During their first year in the spotlight, the young federal prosecutors leading the “Operation Car Wash” corruption probe seemed to handle themselves with an eerie, almost cinematic grace. From the case’s obscure roots of money laundering at a gas station, to its eruption into an unprecedented scandal that helped bring down Dilma Rousseff’s presidency, the investigators let their casework speak mostly for itself. Their relative seclusion in the mid-sized city of Curitiba only added to their mystique – it was like watching a dozen thirty-somethings from Cincinnati calmly take down half the establishment of Washington and New York, one airtight indictment at a time. When Folha de S.Paulo plastered a group photo of the prosecutors across its front page with the headline “The Untouchables” in April 2015, it was the first time most Brazilians had seen the men (yes, they were all men) – and the description seemed to fit.

But we tend to forget that not even Eliot Ness was perfect – his career ended in alcoholism, a failed mayoral run and his expulsion from the legal profession altogether. Nothing so grave has happened to the Brazilian prosecutors; but in retrospect, it’s a miracle their charmed run lasted as long as it did. The intense pressures of investigating and jailing dozens of Brazil’s most powerful figures, plus their near-deification by local and international media (including this magazine), were bound to eventually result in hubris and mistakes. The first glimpses of their mortality started to appear earlier this year, as Rousseff’s impeachment gained pace, and erupted into full view in recent weeks with a disastrous public presentation of their case against former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, and the heavy-handed arrest of a former finance minister at a hospital just as his wife was being sedated for cancer surgery.

These controversies have resuscitated a series of basic, but difficult-to-answer, questions about the Car Wash probe and its consequences: How exactly will the case end? When? What percentage of Brazil’s political and business elite will end up behind bars? Will the case result in a substantial long-term improvement in Brazilian justice and institutions, as its supporters hope? Or will it fizzle out like the “Clean Hands” investigation in Italy of the 1990s, which resulted in more than 1,000 arrests but little decline in systemic corruption over time?

Spoiler alert: There are no definitive answers to these questions, here or anywhere else. The sheer number of institutions and individuals involved makes a precise forecast impossible. But there is, in fact, a lot we do know. And in my mind, any analysis of where Car Wash is headed must start by addressing the main criticism of the probe itself: that it has become politicized. That the prosecutors and the man overseeing their work, federal Judge Sérgio Moro, have gone well beyond normal judicial tactics of methodically following clues and prosecuting the guilty. That they have employed political thinking and tactics in their casework, and the methods they use to influence the media and the Brazilian public at large.

To which I would reply: Hell yes, Car Wash has become politicized. But out of necessity, rather than design. Indeed, I’d argue that the politicization of the case is exactly what has allowed it to progress this far without being shut down by its enemies. Perversely, it is also the thing that will start to bring the investigation to an end, probably within the next few months.

—

To understand why, it’s important to remember just how much Car Wash has accomplished since early 2014, when it started to become part of the world’s vocabulary. Many of us have become desensitized to the case’s scale since then, but terms like “massive” and “historic” don’t quite do it justice. The investigation began with money laundering at a network of gas stations and exploded when a serial criminal named Alberto Youssef cut a deal with the prosecutors in Curitiba (the capital of his home state) to tell all. Through skillful use of wiretaps, plea bargains and old-fashioned detective work, prosecutors and the Federal Police soon uncovered much more than they bargained for: An entire scheme – the scheme, you could say – by which Rousseff’s Workers’ Party and its allies, including the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party of new President Michel Temer, sought to maintain themselves in power. The core of the con was to overcharge on contracts at Petrobras, the state-run oil company, and use the proceeds to fund campaigns and buy political support. To date, prosecutors have jailed the Workers’ Party treasurer, a senator, some of Brazil’s most powerful executives, and others. In all, they’ve brought criminal accusations against 239 people, sought information from 30 countries, levied about $10 billion in fines and dished out 1,148 years of criminal sentences.

It’s funny, though, because having just written all that, it still seems insufficient. Indeed, the best way to think about Car Wash is that the prosecutors busted the entire Brazilian political system – or at least, the majority of parties that allegedly relied on illicit funds to fill their coffers and personally enrich their leaders and allies. A large chunk of the business world was also implicated – Petrobras alone had annual revenues equal to 8 percent of Brazil’s GDP. Odebrecht SA, the largest of the Petrobras contractors implicated in the scandal, once generated more annual revenues ($41 billion) than the entire economy of Panama. The constellation of implicated entities also includes several government ministries, a large percentage of Congress, Brazil’s second-largest public bank, and so on.

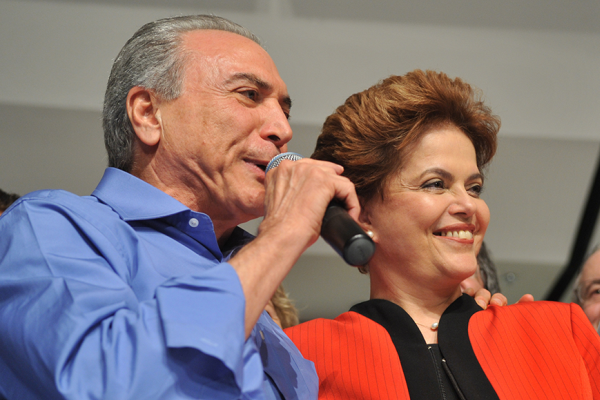

Rousseff and Temer in better days

All of this is to say that, by late 2014, the prosecutors found themselves locked in an existential battle royale with Brazil’s executive branch, most of its legislative branch, and a huge swathe of the business elite as well. With all the lawyers, money, power and political pressure that implies. And make no mistake – the empire did try to strike back. From virtually day one, various interest groups worked furiously to try to move the case out of Curitiba to a friendlier, more politically malleable court; to curtail the use of plea bargains; to reduce the investigative power of the Federal Police; or to have the case thrown out altogether.

So how did the tiny team in Curitiba prevail? By appealing directly to the Brazilian public, and winning the population over to their “side.”

Some of this happened naturally: Brazilians loved watching corrupt politicians and tycoons being led away in handcuffs. This was an especially poignant sight in one of the world’s most unequal countries, where a tiny elite was accustomed to literally getting away with murder. But the Car Wash team believed their only true defense was to make the investigation so popular that politicians wouldn’t dare touch it, for fear of triggering street protests or certain defeat at the ballot box. The prosecutors also bet – correctly, I think – that a robotic, faceless, by-the-book recitation of charges and sentences was not going to accomplish that alone. To build a sufficiently high firewall, they’d have to play the game of public relations – which meant talking to journalists, speaking at conferences and setting up a user-friendly website about the case – with the ultimate goal of convincing Brazilians that the Car Wash probe, if allowed to do its job without interference, would lead to a less corrupt, more fair Brazil.

For this task and many others, the team was blessed with a once-in-a-generation talent: Sérgio Moro, a 44-year-old federal judge. In the Brazilian system, judges don’t collaborate directly with prosecutors, but rule on whether and when to accept the charges they file – and then decide if the defendant is guilty. Moro’s modus operandi is to be extremely conservative at the front end of cases, forcing prosecutors to assemble an impeccable case – but then, once the decision is made, to go after defendants with the full force of the law. As a result, his success rate is not quite 100 percent, but it’s close. One higher court after another has upheld Moro’s rulings as well as his use of controversial tactics, namely the pre-trial detention of suspects. Just last week, a court voted 13 to 1 to reject a motion that would have temporarily removed Moro from the Car Wash case and investigated him for supposed procedural violations.

That record, when paired with Moro’s personal manner – soft-spoken, cautious, humble – has made him an extraordinary spokesman for Car Wash and its larger mission of strengthening Brazilian justice. I’ve seen Moro up close several times at public events and private forums, and people ask me what he’s really like. I reply: “You know, he really doesn’t have that much to say.” People laugh, but I explain that I mean this as the highest possible compliment. Moro seems interested solely in the equal application of the law, rather than any kind of partisan agenda, which is heroic but also, after you’ve listened to the man talk for two hours, kind of repetitive. I know Moro’s critics, who say he is leading a witch hunt against the Workers’ Party, will roll their eyes and call me naive. Fair enough. But most Brazilians have bought what he’s selling: Moro is the only public figure in Brazil with an approval rating consistently above 50 percent; he is greeted in public with rapturous applause; his face adorns murals, Carnival floats and bumper stickers. No government – neither Rousseff’s nor Temer’s – has so far dared to mess with him or the investigation in any meaningful, sustained way.

Thanks to this overwhelming public approval, Moro and the prosecutors have gotten this far. But their approach also has a major drawback: Once you start to play the political game, once you step on that field, a kind of countdown clock starts to go tick tick tick. Because by moving beyond pure jurisprudence, and including public relations in your focus, you become vulnerable to the inevitable ebbs and flows of public opinion. Because unfortunately, not everybody on the team will play the game as well as Moro. As the case’s endgame draws closer, the pressure will get even greater. Over time, you will make mistakes. Sometimes, really big ones.

—

On September 14, the Curitiba prosecutors convened a press conference where, after months of anticipation, they would finally present their case against former President Lula, who governed Brazil during the years the Petrobras scheme took root. I tuned in late, with the presentation already underway. But within just a few seconds, it was obvious that things had gone horribly wrong.

The prosecutor giving the presentation, Deltan Dallagnol, is a 36-year-old Harvard Law graduate who cites Gandhi as his inspiration and is, by all accounts, a brilliant legal mind. But unlike Moro, who has never given an on-record interview and steered well clear of social media, Dallagnol is a regular presence in the media as well as on Facebook and Twitter, where his profile describes him as a “follower of Jesus” and a “passionate father and husband.” He posts constantly about the need to pass new federal anti-corruption legislation, and has traveled to Brasília to press Congress for its passage. Which is to say that Dallagnol has been skating for months on the edge of what is acceptable in the blurring of politics and the law.

On that Wednesday, before a live television audience of millions, Dallagnol wiped out. Instead of focusing on the relatively narrow (but still significant) charges that Lula received more than $1 million in benefits from a construction company, Dallagnol went much further. He called Lula the “master” and “maximum commander” of the entire Petrobras corruption scheme, but did not present formal charges to that effect or provide sufficient evidence to support the claim. Much ridicule has been directed at the prosecutors’ amateurish Power Point presentation, which put “LULA” in the center of a circle with a bunch of arrows pointing at it. But what immediately caught my attention was Dallagnol’s tone – tense, self-righteous, political. Which, at a purely human level, I get: Lula is their Moby Dick. But the stakes at this stage are too high, and the audience too unforgiving, to make such mistakes.

Condemnation came right away, and not just from the usual suspects. “It’s inadmissible,” seethed Reinaldo Azevedo, one of Brazil’s most rabidly anti-Lula columnists, “that an accusation of such gravity would be made public merely as support for another accusation that is stupidly smaller and less important … Where are the charges?” The head of the Brazilian Order of Lawyers called the presentation a “spectacle.” Folha de S.Paulo newspaper, also no friend of the Workers’ Party, lamented that the prosecutors had “failed to present robust evidence … and tried to fill the gap with rhetoric.” Lula himself quickly staged a rally where he declared, sobbing: “Prove any corruption by me and I’ll walk to the police station myself.”

Sensing opportunity, the foes of Car Wash acted with remarkable speed. Five days after the ill-fated press conference, with President Temer on an official trip to New York, a group of legislators daringly tried to pass a bill that would have granted retroactive legal immunity to politicians and companies that engaged in illegal campaign finance. The bill was shelved before it came to a vote; even for a Congress where 60 percent of legislators are under investigation for some kind of crime, this was too bold – testimony again to the perceived political cost of messing with Moro and company. The next morning, nobody would even admit whose idea the maneuver was. But the fact they tried so soon after the prosecutors’ misstep was not a coincidence; and the margin of failure was not large. Forebodingly, one of Temer’s top aides even said he was in favor of the bill.

Dallagnol presents the case against Lula, September 14, 2016

The lasting effect of Dallagnol’s mistake, and the incident days later with the former finance minister and his ailing wife, is unclear. Such errors may be forgotten if eventual plea bargain testimony from Odebrecht’s former CEO is as dramatic as most expect, or if Lula ends up in jail. But it’s hard to escape the sensation that the trend line for Car Wash is pointing down. The case has been going on for more than two and half years. Some are eager to minimize its disruptive effect on Brazil’s economy, trapped in its worst recession ever. The fact that Rousseff was impeached in August means that some Brazilians are ready to move on. The center simply cannot hold forever.

Moro, as the case’s shepherd, has always been conscious of this. A decade ago, he studied Italy’s “Clean Hands” investigation – and he has highlighted how the case sprawled too far and for too long, and eventually fizzled as a result. “As long as it can count on the support of public opinion, (an investigation) can move forward and produce good results,” Moro once wrote of the Italian probe. “If that doesn’t happen, it will hardly succeed.” At a conference in Washington in July, Moro said: “I hope to conclude my role in Car Wash by the end of the year.’” Once you allow for the fact that (pardon me for saying this) hardly anything in Brazil ever concludes on time, it’s reasonable to expect that the investigative phase of Car Wash will largely wrap up by the first quarter of 2017. The criminal trials themselves could, of course, go on for years.

What does this mean in practice? Here again, the uniqueness of the case comes into play – remember, the prosecutors busted the entire political system. They have a trove of bank statements, plea bargains and wiretaps that point to corruption well beyond Petrobras and into similarly massive entities like the BNDES, Brazil’s state development bank. In a world of unlimited resources and no political factors, prosecutors could probably spend the next 20 years investigating just the leads they already have. One source close to the Curitiba team told me they think they “probably could put close to 100 percent of Congress in jail.” But in the real world, they know this is more than the system would bear. So they will focus instead on jailing the ringleaders – the people at the top of the Petrobras scheme’s organizational chart. Some of the mid-level operators, and peripheral corruption schemes, will inevitably go unpunished – or be taken up by other, less accomplished courts.

Is that fair? No, it’s not. But it’s not even a political tactic – it’s a classic investigative one. It may also be the strategy that gives Car Wash the best odds of leaving a strong, intact legacy.

—

Throughout the misery of the past year, many Brazilians have clung to one hope: that the Car Wash probe would lead to a quantum leap in the quality of their institutions. Even as unemployment soared beyond 11 percent and one weak, unpopular government gave way to another, voters have consistently identified corruption as their country’s number-one problem in polls. Foreign investors have also cheered the probe, apart from a minority who worship the false god they call “stability.” A less corrupt Brazil will be a better place to do business, and a better place to call home. One popular T-shirt seen at demonstrations in support of Car Wash reads: “I don’t want to live in another country. I want to live in another Brazil.”

That said, success is not guaranteed – not yet. Some of the probe’s legacy will depend on who goes to jail, and whether the sentences stick. Moro accepted the relatively narrow corruption charges that Dallagnol and his team filed against Lula this month – but Lula is a defendant unlike any other, with a tarnished but still powerful brand among poorer voters and many powerful allies at home and abroad. Meanwhile, it is still possible, if unlikely, that the investigation could unravel on a technicality or some other unforeseen event. Many commentators have darkly noted that “Clean Hands” left a political vacuum in Italy that culminated in Silvio Berlusconi as prime minister. If a populist demagogue succeeds Temer as president in 2018, history will look at Car Wash in a different way.

But I believe that, even if Car Wash doesn’t get a Hollywood ending, the case has still forever changed the culture of impunity in Brazil – and perhaps beyond. The sight of once-powerful people like Marcelo Odebrecht, Antonio Palocci and Delcídio do Amaral being led away in handcuffs has altered the cost-benefit analysis of anyone who considers paying or receiving a bribe. Corruption never totally disappears; but it can be greatly reduced in the course of a generation. The most encouraging development is the proliferation of other probes throughout Brazil that cite Car Wash as their inspiration. The case also has its admirers in places like Mexico, Guatemala, Argentina and Peru. That this all started in Curitiba is remarkable – I’ve seen the prosecutors’ cramped, unglamorous offices, the meager resources at their disposal, and the tiny shrine of posters and Brazilian flags erected by their admirers just across the street. What they’ve already accomplished is truly extraordinary.

At the end of the 1987 film version of “The Untouchables,” when Al Capone is being led away from the courtroom by police, Eliot Ness confronts him, jabs a finger and says, repeatedly and with controlled emotion: “Never stop fighting until the fighting is done.” That was just a movie, of course. Car Wash is real – and the fighting isn’t done quite yet.