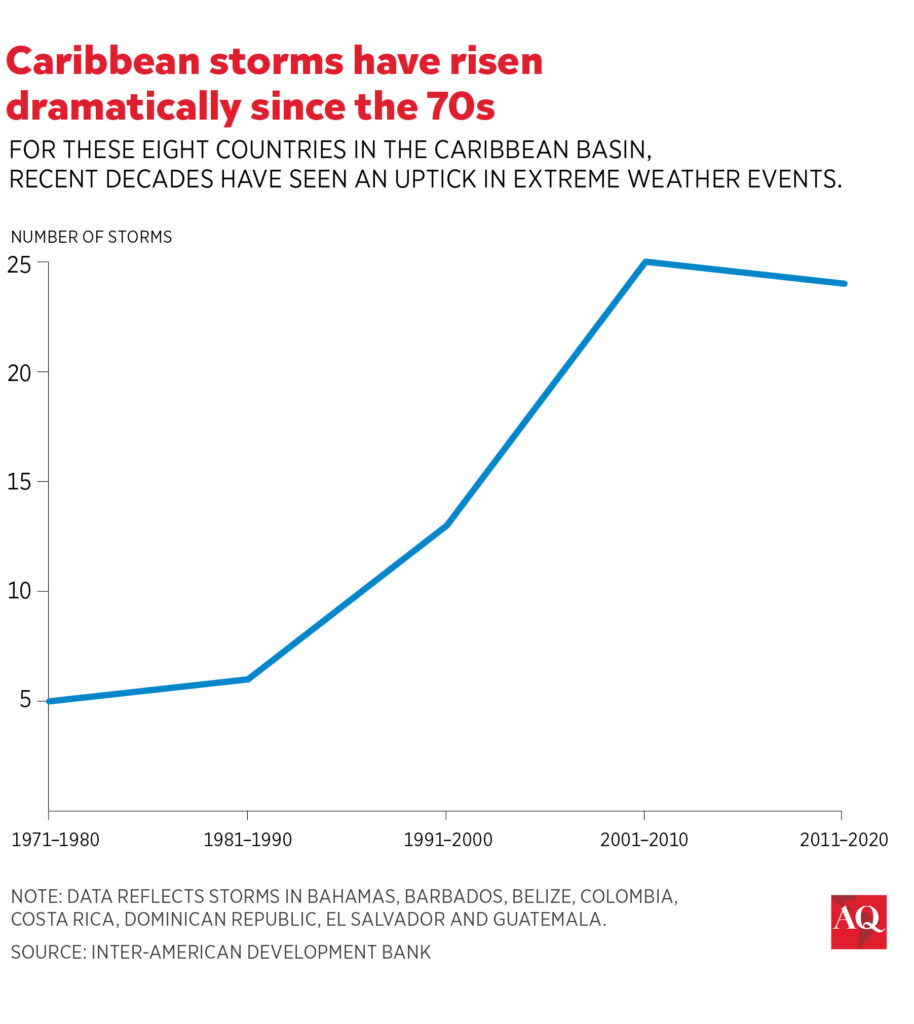

Across the Caribbean region, countries are seeking to build climate resilience in the face of increasingly frequent extreme weather events that pose an existential threat to low-lying islands. A top concern for national leaders across the region is financing: how to pay for these much-needed projects to drive development and shield societies from the effects of climate change.

‘Ground zero’ for the climate crisis

The stakes could not be higher for the Caribbean, which UN Secretary-General António Guterres has described as “ground zero” for the global climate emergency. Densely populated Caribbean coastlines and the region’s tourism-dependent economies are at risk from increasingly frequent hurricanes that can destroy vital infrastructure like bridges and roads. Following severe storms, debt levels in Caribbean countries are 18% higher than what would be expected otherwise, according to research by the Inter-American Development Bank.

Severe weather hits economic mainstays, too: estimates published by the World Travel and Tourism Council show that the Caribbean had some 826,000 fewer visitors than expected in 2017 when Hurricanes Irma and Maria blew through the region, costing the region 11,000 jobs and $293 million in lost GDP.

As Caribbean nations have emerged as leaders in international advocacy efforts demanding that developing countries provide more climate financing and control their own emissions, they’re also taking action at home. In Dominica, the government is developing advanced data for risk assessment and disaster response. Grenada has created water management strategies and a disaster management fund as part of its national climate action plan. Saint Vincent and the Grenadines is developing climate-smart agriculture and fisheries practices and strengthening preparedness and response capacity to climate events.

Climate change mitigation efforts are popular. UNDP research into public opinion on climate change policies showed that over 60% of respondents polled in Small Island Developing States (SIDS) had a favorable view of climate-friendly farming, green businesses and jobs, and solar, wind and renewable power, according to the UNDP Multi Country Office in Jamaica.

The task of building a climate-resilient Caribbean is also a task of improving social conditions in a highly unequal region. Poor Caribbean residents have historically built their own homes, in some cases with little more than sheets of zinc for roofs. Few homes are built with roofs angled at a sufficient pitch to prevent them from being pulled away by gale-force winds. Building codes are sometimes ignored. The damage caused by hurricane Irma in Barbuda was significantly amplified by the lack of enforcement of building codes, according to one disaster management official. Six Caribbean countries would need to invest $1.8 billion to replace substandard housing, according to a CARICOM analysis of a 2016 IADB report.

The financing question

Financing continues to be the biggest challenge. The Caribbean will need an adaptation investment of more than $100 billion, equal to about one-third of its annual economic output, but Caribbean countries have only been approved for about $800 million from climate funds according to a 2023 IMF report. Countries in the region are increasingly looking to the private sector for funding through debt-for-nature swaps that refinance existing bonds and use the resulting savings for climate-related investments.

“The thing that we have a lot of in the region is debt. So looking at ways to restructure debt that help to conserve or adapt is a really key opportunity for us,” said Racquel Moses, CEO of the Caribbean Climate-Smart Accelerator, a non-profit organization aiding the Caribbean with investment for climate action and sustainable development.

Belize in 2021 cut its debt load by 10% of GDP by swapping a $553 million bond, agreeing in the process to spend $4 million per year to protect coral reefs and sea grasses. Barbados in 2022 carried out a similar swap that generated $50 million for marine conservation as part of the refinancing of around $150 million in international bonds. A multi-jurisdiction debt-for-nature swap involving multiple eastern Caribbean nations is currently under study, Moses said.

Barbados is using some of the funds from the debt-for-nature swap to finance marine conservation efforts being carried out under Roofs to Reefs. It is also creating a Blue Green Bank, supported by multilateral lenders, including CAF and the Inter-American Development Bank, that will provide low-cost loans for hurricane resistant homes and a shift to electric vehicles. New homes are now required to be built to resist extreme weather. Barbados already has the Caribbean’s largest fleet of electric busses, and the government has started phasing out its use of diesel-powered vehicles and replacing them with e-vehicles.

In Holetown on Barbados’ west coast, a small town famous for its white sand beaches, Roofs to Reefs crews have created coastal protection barriers and installed a drainage system, in response to years of flooding.

During one of those floods, “My son almost floated away in a car,” said Jeffrey Jones, 64, a computer technician who lives in Holetown. But these days, he told AQ, “things are going smoothly.”