Murder is on the rise in Latin America. In Ecuador, after a large drop in homicides until 2016, murder rates spiked from 6 to 15 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2021 and to 26 in 2022. In Jamaica, homicide rates neared 50, while Honduras’s were estimated at 36 in 2022. (For reference, the U.S.’s homicide rate is 6.)

A chief factor behind this epidemic of armed violence is the diversion of, and illicit trafficking in, small arms and light weapons (SALW) across the region. These weapons are responsible for over 60% of homicides. But where do they come from—and how can the illegal traffic in weapons be stopped?

Latin America and the Caribbean is not a large market for the transfer of military conventional weapons. For the past five years, international arms transfers have decreased in South America, although Brazil saw a 48% increase in its imports from 2017 to 2022. Only a few countries in the region are producers of SALW and ammunition: Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Mexico.

And the region has stricter regulations for civilian possession of weapons than the United States. This is particularly the case for military-style weapons, like the AR-15 rifle that is often used by Mexican drug cartels. Most countries make licenses to purchase guns contingent on numerous requirements, including psychological evaluations, criminal background checks—and they also impose limits on the number and types of guns civilians can acquire.

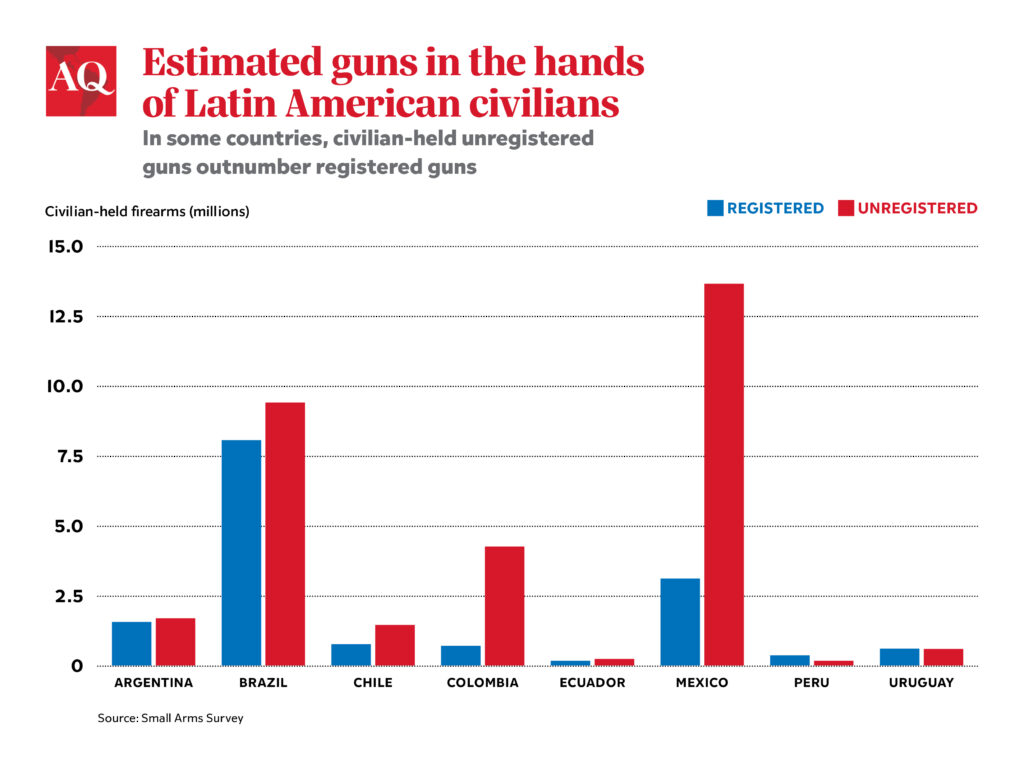

But despite these regulations, millions of weapons circulate in the region—with devastating effects. In 2018, it was estimated that over 60 million firearms were in hands of civilians in the region, both legally and illegally owned. In Bolivia, Colombia and Mexico, there are more unregistered weapons than registered ones. In Argentina and Brazil, the number of unregistered weapons is similar to the number of registered ones. Approximately 8.8 million SALW are also part of law enforcement and military holdings. It is harder to know the number of firearms owned by private security companies in the region, but a conservative number of 600,000 was estimated in 2015.

Illegal weapons in the region come from several sources. At the end of the civil wars in El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua, thousands of weapons were left unaccounted for, fueling a black market in Central America. Most analysts agree that a major source of trafficked weapons to the region is the United States, in particular to Mexico. An estimated 200,000 or more weapons are bought in the United States each year and trafficked to Mexico through “straw purchasers” who buy the weapons at arms stores or fairs. In the Caribbean, a recently published study shows that most of the firearms responsible for increasing levels of violence and higher homicides in countries like Jamaica and Haiti are trafficked from the United States via shipping companies and commercial airlines.

Diversion to the illegal market also occurs through forged end-user certificates with the complicity of corrupt officials. This was the case for the more than 7,000 AK-47s bought from Bulgaria by Colombia’s AUC in 1999—or the 3,000 AK-47s and ammunition bought by a Nicaraguan company and later diverted to Colombian paramilitary groups. More often, diversion occurs from official military and law enforcement stockpiles. Documented cases in Guatemala, El Salvador, Panama and Venezuela show that corruption in the military or security forces has played a big role in facilitating the diversion of legally acquired weapons to organized criminal groups operating in the region.

Finally, weapons diversion also occurs from private security companies which have flourished in recent years due to the deteriorating security situation in most countries in the region. According to data from Brazil’s Federal Police, more than 12,000 weapons were stolen or considered missing from private security companies’ stockpiles between 2017 and 2021.

A windfall for organized crime

The millions of illegal weapons circulating in the region and the persistent trafficking between countries and from the United States has allowed the activities of criminal organizations to expand, and it has made their activities even more violent. Drug trafficking, for example, is inevitably linked to the rising levels of armed violence in the region.

Yet the militarization of public security in Mexico and Brazil, for example, has not yielded positive results, as drug cartels and other criminal groups have only strengthened their firepower vis-à-vis the state. As drug trafficking organizations expand or move their operations to other countries, an increase in armed violence is likely to follow. This is the case for Ecuador and many nations in the Caribbean in recent years.

Firearms trafficking not only intensifies crime and violence: It affects economic development, political stability and the daily lives of millions of people in the region. It has been estimated that the direct costs of crime for 17 countries in the region in 2010-2014 averaged 3.0% of the region’s GDP—the equivalent to what the region spends annually on infrastructure. It is very likely that these costs would be higher today if the same variables would be measured again.

Government response

What are governments in Latin America and the Caribbean doing to control illicit trafficking in arms? Since the late 1990s, leaders in the region have sought to strengthen efforts to control and combat this phenomenon. Most states in the region have committed to numerous agreements, including the Inter-American Convention Against the Illicit Manufacturing of and Trafficking in Firearms, Ammunition, Explosives, and Other Related Materials (CIFTA) and more recently, the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT).

These agreements call for concrete action, like establishing national control systems, regulating firearms dealers and brokers, marking and tracing firearms, implementing diversion prevention measures and regional and international cooperation to investigate and prosecute those involved in illicit trafficking.

In most countries, regional and international organizations have supported the destruction of surplus weapons. In Argentina, 40,000 weapons were destroyed between 2020 and 2022, rounding out a total of more than 400,000 since 2000.

International cooperation between INTERPOL and law enforcement from across the region recently resulted in the detention of about 14,000 individuals and the seizure of 8,263 illicit firearms, as well as 305,000 rounds of ammunition. In 2021, in a similar operation 4,000 suspects were arrested and more than 200,000 illicit firearms, parts, components, and ammunition seized. Between 2016 and 2020, about 425,000 illicit weapons were seized across the region.

But despite efforts to increase the number of weapons seized annually, more needs to be done. And some governments are taking novel steps to address the problem.

In 2021, the Mexican government filed a lawsuit in a U.S. federal court against several American gun manufacturers, including Smith & Wesson, Colt, and Glock. The lawsuit seeks to hold these companies responsible for the role their weapons allegedly played in fueling the ongoing drug violence in Mexico. Though the case was dismissed in 2022, Mexico has recently filed an appeal. CARICOM states have also taken steps to address the illicit trafficking in weapons by proposing to ban the public use of assault weapons.

There are other measures governments can—and should—take to tackle weapons trafficking. Improving stockpile security, conducting more arms destructions, enforcing marking and tracing and updating record-keeping systems are a few. Exchanging information at relevant regional and international fora and improving border controls to stop weapons smuggling could also help. But without a comprehensive approach to the problem that reduces the overall demand for weapons, our region will likely continue being the most violent in the world.

Subscribe to The Americas Quarterly Podcast on Apple, Spotify, Google and other platforms

—

Solmirano is an international security and arms control expert with over 2 decades of experience in the field. She currently leads the ATT Monitor project at Control Arms. Her opinions do not necessarily represent those of the organization.