This article is adapted from AQ’s print issue on reducing homicide in Latin America.

Dressed in breeches, a ruffled shirt and a menacing black cape, the actor jabs a finger at the Paraguayan sky. “They say I am the forger of the national character!” — he spreads his arms, imploringly — “but am I to blame for the future evils of my country?”

For nearly 30 years, Jorge Ramos has played the role of Dr. José Gaspar de Francia, first ruler of Paraguay and the country’s most enigmatic and divisive historical figure. As he stalks across the Asunción stage that same night, wide-eyed children in the front row clutch each other tightly.

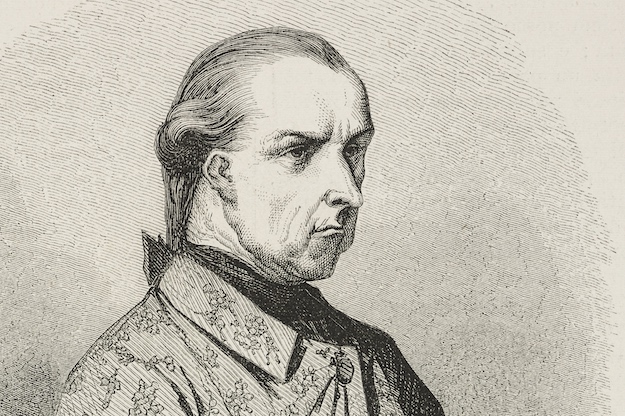

Francia has long inspired such awe and confusion. Contemporary accounts by foreigners dwell on the penetrating gaze and fearsome temper of “El Supremo,” who, upon coming to power in 1811, turned Paraguay into a country unlike any other on the continent, a hermit state in the belly of South America.

Even today, Francia’s reign and the baffling policies he enacted are the subjects of lively historical debate. He has been portrayed as both a hero of national sovereignty and an agent of the Spanish crown; a progenitor of right-wing dictatorships and a popular revolutionary. He is the subject of Paraguay’s most celebrated novel and, in recent years, he has become an icon of nationalists on both the right and left.

In colonial times, Paraguay was the distant last stop on the Spanish trade route. The country, along with much of the continent, declared independence in 1811. But while neighboring countries fought lengthy wars of liberation, the Spanish troops of the Reconquista never bothered with Paraguay.

This set the country on a different course. Elsewhere on the continent, the patriots took their tune from the American independence movement, demanding liberty and equality to win over new recruits.

Paraguay, on the other hand, followed a Roman model of republicanism, with Francia and military man Fulgencio Yegros each holding a consulship. When two curule chairs embossed with the names Caesar and Pompey were commissioned, Francia commandeered the former and wasted little time consolidating power. The poor of the country came to know him as Karai Guazú, “Great Lord” in Guaraní, Paraguay’s indigenous language.

In 1817, as Simon Bolívar was harassing Spanish forces in his native Venezuela and José de San Martín, his Southern Cone counterpart, was marching a ragtag army over the Andes, in Asunción, Francia was settling on his new job title: Supreme and Perpetual Dictator of Paraguay.

He used that power to build a loyal army, nationalize the country’s agricultural and industrial production, and shut its borders, refusing exit passports to any foreigners trapped inside.

With little news emerging from the country, Paraguay became a source of fascination to foreign powers, “an island surrounded by land,” in the words of Paraguayan novelist Augusto Roa Bastos.

The threat

Francia’s tortoise tactics were designed to prevent his country being swallowed up into an Argentine super-state or dragged into the internecine conflict between centralists and federalists along the Rio de la Plata. Less than 30 years after his death, the combined forces of Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay would come close to wiping Paraguay off the map.

He faced an internal threat too, from the traditional Spanish gentry, so he banned marriage among them and turned over their lands to peasants. He also undermined the church, shaving the heads of unruly monks and, in response to his excommunication, stated his intention to make the pope his “personal chaplain.”

He led an ascetic existence, living on a modest salary and refusing to allow streets, statues or coins to be dedicated to him, though today his stern profile appears on Paraguayan banknotes. “Francia, like every smart Paraguayan politician since, spoke Guaraní to appeal to Paraguayan smallholders,” Thomas Whigham, a historian specializing in 19th century Paraguay, told AQ. “He crystallized national identity as ‘being apart from neighboring peoples.’”

For U.S. historian Richard Alan White this represented a “radical social revolution,” and the view of Francia as a tropical proto-communist persists in the 21st century. When an obscure left-wing guerrilla group, the Paraguayan People’s Army (EPP), emerged in northern Paraguay in 2008 their banners featured Francia alongside Marx and Lenin, and their leaders described the group’s ideology as “21st century Francismo.”

Suppressing dissent

It was as an authoritarian, however, that Francia left his most indelible mark. According to the account of a Swiss physician trapped in the country, Francia admired the French revolution for its enthusiastic application of the guillotine.

He was ruthless toward political dissent. Caricaturists were put in chains, and when a Spaniard was overheard speculating on when Francia might expire, he was dragged before El Supremo, who told him, “As to when I shall go, I really cannot tell; but this I know, that you shall go before me.” The man was shot dead and his property confiscated by the state.

His terrified countrymen believed Francia’s periodic crackdowns were the result of madness brought on by the blowing of rare northerly winds, but Julio Cesár Chávez, his biographer, believes the source of his mercurial rage was probably syphilis.

Some terms from the period have endured. In 2014 the EPP released footage of hostages under a banner with the word Tevego, the name of Francia’s brutal penal colony. Francia also established a spy network known as the pyragie (hairy feet), a term that resurfaced under General Alfredo Stroessner, Paraguay’s dictator from 1954 to 1989.

“Stroessner was a stated admirer of Francia and there are many similarities in how they governed, in the isolationism, in the use of military force, even in his micro-management,” Richard Scavone, a historian and Paraguay’s current ambassador to Colombia, told AQ.

Like Stroessner, Francia had minimal tolerance for democratic opposition. In 1820, Francia eliminated his rivals, including his former co-consul, Yegros, after discovering an assassination plot. Marga Yegros, his great-great-great granddaughter, told AQ that she disdains those who describe El Supremo as a benevolent dictator. “Historians and politicians continue to portray Francia as a national hero and an idealist. They cover up his brutality and attribute to him merits he didn’t have. People lived in fear.”

The violence wasn’t unusual, but the climate of repression was, according to Whigham. “Francia wasn’t any more bloody than his contemporaries on the Rio de la Plata. However, he extinguished the quest for a more liberal order.”

But nowadays, many view Francia as a symptom, rather than a cause, of Paraguayan exceptionalism, and consider his repressive methods to have been necessary measures to preserve the country’s precarious independence. Whigham believes Francia shaped himself after the despotic governors sent to Latin America by the Spanish crown in the 16th and 17th centuries rather than the liberators of the day. “Paraguay was always the distant edge of the Spanish empire,” said Scavone, and “Francia deepened this isolation, made it almost complete and reinforced authoritarianism.”

The merits of these policies are still the subject of debate in Paraguay, a country with a fragile democracy where many feel nostalgic for the authoritarian rulers of the past. In a café on Yegros Street the day after his performance, Ramos, the actor, said, “Sometimes people congratulate me for portraying Francia as a crazy dictator, but others tell me that we need a ruler like him these days. It’s amazing what people can take from the same show.”

—

Youkee is a journalist based in Bogotá