SÃO PAULO – Regional climate change policymakers and analysts are still processing the ideas exchanged in the Amazon Dialogues and the Amazon Summit, two events organized earlier this month by Brazil to discuss the future of rainforest shared by nine countries. With lots said and formally declared, the key issue now boils down to converting words into meaningful action.

Brazil’s choice to hold the two events consecutively, and not concurrently, as it happens at the United Nations level, was done by design. With the Amazon Dialogues, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva brought back a foreign policy based on social participation with consensus-driven tactics. Civil society organizations, social movements, academics, the private sector and government agencies had the opportunity to weigh in on the idea of a ‘new’ forest-based economy and a socio-political territory for the Amazon, a sort of potential powerhouse for this natural biome.

While the talks elicited some well-deserved criticism from civil society participants, the achievements of Amazon Summit are clear. It achieved its main goal: to bring together leaders from the Pan-Amazon region to articulate a common agenda for sustainable development based on combating deforestation and fighting social and economic inequalities. Key issues, such as urban economic development, entrepreneurship, science, and technology, also received a fair amount of attention.

The final declaration of the event introduced relevant and unprecedented elements. Acknowledging the need for collaborative action to prevent the Amazon from reaching a point of no return was pivotal. Giving an institutional boost to the eight-nation Amazon Treaty Cooperation Organization (OTCA) was needed, as the accord has been underutilized for more than a decade as a mechanism for regional cooperation on Amazon-related issues.

Still, some gaps were also evident and the final document, the Belém Declaration, did not make a commitment to zero deforestation in the Amazon due to lack of consensus, nor did it explicitly call for the end of oil exploration in the region. Indigenous groups, activists and experts rightfully argue that without both commitments, a climate declaration is inherently fragile.

The oil issue

Beneath the successful diplomatic outcome, divergences and challenges remain. First and foremost is the case of oil. Colombian President Gustavo Petro’s call to end hydrocarbon exploration in the Amazon was resisted by Brazil, the region’s largest oil producer, and others.

The expectations that eight governments would commit to the cessation of oil exploration in the Amazon were crushed as soon as the Summit’s final document was released to the public. Understandably, the lack of a commitment by political leaders to end the exploration of oil in the Amazon irritated civil society organizations, especially because the oil industry topic was omnipresent in all the plenary sessions and debates throughout the Amazon Dialogues conference.

The diverging stances of Colombia and Brazil on ending the exploration of fossil fuels in the Amazon demonstrates that countries in Latin America – and developing countries more generally – assign considerably different weights to the phasing-out of fossil fuels in their approaches to an energy transition.

Despite calls from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the International Energy Agency (IEA) to stop authorizing exploration of oil and gas reserves and take measures for a quick phasing-out of fossil fuels, should the world remain below the 1.5°C limit of the Paris Agreement, countries like Brazil are still reluctant to bend to the scientific evidence.

Last May, the Brazilian federal environmental agency, known as Ibama, denied a Petrobras application to explore oil in the mouth of the Amazon River. The rejection was mostly based on the weak environmental impact assessment studies presented by the state-owned energy company to explore oil in a highly sensitive ecosystem. Ibama also questioned the compatibility between the proposed project and Brazil’s nationally determined contribution (NDC) to the Paris Agreement.

Since the decision, Lula has not explicitly ruled out the possibility of extracting hydrocarbons under the seabed next to the Amazon rainforest; quite to the contrary, he has explicitly left this door open for the future. Having the protection of the Amazon as a top priority of Brazil’s foreign policy while simultaneously jeopardizing it with risky fossil fuel extraction projects is a source of tension.

A thorny deforestation

Unlike oil exploration, where Brazil blocked progress, the country host pushed its peers to agree on a deforestation–free Amazon by 2030, in line with its most recent climate commitments under the UN framework convention on climate change.

In the not-so-distant past Brazil has been widely praised for reducing deforestation in the Amazon by 80% in less than a decade (2005-2012). But since 2013, and more notably after 2018, deforestation rates in the Amazon rose. In just four years (2019-2022), the Brazilian Amazon rainforest lost over 35,000 square kilometers of native vegetation, as former President Jair Bolsonaro pushed to dismantle environmental and climate regulations.

Eradicating illegal and legal deforestation in the Amazon will not be easy. Illegal logging, mining and cattle-herding, as well as infrastructure expansion, have been the historical drivers. Now the growing influence of organized crime represents an additional challenge to tackle. In Venezuela, a state-sanctioned gold exploitation is ravaging vast parts of the Amazon amid lawlessness and uncontrolled mining techniques.

Lula has many ways to showcase his administration’s commitment to curb Amazon deforestation. Under the leadership of Marina Silva and Sonia Guajajara, Brazil’s ministers of environment and Indigenous peoples, respectively, important policies have been reinstated. The plan for the control and reduction of deforestation in the Amazon (PPCDAm), and the Climate Fund and the Amazon Fund, both key financing mechanisms, have been reactivated after being shut down during Bolsonaro’s administration.

Moreover, thanks to the nation’s Central Bank and Development Bank policies, Brazil’s financial system is controlling its lending practices, tightening loans to individuals and companies linked to illegal deforestation. And the environmental agencies, despite still facing significant constraints to their financial, human and political capacities, are gradually regaining their freedom to simply enforce the law.

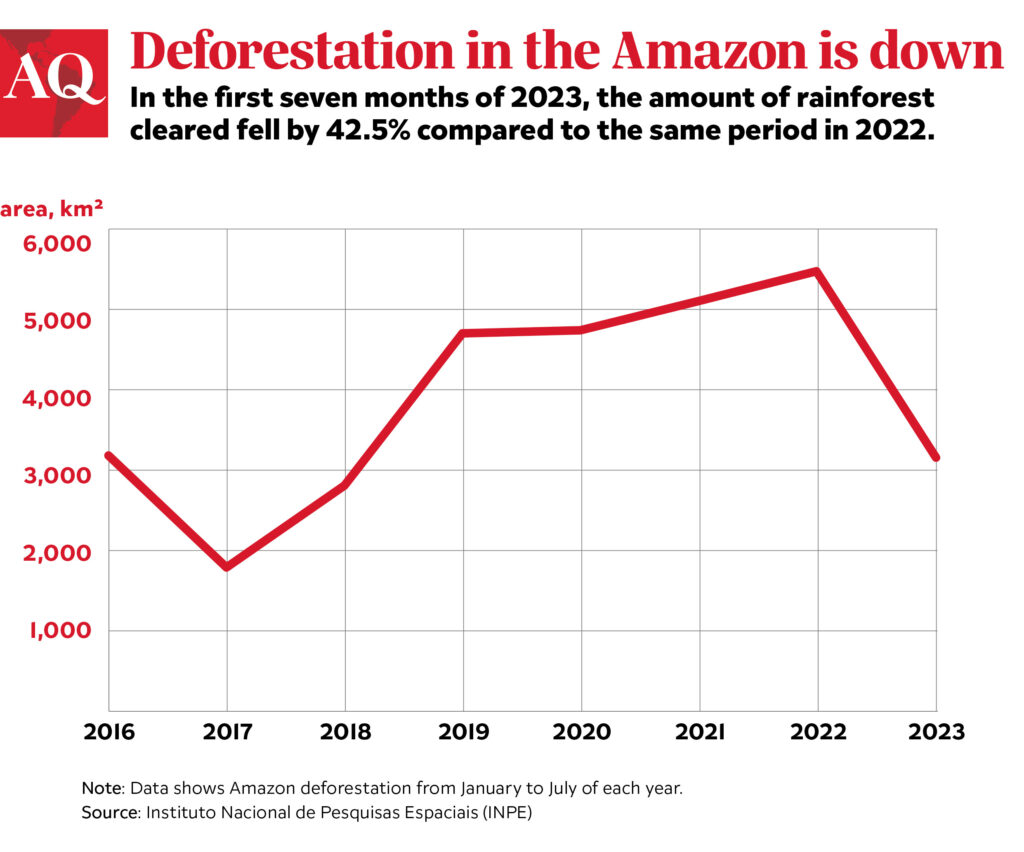

The results are evident. In August, Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research, known as INPE, confirmed that the Amazon’s deforestation declined 42.5% in the first seven months of 2023, compared to the same period in 2022.

Challenges on the horizon

With the climate emergency showing its unmerciful face everywhere in the world, there is no time to be wasted with political (and corporate) commitments devoid of real solutions. Against all these achievements and remaining challenges, implementation will measure the success achieved.

The Belém Declaration, with more than 100 paragraphs, now faces the test of realization. The OTCA and other existing or newly established forums resulting from the declaration need to be implemented. And the Amazonian Cities Forum, Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities Forum, and the Rural Women’s Forum are also expected to become a reality.

There are reasons to be guarded after Lula’s success with the two conferences. There were few announcements beyond those made by heads of state. The ambitious agenda for the Amazon demands investments, technologies, research and social development, which necessarily involve much more than state actors.