MEXICO CITY – In the midst of social and economic unrest, the COVID-19 pandemic appears as an uninvited guest to an already crowded cocktail of Latin American headaches. Prevailing rates of poverty and an already weak economic outlook place the region in a fragile position to face the more than 100,000 cases confirmed through April. The virus has landed on fertile ground to expose and aggravate pre-existing social disparities and divisions that characterize much of Latin America.

The virus has highlighted some of the struggles that social minorities face in society, particularly women. The lockdown policies imposed to prevent its spread have resulted in heightened levels of gender-related domestic violence, with a surge in the numbers of complaints. Policies deciding who can leave their homes based on sex, have also shed a light on some of society’s uncomfortable expectations around women.

Before the pandemic, there’s no doubt that violence and discrimination against women was already a recurring problem. In 2019, nearly 60% of Bolivian women reported some sort of physical partner violence. In Mexico, official data recorded the murder of 10 women per day during 2018. The sheer dimension of this problem triggered a tsunami of protests all over the continent, which culminated in massive rallies organized on International Women’s Day in March. The mobilization was one of the largest in the region in recent years, particularly in Mexico, Argentina and Chile.

But no one was able to anticipate how much worse the already worrying situation for women and children was about to become due to the confined living conditions required by COVID-19 prevention measures.

In Argentina, emergency calls for domestic violence have increased by 25% since the beginning of the lockdown. In Mexico, the increase reached a staggering 60% while women’s shelters saw the doubling of applications due to domestic violence. In Chile, on the weekend of March 27-29 alone, emergency calls to the Violence Against Women Counseling Hotline increased by 70% when compared to the previous weekend. In Colombia, the increase reached 79% since the adoption of isolation measures while in Peru, 23 days after the state of emergency was declared, the hotline for violence against women received an average of 360 calls per day, 27 of which involved children.

Gender is also playing a part in how governments apply their lockdowns, to the frustration of many. The municipal government of Bogotá, Colombia, and the national authorities of Panama and Peru announced measures to enforce social distancing compliance based on their understanding of gender. The measures established different time frames for women and men to leave their homes. These measures were not conceived as a response to gender inequality but as a “practical” means to avoid agglomerations in streets and public spaces in the context of the health emergency.

The measures, however, immediately triggered a wave of discontent. One direct point of criticism came from LGBTQ community, and the case of a trans health worker who was fined in Panama for violating the norm made international headlines.

Other critics of the restrictions say they don’t take into account that women across Latin America are still those primarily responsible for domestic tasks, such as shopping for food and medicine. In Peru, the measure caused an unexpected overcrowding of supermarkets and pharmacies during the “women’s day out”. The policy was scrapped after a few days.

“The gender-based mobility norm has positive and negative consequences,” said Plashka Meade, the deputy resilience officer for Panama City. “But more importantly, it reveals the historical debts and inequalities in our societies.”

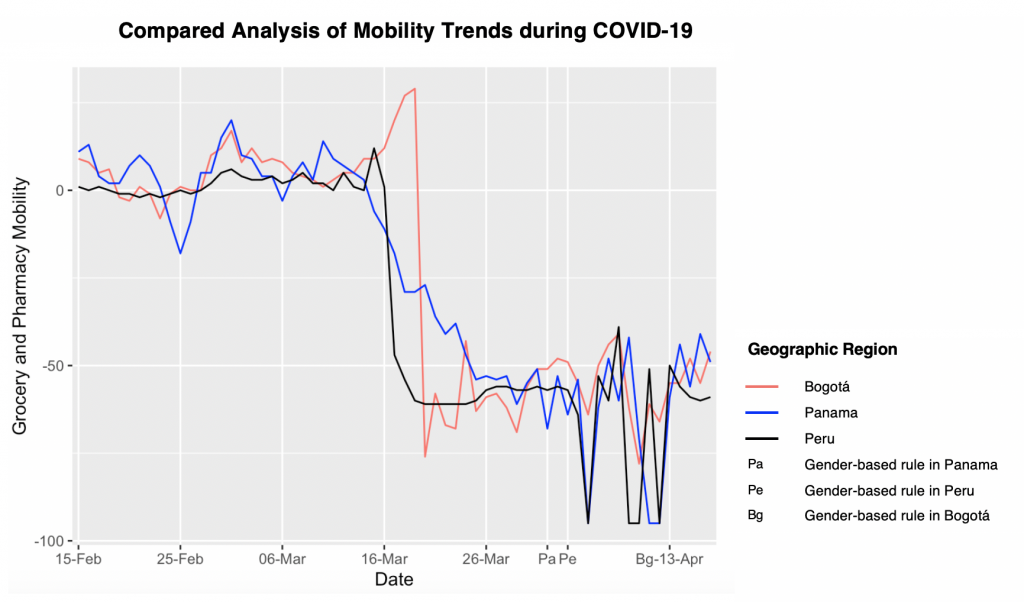

Critics also point to the fact that there is no clear evidence that gender-specific social distancing rules contribute to the primary goal of reinforcing the quarantine. The graphic above compares mobility trends for trips to grocery stores and pharmacies in Peru, Panama and Bogotá, noting when the gender-based confinement rule was implemented. Preliminary data already shows that mobility has not been significantly altered since the gender policies were enacted in each one of the three jurisdictions. Indeed, other factors may impact compliance with confinement policies more, such as the levels of informality (both in terms of economic and housing informality), levels of trust in the current government, and measures taken by specific employers or institutions.

The Case of Bogotá

Bogota’s “pico y género” program, literally “peak and gender” and inspired by the Colombian capital’s “pico y placa” program (“peak and plate”), a policy aimed at reducing traffic congestion and pollution— is underway. Established by Mayor Claudia López on April 13 to organize the quarantine, “pico y género” allows for women to go out of their homes to buy basic goods and food on even-numbered days, while men can only go out on odd ones.

In response to criticism from human rights groups and the LGBTQ community, López – Bogotá’s recently-elected progressive, first female, and out lesbian mayor – said that authorities should respect the gender “people identify with.” Still, Colombia’s strong civil society has put pressure on López to back off from the policy. Other Colombian cities have established similar policies to enforce the lockdown based on identity card numbers, instead of gender. The decision of Bogotá’s local government to stick to this policy remains controversial.

Like the cases of rising domestic violence, gender-based restrictions underscore how structural responses to a crisis can reveal deeper, more perplexing challenges. It is true that most countries in Latin America have established measures to prevent and prosecute gender related violence. However, the region remains as one of the most hostile regions for women. Using gender as an element of division and not of social cohesion unveils the heavy historical weight of gender inequality in the region, reinforcing prejudiced stereotypes, giving a wrong signal as to how men and women should commonly join forces to counter this and other types of crises and reminding us that policies must take into account that real equality requires lasting society challenges.

—

Zapata-Garesché is managing director for Latin America and the Caribbean at the Global Resilient Cities Network and a member of Americas Quarterly’s Editorial Board. Cardoso is a consultant on Resilience Programs and Operations for Latin America and the Caribbean at the Global Resilient Cities Network.