Indigenous people have been migrating to the U.S. from Oaxaca for nearly a century. The first documented large-scale migration began in 1942, when the Bracero Program opened the U.S. border to temporary agricultural workers from Mexico. Although that program ended in 1966, the flow northward continues. But there have been few academic studies exploring how the movement of indigenous peoples across the U.S.-Mexico border has affected the culture and politics of their communities.

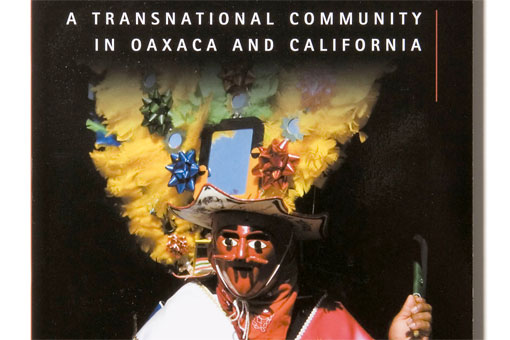

Migration from the Mexican Mixteca: A Transnational Community in Oaxaca and California attempts to fill that gap. It provides a detailed look at the settlement patterns and the social integration of migrants from San Miguel Tlacotepec in Oaxaca who now reside in San Diego County, California. Drawing on interviews and other field work conducted in 2007–2008 by 32 graduate students at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), the book provides useful empirical information and data, as well as an analysis of the link between immigration, transnationalism, international relations, and economics. This is the fourth in a series of studies on Mexican migration conducted by the Center for Comparative Immigration Studies, with oversight from Wayne A. Cornelius, David Fitzgerald and Scott Borger of UCSD and Jorge Hernández-Díaz of the Universidad Autónoma Benito Juárez de Oaxaca.

According to the book, an estimated 30 percent of Tlacotepec’s 3,307 residents have left town, having migrated to more economically developed parts of Mexico or to the United States. The community is therefore an excellent choice for analyzing both the indigenous experience of migration and the transnational forces that connect sending and receiving communities.

Initial chapters cover the economic, social and political push-and-pull forces in the Tlacotepec-San Diego migratory process. But the book’s most important discussion comes in the chapter on the civic, political and cultural participation of indigenous migrants in both their places of origin and destination. Here, researchers often grapple with how the indigenous migrant experience differs from that of the non-indigenous.

UCSD students Elizabeth Perry, Nishma Doshi, Jonathan Hicken, and Julio Ricardo Méndez García attempt to shed light on this question by analyzing the customary rules (of collective decision making and communal leadership) that structure indigenous civic and political participation and how those are affected when migrants return home.

Despite strict rules of eligibility that limit candidates for municipal posts to those who have previously served in public office, the authors discover that many migrants in San Diego continue to play a leadership role at home, even if not officially elected. “Out-migration has compelled Tlacotepenses to modify the system of political, religious and social cargos [positions] in their town,” the researchers conclude. New initiatives lower the requirements to hold office, allow community members to carry out migrants’ leadership duties and limit the expectations that absent townspeople will actively participate in local decision-making bodies. One political by-product of the prolonged absence of fathers, husbands and sons is that more women now participate in town committees.

What remains to be studied is the importance of other factors—besides maintaining political and civic connections at home—on preserving migrants’ ethnic identity. The authors suggest that prolonged disconnection from their roots makes it increasingly difficult for indigenous peoples to remain culturally distinct from other Latino migrants to the United States.

Another insightful chapter focuses on the role of technology in migrant networks. UCSD students Leah Muse-Orlinoff, Maximino Matus Ruiz, Chelsea Ambort, and John E. Cárdenas survey the use of public telephones, private landlines and videoconferences among migrants involved in hometown associations and local leadership committees. Not surprisingly, the authors find a rise in the use of the Internet and other technologies among youth, predicting that services like Skype and instant messaging will gain importance in the transnational community.

Migration has also affected lifestyles within the Tlacotepec community. The chapter written by Clare Appleby, Nancy Moreno and Arielle Smith suggests that stronger border control has affected women’s decisions about when to migrate. Marriage and pregnancy are also generally postponed until settling in San Diego.

On the health front, Whitney L. Duncan, Laurel Korwin, Miguel Pinedo, Eduardo González-Fagoaga, and Durga García find that although the use of traditional and alternative healers is embedded in the cultural practices of some non-migrating Tlacotepec residents, most seek treatment for serious illnesses at a government clinic. In turn, migrants then seek similar care in San Diego. However, California’s undocumented population has limited access to services, which contributes to high rates of non-life threatening illnesses such as depression and anxiety and problems of alcohol and drug abuse.

Overall, the book is an excellent resource for immigration practitioners and researchers. But it would have benefited from a conclusion that better summed up the research and tied together the individual chapters. A consolidated bibliography and an overview of data analysis methods would similarly help academic readers identify new avenues for study. Still, considering the minimal amount of scholarly attention paid to indigenous migration, this book represents a major addition to the literature.