For the first time in United States history, three of the nine justices sitting on the Supreme Court are women. About 33 percent of state and federal court judges in the U.S. are women, slightly higher than the global average of 27 percent.

Why does this matter? Scores of empirical studies have attempted to determine whether the gender of a judge makes a difference to his or her decisions. But regardless of whether it does, equal representation for women in the judiciary strengthens the rule of law and should be a goal across the Americas.

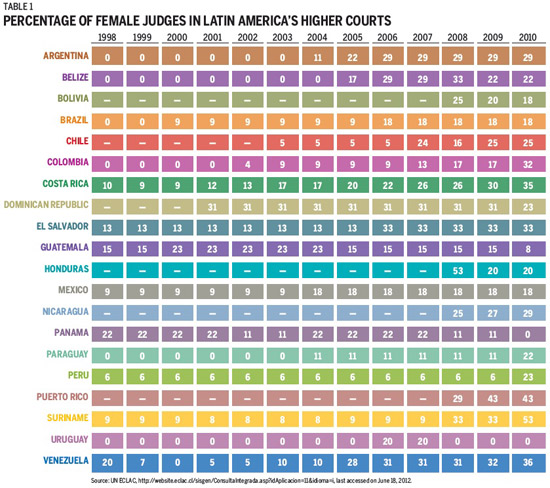

Increasingly, women in the region have overcome stiff challenges to becoming judges. Although the statistics for Latin American countries are slightly lower overall than in the U.S., they signal impressive progress. [See Table 1] For example, in 2010 18 percent of judges in Brazil’s highest court were women, compared to 0 percent in 1998. In Peru, the figure was 23 percent in 2010 versus 6 percent in 1998.

A notable exception to the low representation of women on judiciaries is the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court—the highest court for nine countries, including Antigua and Barbuda, Grenada and Saint Kitts and Nevis. Over 60 percent of judges on this court are women.

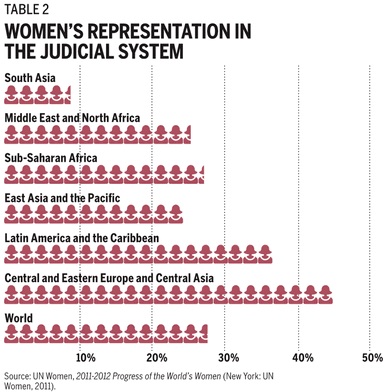

In terms of gender parity, courts in Latin America and the Caribbean rank second in the developing world. [See Table 2] According to the 2011–2012 UN Women report Progress of the World’s Women, Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asian countries have the most women judges in the world—over 40 percent.1

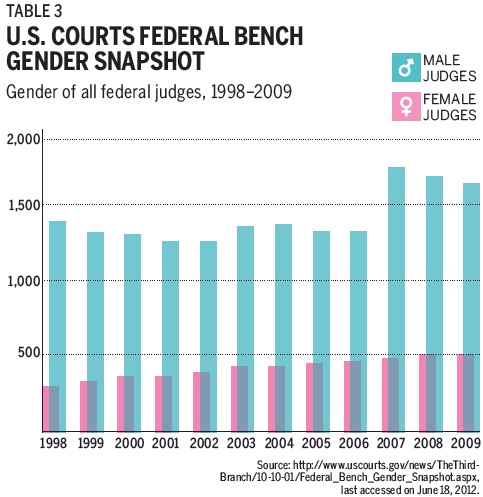

Even in the U.S., progress toward equality on the courts has been slow. While women occupied approximately 20 percent of all federal judge seats in the U.S. a decade ago, they fill only about 30 percent of such seats today. [See Table 3] Although the Canadian Supreme Court, in which four of nine judges are women, is touted as the world’s first gender-balanced national high court, women comprise about only 32 percent of all judges in Canada’s lower courts.

More troubling still: in some countries the share of women judges has actually decreased over time. Take Guatemala, where women constituted 15 percent of judges on the highest court in 2009, but only 8 percent in 2010. In Panama, women constituted 11 percent of judges (one of nine) on the highest court in 2009, but were entirely absent from the court in 2010. The precise reason for this is unclear, but women were not appointed to fill seats vacated by women judges. In Panama, for example, the Supreme Court’s nine justices each serve a term of only 10 years, so there is fairly frequent turnover and an increased possibility of losing women on the bench.

Getting Into the Club

Across the globe, women judges report that an “old boys’ club” mentality surrounding judicial appointments poses a crucial barrier to entry in the legal profession, particularly in the higher courts.

In the vast majority of cases, judges are appointed by the executive or legislature, sometimes upon the recommendation of commissions—which puts a premium on political connections. Women are typically less connected to these appointment and selection mechanisms than are their male colleagues. In some countries, depending on the level of the court, judges are selected by merit, on the basis of performance on exams. In courts where exams are used to select judges, women tend to be represented in higher numbers. In one such country, France, over 50 percent of the judges are women.

A U.S. survey conducted in the early 1990s by the Task Force on Gender Bias for the Federal Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit found that men and women judges and lawyers in the U.S. have different perceptions about gender bias.2 Female judges and lawyers believed that women are excluded from formal and informal networks that influence judicial selection, while male judges and lawyers generally believed that the gender composition of the judiciary was a consequence of merit-based decision-making. Similarly, a 2006 survey of 239 judges in Texas found that 27 percent of women judges believed women had a more difficult time than men in becoming a judge, while only 17 percent of the male judge respondents thought that was the case.3

These findings have not been limited to the United States…