CARACAS — Political unrest is posing a threat to governance and stability across Latin America—and its roots can be partly traced to extreme inequality.

During most of the first two decades of this century, solid economic growth rates in Latin America and the Caribbean helped improve social indicators. However, gains have stagnated since 2015, when growth started to falter with the end of the commodity boom. The pandemic only made things worse, increasing inequality and setting poverty back to levels unseen in a decade (32.8%, according to ECLAC).

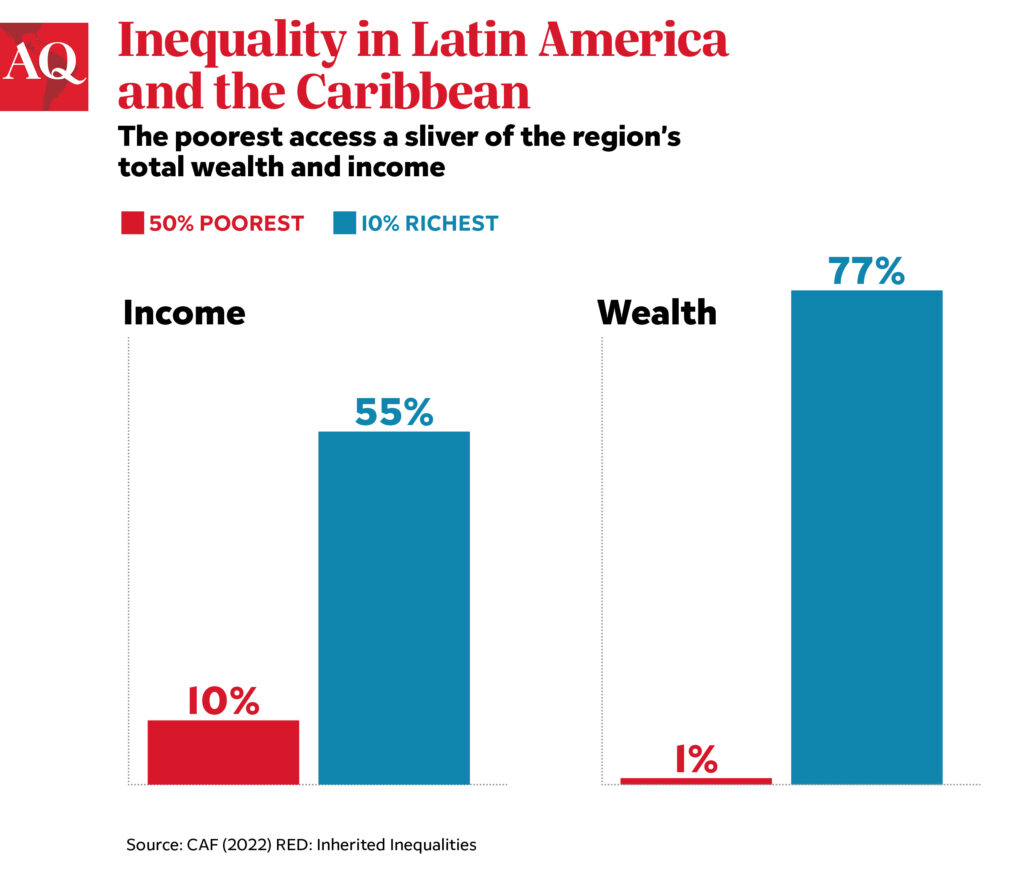

This further deepened the region’s income gap. In inequality metrics such as the World Bank’s Gini coefficient, the region consistently underperforms the rest of the world. The numbers are sobering: The poorest 50% of the population earns just 10% of total income, while the wealthiest 10% earns 55%, according to the World Inequality Report.

The CAF development bank’s latest flagship Report on Economic Development, RED 2022: Inherited inequities, shows how this reality perpetuates itself. Social mobility must improve in order to reduce inequality, but high inequality prevents greater social mobility. Novel evidence shows that, in Latin America and the Caribbean, mechanisms like human capital accumulation (for example, education and health), asset accumulation and labor opportunities strongly favor wealthy families.

When your chances of progress are primarily determined by family background rather than individual effort and merit, the cradle becomes a lottery marking your future. And perpetuating inequalities affects talent allocation, growth, social cohesion—and political stability.

Social policies have so far been unable to overcome this reality, despite recent progress. Many children in the region exceed their parents’ educational achievements, as years of schooling steadily increased over the past century. While over 80% of the children born in the first decade of the 20th century did not complete elementary school, that fraction was less than 5% by the dawn of this century.

However, the gap itself has hardly changed. Only one in ten children of non-college-educated parents obtain a college degree by 24 or 25 years of age. That fraction is almost 50% for children with a parent who graduated from college. The pandemic only made prospects worse. The region had the most extended school closures, and poor families were left behind by a large gap in internet access and connectivity.

Even if younger generations’ academic achievements have improved with respect to their parents’, labor market opportunities have not. The children of parents employed in high-skilled jobs are almost six times more likely to land such jobs than are the children of parents employed in low-skilled occupations. This replication mechanism also includes family networks and aspirations as well as discrimination against certain groups in the labor markets.

Low educational and occupational mobility contributes to reproducing income disparities from generation to generation. In Latin America, you are likely to end up where your parents are on the income distribution ladder. In fact, the report indicates that the region has the greatest immobility in income in the world.

Another mechanism that perpetuates inequality is the high level of wealth concentration that largely persists across generations in Latin America and Caribbean nations. Certain mechanisms tie the quality and quantity of assets accumulated by parents to those we find in the hands of their children. The report highlights the following such mechanisms: asset composition; financial inclusion gaps, in access to banking or insurance, for example; the greater vulnerability of the assets of disadvantaged households; and the difficulty these disadvantaged households have in acquiring assets. The lack of access to proper insurance mechanisms is especially important in a region prone to economic shocks—as well as the increasing risks of climate shocks that threaten to destroy housing, the main asset of most families in the region.

Listen to this episode and subscribe to The Americas Quarterly Podcast on Apple, Spotify and Google

It can be done

News is better regarding health. The transmission of poor health conditions from mothers to babies and young children has steadily declined in the region, partly due to maternal and child health coverage improvements. And there are several policy options that can address other areas and help break the cycle of low social mobility and inequality in Latin America and in the Caribbean, such as skills training; facilitating access to jobs through employment services; more robust labor regulations and social safety nets; progressive taxation; and greater financial inclusion, to name a few.

Some of these reforms can be politically challenging to implement. Attempts to enact tax reforms to finance social spending, reduce regressive energy subsidies, or change labor regulations have in recent years elicited social protests throughout the region, forcing authorities to back out or water down proposals. However, there are glimpses of hope. Background work for the RED 2022 suggests that, when confronted with the blunt reality that social mobility in the region is far worse than they thought, individuals seemed more willing to accept more progressive taxation to improve opportunities, especially in education.

Policies should focus on implementing interventions at as early an age as possible. Initiatives should address issues before pregnancy and continue during early infancy, childhood, adolescence and the transition to adulthood.

The region needs to level the playfield for the new generations so that “the cradle” weighs less on their future opportunities and well-being. Equity is not just a humanitarian imperative. Inequality prevents efficient allocation of talent, capping efficiency and economic growth. In turn, low growth is tantamount to tepid job creation and lost opportunities. This is a vicious cycle that ultimately leads to social and political unrest. There is no silver bullet, and social consensus will be required to advance necessary reforms.

Unless we address inequality, growth—and stability—may remain elusive.

—

Arreaza Coll is Knowledge Manager (Acting) and Director of Macroeconomic Studies at CAF, Development Bank of Latin America. She coordinates the team of country and research economists. Arreaza was an Assistant Professor at the Department of Economics of Universidad Católica Andrés Bello in Caracas and previously worked at the Research Department of the Central Bank of Venezuela. She received her BA in Economics at Universidad Católica Andrés Bello in Caracas and her PhD in Economics at Brown University.