As World War II transformed Europe into a genocidal hell, the continent’s Jews were desperate to flee to any country willing to provide them refuge—even far-flung Bolivia. In the new book Escape a los Andes, journalist Raúl Peñaranda and historian Robert Brockmann tell the long-buried story of how thanks to the efforts of mining magnate Moritz “Mauricio” Hochschild, an estimated 12,000 Jews found safety in the altiplano.

There’s a phrase in the Torah about Jews being “strangers in a strange land.” For European Jews, there could perhaps be no stranger land than Bolivia. Not only was the environment of the highlands utterly foreign, but the country was poor, underdeveloped, freshly defeated in the Chaco War (1932–35) and experiencing a leprosy epidemic. “The country seemed struck by a Biblical calamity,” the book explains.

Escape a los Andes

by Raúl Peñaranda and Robert Brockmann

Aguilar

Paperback

516 pages

This was why, when Bolivia was suggested as a safe country for Jewish refugees at a series of international conferences in the late 1930s, most of the world scoffed. An undercurrent of doom runs through the narrative: while world leaders bickered and proposed unlikely destinations like Guyana, Madagascar and Alaska, the Nazi project marched forward.

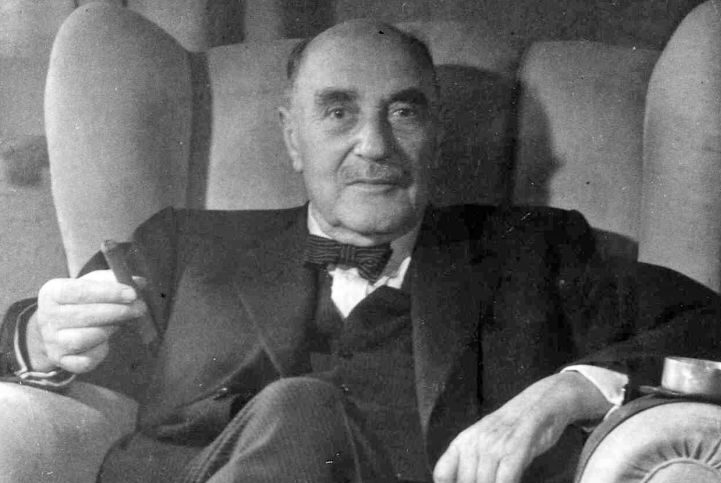

Thankfully, one man successfully championed the case for Bolivia. In the book, Hochschild is nicknamed “the Bolivian Schindler,” after the famed German factory owner who saved hundreds of Jewish lives. Like Schindler, the German-born Hochschild was a titan of industry, having built a tin empire in South America in the 1920s. But Hochschild, unlike Schindler, was himself Jewish. Upon Hitler’s rise, he lost his German citizenship due to his ethnicity—and, from that point, gradually became more dedicated to using his largesse to promote a Bolivian solution to the Jewish refugee crisis.

Hochschild found an ally in the ironically named Bolivian President Germán Busch (1937–39). Busch instructed Hochschild to present him with a plan to “turn Bolivia into an orchard” for Jews, and Hochschild delivered, arguing Bolivia could benefit economically from migration. By 1939, the country opened its doors fully to both Jewish refugees and other groups persecuted by the Nazis.

Escape a los Andes is many things: Holocaust synopsis, Hochschild biography, Bolivian political thriller, mining manual, refugee travelogue. But what it is not (besides concise) is a story of uplifting hope. Readers looking to find clean-cut heroes and uncomplicated narratives should look elsewhere. Consider President Busch: While sympathetic to the plight of the Jews, he was also an admirer of Hitler’s totalitarian political project. And, Hochschild, a Jewish savior, was also a ruthless extractivist who often overlooked the human costs of the fortune that he used to help relocate thousands of refugees.

By the end of the war, Hochschild’s business practices and Jewish advocacy made him a scapegoat. In rapid succession, he was both arrested as a political prisoner and kidnapped. It’s a familiar refrain: a Jew betrayed by the place he once considered his adopted homeland. Shortly after the end of the war Hochschild, along with most of the country’s Jewish population, left Bolivia, facing anti-Semitism, a volatile political climate, and a lack of opportunities.

When it comes to Latin America’s role in the Holocaust, the world has long fixated on the region’s involvement in the relocation of Nazis through the Ratline system. It’s refreshing to read a new account that provides a counterpoint, and the authors must be commended for their archival brilliance.

But in celebrating Hochschild, Escape a los Andes leaves a question mark for the reader over how to think about Bolivia’s role during and after the Holocaust. What to make of a country that was one of the world’s few righteous nations—but whose story exemplifies in many ways how the world failed the Jewish people again and again in the 20th century? One must read with both admiration and horror.

—

Harrison is editorial manager at AS/COA Online