This article is adapted from AQ’s latest issue on Latin America’s anti-corruption movement.

Alberto Gavazzi, Diageo’s President for Latin America & Caribbean, Global Travel and Global Sales, sat down with AQ editor-in-chief Brian Winter to discuss the scope of the problem — and potential solutions.

Brian Winter: What do we mean when we talk about illicit trade in the alcoholic beverage industry?

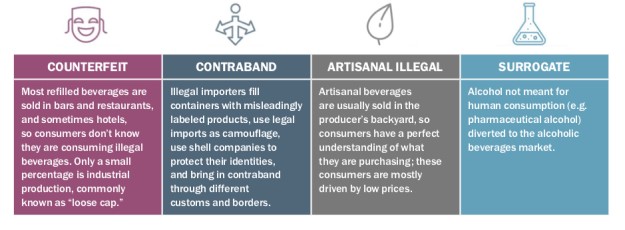

Alberto Gavazzi: Illicit trade is a significant issue. In Latin America, about 20% of the alcohol consumed is illicit. This includes illegally imported alcohol, counterfeit brands, and non-licensed brands. Illicit is not equal to counterfeit. What these three things have in common is that illicit vendors do not pay taxes. In Brazil and Mexico, Latin America’s largest markets, illicit trade in alcohol is a particular problem. In Brazil, about 28 percent of alcohol is sold illicitly, while that figure grows to 36 percent in Mexico, according to Euromonitor International.

BW: Why is the illicit alcohol trade a problem?

AG: A major problem is the consumption of product that is not good quality. Companies that trade legally invest in their production, quality control, facilities and people. Although we participate in an over-regulated industry, in some cases production and quality are not well regulated and it is important that alcohol is clearly traceable.

BW: What can be done to address this problem?

AG: As responsible producers of alcoholic beverages, we have to look for ways to work with governments to reduce the impact of illicit sales, as it is clearly an issue today and could become an even bigger health issue if not managed properly.

Taxes on alcohol in Latin America are amongst the highest in the world — particularly for spirits — and illicit producers can undercut legitimate products. That is why it is important that governments assess the impact of lowering these taxes. We have done studies with Euromonitor International that show potential tax revenue gains for governments if they address this problem. For example, in Mexico, if that 36% of illicit alcohol volume were to be replaced by companies or brands that pay taxes, annual government revenues could increase by around $500 million.

BW: What are the incentives for illicit alcohol traders?

AG: When the potential profit margin is high and the risk is low, it creates the perfect situation for illicit traders, so there are two ways to address this. First, you can increase the risk. In Latin America, those caught in illicit activity face light penalties. You may go to prison for a couple of months but then you are on the street again doing the same thing. Secondly, you can decrease the profit margin by lowering taxes on alcohol. Addressing this would benefit the consumer, first and foremost, but also government and industry. It’s a win-win. The tax rate on spirits in Mexico is currently 77.5 percent, and in Brazil it is 80 percent. So the correlation between high taxes and volume of illicit alcohol sales is very high.

BW: How receptive have governments around Latin America been to making these changes?

AG: Intellectually, a lot. But put into perspective with everything else that needs to be done, it is often a lower priority. But if we tackle this from a broader perspective, looking not just at illegality, but also viewing it as a potential health issue and revenue source, it could be more attractive for legislators to address. The potential social and financial impact is huge.

Colombia has several places referred to as open malls. At these malls, basically all the product is illicit in one way, shape or form. You find everything from toys, clothes, consumer products, sneakers or even medicines. And although everybody is aware of this, people still shop there. Why do we tolerate that? Why do we think it’s okay for those products to be sold? If industries go to governments individually, it’s just a drop in the ocean. If we go together, that is, all industries affected, then we can take action. It’s time to show the negative impact that illicit trade has socially and the positive impact it can have if addressed.

There is a lot of goodwill from governments in terms of working with the industry to address illicit trade. In Mexico and Brazil, we have signed MOUs with the federal revenue agency; in Peru and Costa Rica we have conducted summits; and in Colombia the government is seeking better manufacturing controls. But better actions require better policy, and as long as the tax rates are high, there is an incentive for consumers to buy illicit alcohol.

BW: Which countries do you think face the biggest challenges in Latin America?

AG: Brazil, Mexico and Colombia, because these are the biggest markets. Other markets deal with illicit alcohol trade in a much better way. Chile, for instance, is more aggressive in its border control policies and more flexible in tax policy. Given the resulting higher risk and lower profit margin, the incentive to produce and sell alcohol illicitly is low. We need to take away the incentive in other countries too.

BW: Across Latin America, corruption and lack of rule of law are huge problems. This kind of illicit activity is intimately connected to these issues. Is that an effective way to approach the problem — not only with government, but the general public — in terms of explaining how corrosive it is?

AG: Absolutely. Illicit trade is one of the negative consequences of corruption. If you allow it to happen, it can further corrupt societies. If it weren’t attractive, illicit trade would naturally go away. Corruption is a complex problem and it should be addressed holistically. We could stimulate government action to significantly combat corruption if we conduct monitored studies that can measure changes in policy, improve transparency, reduce implicit incentives such as high taxes, and incorporate the active participation of society.