Brazil | Colombia | Costa Rica | Mexico | Paraguay | Venezuela | Cuba

See above for a breakdown of the region’s other 2018 transitions, or click here for the full list from our print edition.

Election date: February 4

Format: Two rounds. If no candidate receives 40 percent of votes in the first round, the two leading candidates will proceed to a run-off on April 1.

Carlos Alvarado, 37, former minister

Carlos Alvarado, 37, former minister

Citizens’ Action Party

“The fight is against neoliberalism and corruption.”

How he got here: A political scientist, journalist and novelist, Alvarado served as communications director for Guillermo Solís’ successful presidential campaign four years ago. That connection helped him land the role of human development minister and later labor minister, where he proved skillful at negotiating with the private sector.

Why he might win: Though a ruling party candidate, he presents himself as a politician of change — a discourse he effectively used in 2014 to help Solís. At 37, the center-left Alvarado emphasizes issues, such as job creation, same-sex marriage and climate change, that matter to the half of the electorate under 40.

Why he might lose: Alvarado will suffer if voters associate him with the ongoing cementazo scandal, an influence-peddling investigation touching members of the president’s inner circle and all three branches of government.

Who supports him: As the closest among the candidates to a Costa Rican Justin Trudeau, Alvarado can expect support from young, urban middle-class sectors. A believer in the role of the state, he’s also best positioned to attract state employees.

What he would do: Maintain Costa Rica’s state-run oil and electricity monopolies, support job creation through public-private alliances, and advocate for same-sex marriage, an issue picking up steam in Costa Rica.

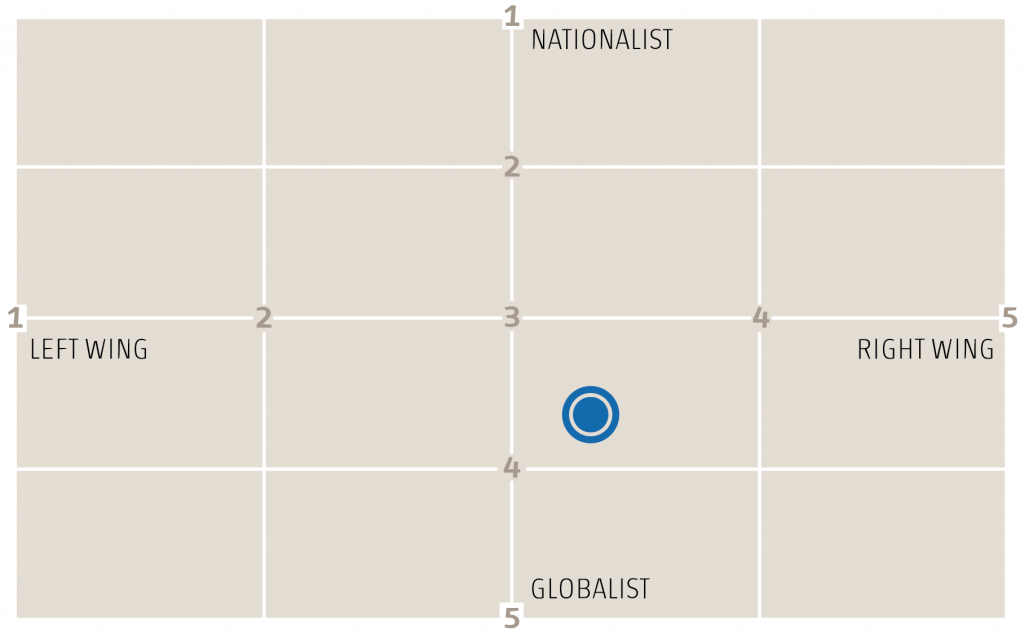

Ideology:

AQ asked a dozen nonpartisan experts on Latin America to help us identify where each candidate stands on two spectrums: left wing versus right wing, and nationalist versus globalist. We’ve published the average response, with a caveat: Platforms evolve, and so do candidates.

AQ asked a dozen nonpartisan experts on Latin America to help us identify where each candidate stands on two spectrums: left wing versus right wing, and nationalist versus globalist. We’ve published the average response, with a caveat: Platforms evolve, and so do candidates.

Antonio Álvarez Desanti, 59, former congressman

Antonio Álvarez Desanti, 59, former congressman

National Liberation Party

“I’ve made decisions when I’ve had to make them, and Costa Ricans know that.”

How he got here: A veteran businessman, Álvarez served as the agriculture and livestock minister from 1987 to 1988 and as interior and police minister from 1987 to 1990 under then-President Óscar Arias. Álvarez has since crafted a reputation as a skilled politician—the type who might spend decades in Congress if Costa Rica allowed consecutive re-election.

Why he might win: Though the National Liberation Party has seen its share of voters cut in half in the past two decades, it’s still the country’s largest party. That support could help him make the runoff, and if a polarizing candidate like Juan Diego Castro makes it there with him, Álvarez might stand a chance.

Why he might lose: Álvarez is an establishment candidate at a moment of anti-system sentiment, and this is reflected in his 38 percent rejection rate — the highest of all the candidates. Some also see his long political career as one marked by opportunism. Quitting his party in 2005 and rejoining in 2007 lost him support within the party. Young voters are also put off by Álvarez’s increasingly conservative views, a result of his party’s recent alliance with evangelicals.

Who supports him: The business class, and poorer, rural voters,

particularly on the coast.

What he would do: Known foremost as a businessman, Álvarez is expected to pursue a liberal, pro-business agenda similar to that of his former boss, Arias. Expect him to push for foreign trade and investment and the opening of Costa Rica’s monopolies

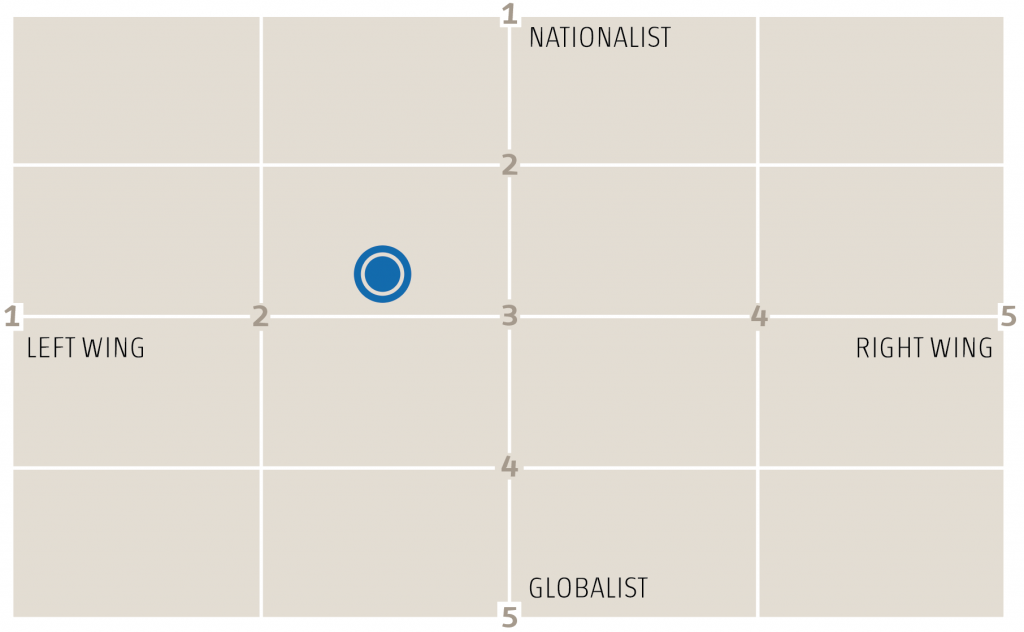

Ideology:

Juan Diego Castro, 62, former minister

Juan Diego Castro, 62, former minister

National Integration Party

“The corruption of the political parties is already showing its fangs and claws to frighten us.”

How he got here: A long-time lawyer, Castro served as security minister from 1994 to 1996 and later as justice minister, during which time he gained a reputation for controversy and resigned before a year had passed. He is best-known as a fixture on Costa Rica’s top TV channel, where he’s become a go-to pundit on crime and security issues. On his Facebook page, Castro regularly taps into the anti-establishment sentiment felt by many of his 275,000 followers.

Why he might win: Though a politician himself, Castro’s anti-system message appeals to voters turned off by a political establishment newly embroiled in scandal.

Why he might lose: Castro’s controversial style — he denies comparisons to Donald Trump — may not sit well with the average voter. He attacks parties, but lacks a strong party base of his own that could be necessary to win.

Who supports him: Less-educated, older and mostly male Costa Ricans, and those worried by corruption and rising insecurity.

What would he do: An aversion to interviews means Castro’s policies are hard to predict. He’s unlikely to stray from his anti-corruption message, and has promised a state anti-corruption agency housed in the public security ministry. Critics fear his authoritarian tendencies and antagonism toward the press could worsen as president.

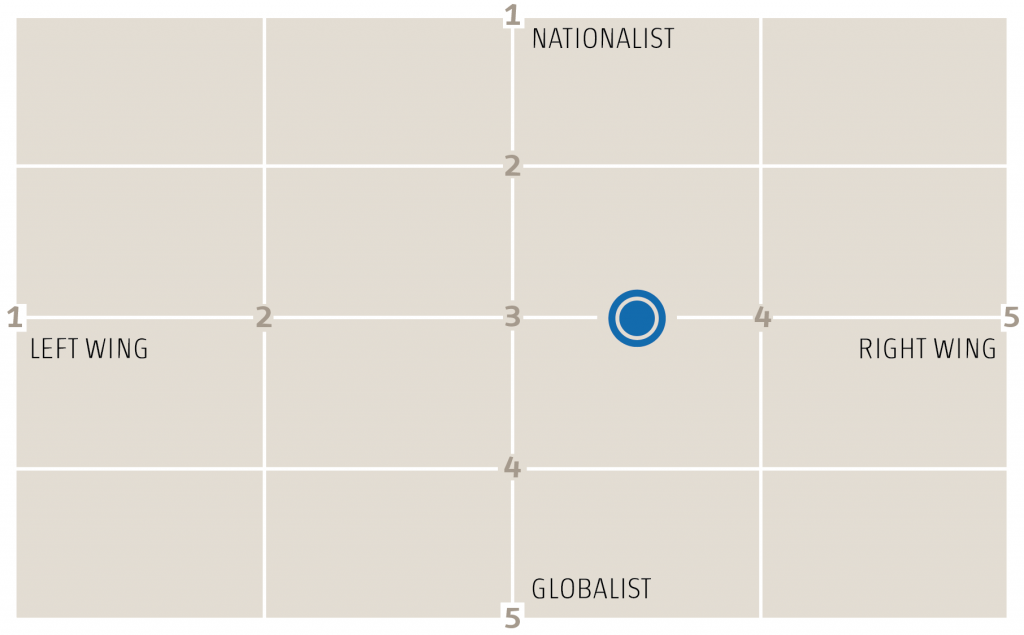

Ideology:

Rodolfo Piza, 59, former supreme court justice

Rodolfo Piza, 59, former supreme court justice

Social Christian Unity Party

“The country needs a change—an urgent change. I’m not interested in the task of searching for someone to blame.”

How he got here: A constitutional lawyer, this son of one of Costa Rica’s most famed jurists is well-respected by figures across parties. A former chief executive of the social security fund, Piza’s second bid for the presidency is expected to be more successful than his first, when he finished fifth.

Why he might win: The pragmatic Piza appeals to Costa Ricans who, on the whole, prefer centrists and might be alienated by more extreme candidates. With more polarizing candidates like Castro and Álvarez, Piza may win just for being the moderate alternative, much as Guillermo Solís did in 2014.

Why he might lose: Piza ran in 2014 and only scraped up 6 percent of votes. His straightforward personality could be taken for a lack of charisma.

Who supports him: Voters in poor provinces, and moderate voters attracted to his conciliatory approach to politics.

What he would do: Though fiscally and socially conservative, Piza’s specific economic policies are difficult to pin down. He’s campaigning hard on a promise to overhaul Costa Rica’s deteriorating infrastructure, promising to build a $900 million subway system in San José.

Ideology: