The United States is giving the countries of the Northern Triangle high level diplomatic attention at a critical time. It may not be enough.

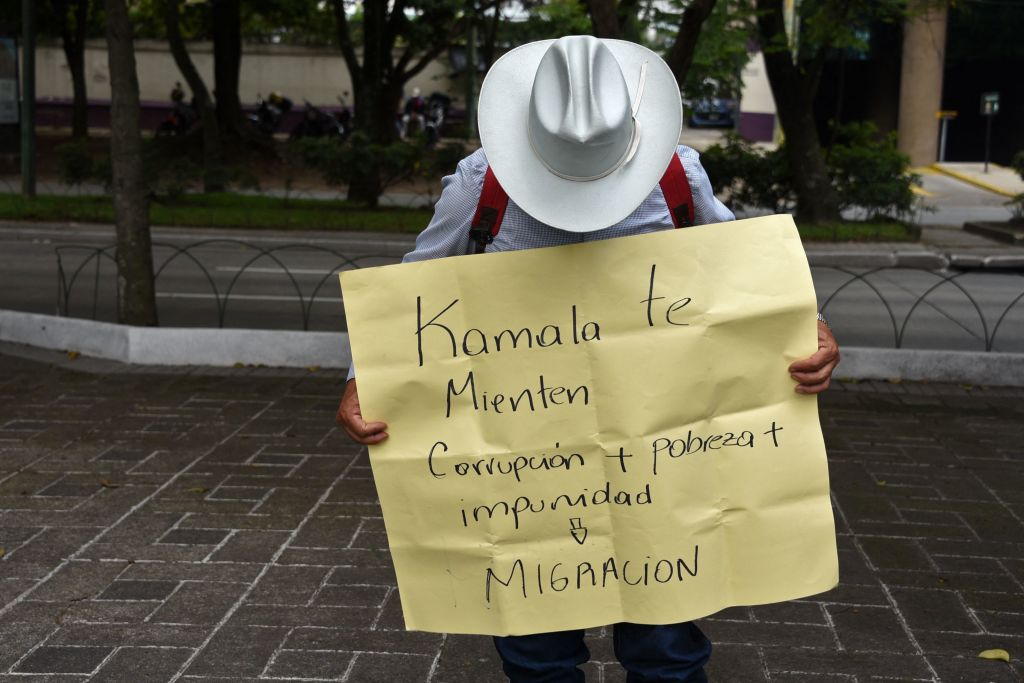

In El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, the judiciary is under assault by a cabal of corrupt national leaders, human rights violators, drug dealers and influential economic sectors. U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris, who visited Mexico and Guatemala last week, has called corruption a “root cause” of the migration crisis and USAID Administrator Samantha Power, who is currently travelling in the region, says that corruption is a “key area of vulnerability” of repressive regimes.

She’s right. Corruption by kleptocratic leaders decimates governments’ capacity to provide quality healthcare, education and infrastructure. Kleptocrats also perpetrate human rights abuses against activists and citizens who inevitably protest the theft of state resources. Recognizing corruption’s multifaceted threats, President Joe Biden issued a memorandum in early June defining the fight against corruption as a core U.S. national security interest.

Unfortunately, renewed U.S. diplomacy alone is insufficient to address the rampant corruption in the Northern Triangle and beyond. If the Biden Administration wants to promote good governance and fight corruption abroad, it should consider establishing supranational mechanisms to defend the rule of law. More than one hundred world leaders have signed a declaration in support of one such proposal: the creation of an International Anti-Corruption Court (IACC) that would prosecute crooked leaders when national governments are either unable or unwilling to do so.

The situation is dire – and getting worse. In 2020, all three Northern Triangle countries and their neighbor Nicaragua ranked near the bottom of Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index and the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index. In AS/COA and Control Risks’ 2021 Capacity to Combat Corruption Index, Guatemala’s score declined 5%, falling to 13th place out of 15 countries. All four countries performed worse than Afghanistan on the Rule of Law Index’s criminal justice assessment. True, Guatemala and El Salvador performed somewhat better than their neighbors by the metric of constraint on government power, including the independence of the judiciary. Still, ranking 69th and 77th respectively out of the 128 countries, they were hardly pinnacles of success in 2020. Recent events will surely see them slip even further in 2021.

On May 1, its first day in session, the Salvadoran parliament – controlled by allies of President Nayib Bukele – arbitrarily removed five Supreme Court Justices and the Attorney General. The move echoed troubling developments in neighboring Guatemala, where the Congress refused to swear in the graft busting Magistrate Gloria Porras in April after she was re-elected to a second five-year term on the Constitutional Court, even as the same lawmakers approved the seating of three magistrates who raised corruption red flags.

The crumbling of anti-corruption mechanisms in the Northern Triangle has erased the hard-fought progress exemplified by the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG). The unique United Nations-backed institution provided independent support to the Public Prosecutor’s Office, leading to the convictions of dozens of the country’s most influential figures. That is until President Jimmy Morales took office. Despite having been elected in 2015 on promises to tackle corruption, Morales soon turned on the anti graft body and refused to renew its mandate, forcing it to shut down for good in 2019. CICIG’s surviving institutional legacy, Guatemala’s Special Prosecutor Against Impunity (FECI), is the target of constant attacks by groups seeking impunity at any cost — not least by sitting president Alejandro Giammattei ahead of Vice President Harris’s visit.

Honduras briefly tried its own version of a special justice panel. In 2016, protests sparked by the embezzlement of $335 million at the Honduran medical care and pensions agency and the subsequent deaths of approximately 3,000 patients due to the lack of proper care led to the formation of the heralded, if comparatively limited, Mission to Support the Fight Against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MACCIH). However, like CICIG, it too faced fierce pushback from Honduran kleptocrats and was disbanded by President Juan Orlando Hernandez in January 2020.

The same story is now unfolding in El Salvador. After successfully campaigning on an anti-corruption platform in 2019, Bukele quickly established the International Commission Against Impunity in El Salvador ( CICIES). However, unlike the independent Guatemalan investigators, CICIES answered to the Salvadoran executive. Although the Secretary General of the Organization of the American States nominated the body’s chief, Bukele had the last word on the appointment, and the panel had no mandate to conduct independent investigations or prosecute cases. On June 4, Bukele and his Attorney General announced El Salvador’s decision to break its agreement with CICIES. The move dismayed the U.S. government, which had donated $2 million to CICIES in April.

For all their shortcomings, CICIG, MACCIH and even CICIES were valuable experiments in strengthening accountability that could be emulated elsewhere. However, the fragility of all three institutions highlights the need for novel mechanisms that are not subject to the whims of venal presidents and the networks of kleptocrats that support them.

In the era of globalization, countries must comply with international standards of legality to earn the right to play on the field with other countries that do so. Otherwise, the ruling kleptocrats and their partners in crime should be sanctioned by the international community. While the International Criminal Court provides a mechanism to prosecute genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, it does not cover corruption.

An International Anti-Corruption Court (IACC), in turn, would fill the international anti-corruption enforcement gap and would bolster democracy by providing an impartial forum free from the distortions of geopolitics and domestic politics. It would also be uniquely suited to pierce the transnational networks of sketchy lawyers, bankers, real estate agents, accountants, and other service providers that facilitate grand corruption.

If the major financial centers that kleptocrats use to launder their stolen assets were to join the IACC, it would have extensive jurisdiction to recover, repatriate and repurpose the proceeds of corruption. That would give the anticorruption drive teeth, regardless of whether Bukele, Giammattei, Hernández and their like are willing to sign their countries up to the Court. When public pressure produces leadership changes in democracies as precarious as those of the Northern Triangle, there may yet be opportunities for them to join the Court, creating additional positive feedback loops that protect progress.

The scourge of grand corruption erodes the rule of law, fuels conflict, empowers human rights abuses by unaccountable governments, and denies struggling societies the resources needed to ensure access to education and healthcare. Addressing these problems in the Northern Triangle and beyond requires international innovations like an IACC that support the rule of law by punishing and deterring kleptocrats and their transnational networks of enablers.

—

Dr. Claudia Escobar Mejía is a former magistrate of the Court of Appeals of Guatemala. She is now a legal specialist on anti-corruption and international consultant in the justice sector, as well as a board member of Integrity Initiatives International.