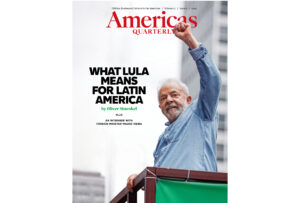

This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Lula and Latin America

Mexico City — President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s six-year term will come to an end in 2024. Whoever takes his place will face a range of foreign policy challenges shaped in large part by his reluctance to dwell on foreign relations.

Famously focused on domestic issues, López Obrador has traveled only to the U.S., Central America and Cuba as president, eschewing state visits to the rest of the globe. Mexico may have had a unique opportunity to step up as an international leader as former President Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil withdrew his country from the regional and world stage. But it seems that no one in López Obrador’s inner circle was interested.

Mexico’s most important foreign relationships under the current administration—after the U.S., undoubtedly its most important partner—have been with countries in Central America. This is not, however, a result of sustained, innovative diplomacy. On the contrary, López Obrador endeavored to reinvigorate these relationships—long undervalued in Mexico—mainly to cooperate with the U.S. on reducing migration.

Even this blinkered attention, though, has been more meaningful than that afforded to South America, limited largely to López Obrador’s dreamy rhetoric on the Bolivarian fantasy of deep Latin American integration. Sometimes, he talks about building a union like the European Union. At other times, he calls for the integration of the entire hemisphere with the U.S. and Canada. But, unsurprisingly, the content of such proposals has been unfocused and contradictory.

The weakness of Mexico’s relationship with the rest of Latin America comes into sharp relief in the lack of support its proposals receive in regional forums. At the Inter-American Development Bank, Mexico’s candidate to lead the bank after the departure of Mauricio Claver-Carone received minimal backing—a result due in part to Mexico’s clumsy handling of its nomination. Meanwhile, at the Organization of American States (OAS), Mexico remains quite alone in its efforts to replace Secretary General Luis Almagro and even more so in its aim, never well articulated, to dissolve the institution entirely.

The Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) is the only regional forum in which Mexico has managed to show some leadership, first to ensure that the forum wouldn’t perish, and then to orchestrate significant collaboration in response to the pandemic. López Obrador has failed, however, to make Mexico more internationally relevant through this forum, a key part of his plan to sap the influence of the OAS.

Even so, observers are quick to speculate that the return of left-wing Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva as president of Brazil will result in reinvigorated political and economic ties with Mexico. But conditions are simply not right for meaningful progress on this front. First, the two leaders are on different political schedules. Lula is just beginning his term, while López Obrador is nearing the end of his presidency and is therefore turning his attention even more fully to domestic politics.

Second, their personalities are markedly different. Lula has always searched out the international spotlight and opportunities for global leadership, and Brazil’s geopolitics facilitate both. It shares borders with 10 nations and has staked out a prominent role among large developing countries, most notably through the BRICS framework. Finally, Brazil’s most important economic relationship is with China, not the U.S. Indeed, Brazil’s political elites, some very close to Lula, seem to share the conviction that “Mexico is part of the north.”

Greater collaboration between Mexico and Brazil would be a welcome change and would strengthen the position of Latin America on the world stage. But, given Mexico’s track record of insularity under López Obrador, this goal—like so many others—will remain an admirable idea whose time has not yet come.

Even Mexico’s relationship with the U.S., replete with opportunity, is beset by conflict. Sometimes that conflict is avoidable, such as when López Obrador chose last year not to attend the Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles over the Biden administration’s refusal to invite leaders from Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua.

Now, sadly, this year’s cartel murder and kidnapping of U.S. citizens in Matamoros and the ongoing crisis of fentanyl overdose deaths in the U.S. are dominating discussions about the U.S.-Mexico relationship, even on the heels of Tesla’s announcement that it would build a gigantic factory in Monterrey. Such tensions have always existed, but the relationship is especially fraught as the 2024 elections in both countries near; it is increasingly caught up in domestic partisan disputes on both sides of the border.

In the U.S., President Biden knows that any apparent failure to stem irregular immigration could cost his party the White House. Meanwhile, in Mexico, López Obrador stands ever ready to play on nationalist sentiment by accusing U.S. media, legislators and agencies of imperious interventionism, especially given recent calls by some of those legislators for U.S. military action against the cartels.

Given the political primacy in the U.S. of these kinds of issues, it is extremely unlikely that the Biden administration—or any other—will weigh in meaningfully on López Obrador’s controversial reforms of Mexico’s elections authority that undermine its independence. It is far more likely that the U.S. will look the other way, prioritizing other issues; after all, the history of U.S. action to support democracy in Latin America is largely a sad saga of failure. Opponents of the reforms should not cling to the hope that the U.S.—or the international community more broadly—will be able to blunt them.

The U.S. is, however, eager to engage on the much-heralded process of nearshoring to Mexico. The opportunities provided by China’s faltering role in U.S. and European supply chains are enormous, and it would be a grave error for Mexico not to do everything possible to capitalize on them. And yet, Mexico has failed to take certain basic steps that would encourage potential benefits to materialize. For example, it still lacks an industrial policy and legal framework to clarify its new goals and provide certainty to potential new investors. This is especially important given that Mexico’s deficient communications, energy and water infrastructure, along with rampant insecurity, also pose serious impediments.

The best chance for meaningful, creative and effective dialogue remains the creation of a binational technical commission staffed with experts and technocrats. The commission could craft proposals for feasible, cooperation-oriented action to manage urgent problems like drug trafficking, migration and arms trafficking from the U.S. to Mexico.

But such a commission has yet to materialize, like so many other obvious opportunities. For now, far from a leader on the international stage, Mexico will remain a cautionary tale of how an insular foreign policy results in untapped potential.

—

Pellicer is a political analyst, professor and former Mexican diplomat. She currently teaches at the Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México (ITAM) and is a columnist for Proceso magazine.