QUITO — With his approval rate down below 20% and his pro-growth agenda largely stalled in the face of a hostile Congress and an ongoing security crisis, Ecuadorian President Guillermo Lasso is looking for ways to regain the initiative.

One is putting issues directly to the people—something Lasso is planning to do with an eight-question referendum, which is set for February 5. Another avenue is trade policy, with accession to the Pacific Alliance, a free-trade bloc founded in 2011 by Mexico, Colombia, Peru and Chile, being the most immediate opportunity for Ecuador.

Lasso’s referendum questions deal with security policy—a key public concern—by legalizing the extradition of Ecuadorians involved in international criminal organizations and providing more institutional independence to the General Prosecutor office. Another set of questions seeks to drive political reform in three ways: limiting the responsibilities of the powerful Citizens’ Participation Council and changing the way its members are appointed; promoting transparency regarding the membership base of political organizations; and most conspicuously, reducing the number of lawmakers in Congress. There are also questions on environmental policy. If approved, the referendum will automatically amend the Constitution.

The questions have been carefully designed to generate the least resistance from the public and secure a political win that can be presented as a renewed mandate for the Lasso administration, providing him with some political breathing room. But even if successful, the referendum will not significantly change current political dynamics between a weak government and an increasingly destabilizing opposition in Congress. And if the process turns into a referendum on a very unpopular government—which is what most of the opposition is seeking to make it—the Lasso government will come out even weaker, exposed to renewed efforts aimed at forcing early elections next year.

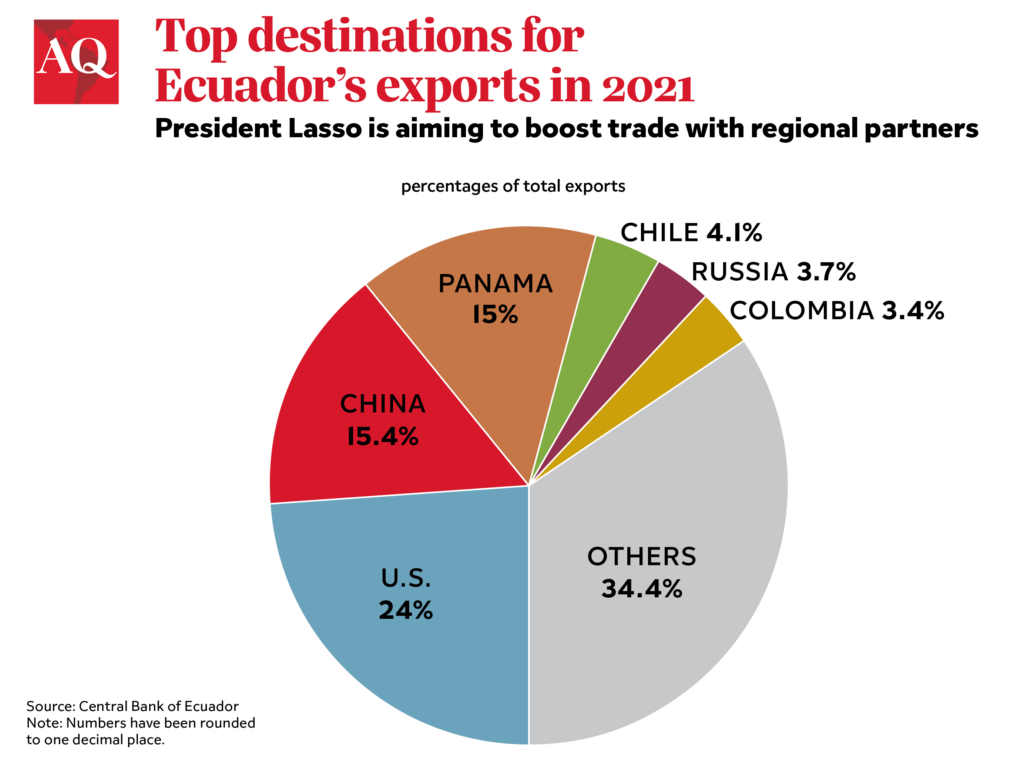

Lasso’s pro-trade agenda is a marked shift from the previous two decades in Ecuador, during which tariffs and trade restrictions ramped up, making Ecuador the only country in the Pacific coast of the Americas with no free trade agreement with the U.S., and the only one on the Pacific coast of South America that is not part of the Pacific Alliance.

But global sentiment around free trade has significantly soured in recent years and the U.S. government has little to offer in that area to Ecuador, now one of its closest allies in the region, besides cooperation on trade rules and transparency. Free trade within Latin America also faces significant challenges in a region mostly back in the hands of left-wing governments with a protectionist streak: Since 2018, left-wing governments have been elected in every member country of the Pacific Alliance.

A free-trade deal with Mexico, a prerequisite to join the Pacific Alliance, has bogged down due to President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s strong resistance to offer wide market access for Ecuadorian shrimp and bananas—two of the country’s key exports—in order to protect local producers. Ecuadorian authorities were anticipating a quota-based agreement with Mexico for access for these products before the end of the year, but admitted last week that terms offered by the López Obrador administration are still unacceptable.

That is holding up accession to the Pacific Alliance, whose four members together represent 41% of Latin America’s GDP and a market of over 220 million people, something Ecuadorian authorities are eagerly seeking. Joining the Pacific Alliance would be a major win for Lasso and would go a long way toward boosting the reputation of a government whose economic liberalization agenda has either stalled or, in some instances, gone into reverse. Such a development would be especially welcomed by local business elites who have strongly supported Lasso but are growing increasingly frustrated by lack of progress on his economic liberalization agenda.

In the long run, Ecuador’s ascension to the Pacific Alliance would lock in orthodox trade and investment policies, badly needed in a country that wants to signal a clear break from the protectionist policies of the past 15 years—and might also help hedge against the likely return of populist governments down the road. It will also continue to steer Ecuador away from other regional political alliances like ALBA or UNASUR, which have been in decline for years but could see a path to reactivation with new left-wing populist governments, most notably in Brazil, sweeping over the region.

Ecuador finds itself swimming against the current by actively seeking to open its economy and promote free trade, right at a time when such policies have become less fashionable in Latin America and around the world. But its forward momentum on trade depends on Lasso’s ability to push the agenda forward—something which hangs in part on the result in February’s referendum.

—

Hurtado is founder and president of PRóFITAS, a leading political risk consultancy based in Quito.