| Leer en español |

For decades, Salvadorans have faced egregious gang violence and successive governments unable or unwilling to ensure safety in people’s everyday lives. No wonder many support President Nayib Bukele when, during his administration, the rates of homicide and extortion have apparently decreased significantly. But neither Bukele, nor his followers at home, nor his growing fan club in the region are willing to seriously debate the price of his policies, whether they are sustainable, and the consequences of dismantling the country’s democratic institutions.

March 27 is the one-year anniversary of El Salvador’s state of emergency, initially put in place for 30 days to address a spike in gang violence. Since then, police and soldiers have arrested more than 65,000 people, including hundreds of children.

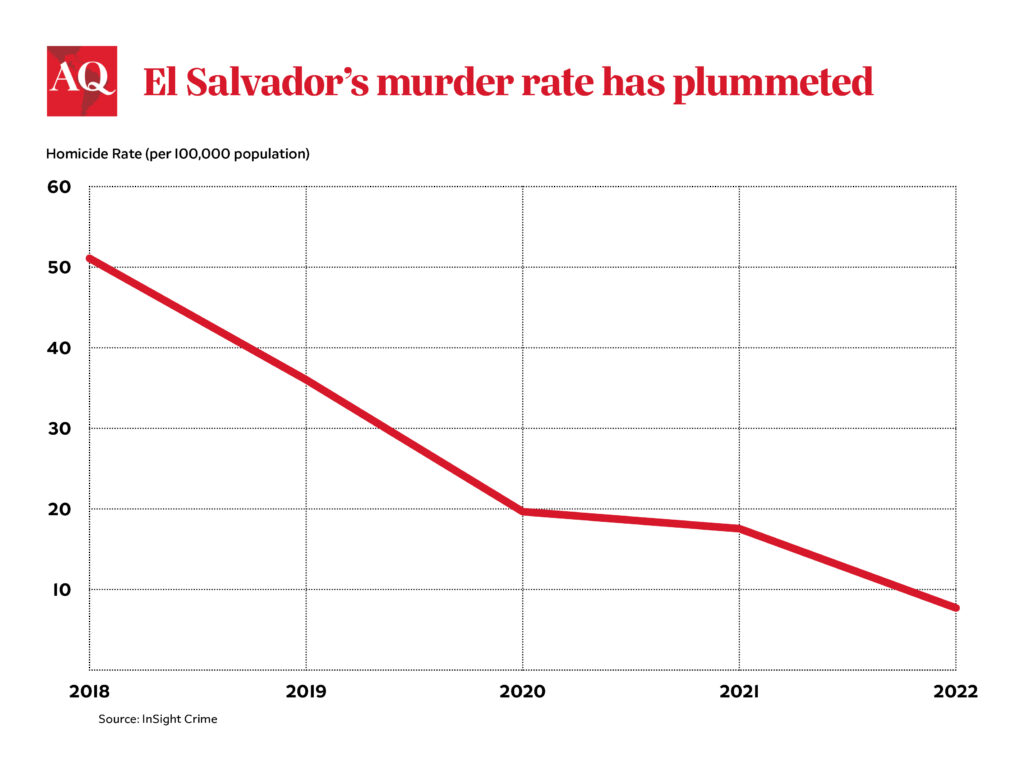

Extortion, which entrenched gangs’ territorial control, has reportedly decreased. Homicides, which have been decreasing since 2015, have fallen further, with official figures indicating a rate of 7.8 homicides per 100,000 people in 2022. Although changes in the ways killings are counted make it harder to estimate the true extent of the reduction, few people doubt that the rate of killings in El Salvador, once among the highest in the world, has diminished.

But the way that President Bukele carries out his security policies features widespread violations of people’s rights. Many Salvadorans with no connections to gangs have been arrested, especially in low-income neighborhoods. Our research shows that some people detained have been tortured, dozens have died in custody, and thousands have been subjected to abusive legal proceedings without due process. People arrested have been placed in incommunicado detention. The authorities cause the families of people swept up this way great suffering by denying them information about a detainee’s whereabouts, which constitutes an enforced disappearance.

Bukele’s dismantling of democratic institutions since he took office in 2019 enabled him to carry out his abusive public safety policies. He has purged the Supreme Court and replaced the attorney general with an ally of his. Bukele has announced he will seek re-election in 2024, relying on a ruling by government allies in the Constitutional Chamber, which departed from longstanding jurisprudence forbidding immediate re-election.

Latin America has already seen the negative impact of his approach to governing. Examples from recent history, including in Venezuela under Hugo Chávez and Peru under Alberto Fujimori, show how initially highly popular leaders can dismantle democratic safeguards, central to human rights and the rule of law, in ways that are hard to rebuild.

Democratic leaders from across the ideological spectrum should speak up against Bukele’s repressive policies. Soon.

Leaders in the region may have been hesitant to speak up for several reasons. One is Bukele’s popularity. Another is that many leaders are struggling to effectively address violence and organized crime in their countries. Criticizing someone for policies that appear to provide a popular and seemingly easy “fix” to one of Latin America’s key concerns, and proposing an alternative that addresses complex root causes of violence, may seem politically unattractive.

But if leaders don’t speak out, it may well be impossible to curb the dangerous democratic backsliding in the region, of which Bukele is a blunt example.

Multilateral pressure has been shown to be effective in curbing Bukele’s authoritarian tendencies. In November 2021, for example, a coordinated response helped halt the approval of a “foreign agents” bill that would have severely undermined the work of civil society groups and journalists. Among those raising the issue were the U.S. and the EU. The German Embassy threatened to withdraw its support for humanitarian programs in the country.

Now, members of the Central American Bank for Economic Integration (CABEI), such as Colombia, Argentina, Spain and Costa Rica, should add adequate safeguards on all its loans to ensure that funds are not used to commit abuses and that they enhance Salvadorans’ security. These countries should request the suspension of all existing loans to government entities directly involved in widespread abuses in El Salvador, including the National Civil Police, Defense Ministry, prison system and the Attorney General’s Office, until such safeguards are in place.

The Biden administration has included 25 Salvadorans—including President Bukele’s legal adviser, his Cabinet chief and the penitentiary system’s head—on the “Engel List” of people identified as having engaged in “significant corruption” or acts that “undermine democratic processes.” These sanctions have made it harder for institutions involved in abuses, such as the prison system, to get foreign funding. In February, the U.S. Department of Justice unsealed charges against 13 gang leaders from MS-13, indicating that the Bukele government had negotiated benefits for gangs in exchange for fewer homicides and electoral support.

Other actors globally should follow suit. It is, however, also essential to show that democratic institutions are not an obstacle, but rather a vehicle, to address the needs of the people—ranging from insecurity to inequality and poverty.

Foreign governments should press, privately and publicly, to strengthen judicial independence. They should also increase support to Salvadoran independent journalists and civil society groups, which are virtually the sole check on the president’s abuse of power.

Checks and balances are crucial to prevent corruption and ensure that the law is applied equally to all. Without due process, judicial authorities won’t be able to determine if a detainee has in fact committed a crime or seriously assess each of the thousands of people detained under the state of emergency. Neither justice for victims of gang violence nor the protection of the rights of detainees will be achieved.

These checks exist precisely to protect rights—and Salvadorans who blindly support Bukele today will most likely think differently if they or their loved ones end up being victims of state abuse and have nowhere to turn. When there are no rules, anyone’s rights can be violated.

Latin America and the Caribbean has the highest regional annual homicide rate in the world, at 21 per 100,000 people in 2020. Many will continue to support Bukele-like ideas as long as violence and organized crime remain unaddressed.

They should know, though, that in El Salvador, both obscure negotiations with gangs and iron-fisted security policies have failed to address gang violence in a sustainable manner. When Bukele’s predecessors negotiated with gangs without effectively dismantling them, they achieved a short reduction of killings, followed by long-term surges in gang violence. Previous massive arrest strategies were also counterproductive, allowing gang members to increase recruitment in prisons, reinforce their internal structures and use detention centers as bases.

There’s little reason to think that Bukele, who has both negotiated with gangs and ordered massive arrests, will achieve a different outcome in the medium or long term.

Instead, the Biden administration, the EU and Latin American governments should promote—in El Salvador and at home—rights-respecting strategies to tackle the root causes of criminality, including high levels of poverty and social exclusion, and push for strategic criminal prosecutions focused on violent abuses, particularly those committed by senior gang members or chronic abusers.

Leaders need to show that democratic institutions can make people safe.