Walking through El Chamizal Park, a thirsty sliver of 600 acres of land sandwiched between El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, you would hardly consider it a place worth fighting over. A small slice of territory between two very large countries, it is nearly unusable for agriculture and devoid of natural resources.

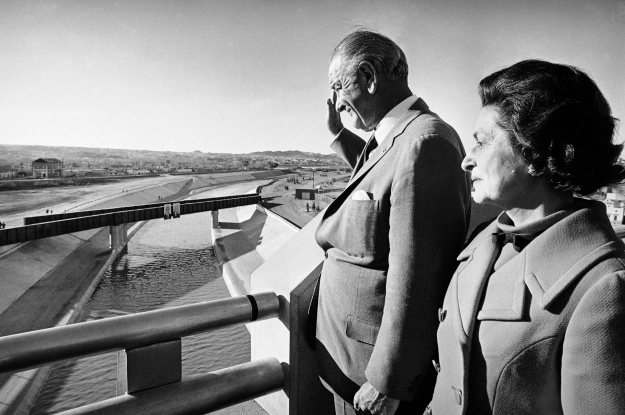

Yet for a full 100 years, El Chamizal was a huge sticking point in relations between Mexico and the United States. The dispute began with the flood of 1864, when the Rio Grande shifted south, leaving El Chamizal as a no-man’s land wedged between the old dry river bed and a new river bank. The fight took surprising twists and turns in ensuing decades — and was even the staging ground for a potential assassination of a U.S. president. The dispute didn’t end until September 25, 1964, when Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Adolfo López Mateos traveled there and finally put the controversy to an end.

In the modern day, most people in both the United States and Mexico have forgotten about El Chamizal. Other issues in the bilateral relationship — such as undocumented migration, illegal drugs and trade deals — have taken center stage. But all these years later, the dispute remains a valuable cautionary tale on how supposedly “small” issues can turn into major irritants in diplomatic ties and linger for decades. In fact, without the resolution of El Chamizal, it is likely that today’s era of cooperation and economic integration between Mexico and the United States would have never been possible.

Several aspects of the dispute remain relevant today.

1. El Chamizal was where Mexico drew the line on U.S. expansionism.

Prior to the flood of 1864, El Chamizal was mostly unpopulated but claimed by Juan Ponce de León, a Mexican landowner. In theory, Mexico should have just accepted the loss of territory after the flood. An 1848 treaty had established the Rio Grande as the border, regardless of natural alterations to its banks. But through the 1870s, most shifts had favored the United States. This continuously irked Mexicans, and it is not hard to understand why.

Mexico had already lost over half of its territory in the Mexican-American War of 1846–1848 and had occasionally lost bits of land after that. El Chamizal was where Mexico finally drew the line.

The first protests were brought to the attention of Secretary of State William Seward in 1864 and 1867, but Washington was too concerned with the aftermath of the Civil War to bother with minor border disputes with Mexico.

By 1889, both governments accepted arbitration of the dispute by a panel presided over by Eugene LaFleur, a Canadian lawyer. The panel recommended dividing the tract of land between the two countries. But the United States ultimately elected not to accept the decision, based on a technicality it said was covered by treaties.

In ensuing years, Mexican citizens who held title to El Chamizal intensely protested private and public uses of the land by U.S. citizens and the city of El Paso, according to historical documents and State Department cables from that era. Mexico also filed diplomatic protests when the city of El Paso attempted to build a sewage and garbage disposal on Chamizal land. By then, it was abundantly clear that Mexico was not going to just let the issue go.

2. It could have been a far more dramatic chapter.

The Chamizal dispute loomed large as Presidents William H. Taft and Porfirio Díaz agreed to meet in Ciudad Juárez–El Paso in 1909. The two presidents intended to cross the border over El Chamizal. No flags were to be flown as a symbol that the area was neutral territory.

All went well until the Texas Rangers detained a man with a handgun along the parade route, not far from the two presidents. It’s impossible to confirm whether this was really an aborted assassination attempt, who the target was, or whether it was related to the Chamizal. But it came at a time of especially high tensions and threats, as Taft had hinted at the possibility of resolving the land dispute, angering many locals. El Paso was also a hotbed of opposition to Diaz, who just two years later would flee to Spain when the Mexican Revolution erupted.

3. It was a significant factor in the Cold War.

While El Chamizal was not the only diplomatic bone of contention between Mexico and the United States, the latter’s disregard for the 1911 arbitration set the tone for a half-century of sour ties. Mexico went on to establish stronger links with the Soviet Union, and became generally hostile to U.S. interests. By the early 1960s, during the Cuban Missile Crisis, Mexico was the only country that voted to maintain Cuban membership in the Organization of American States — greatly annoying the United States. Many of the positions that Mexico took over the decades were explicitly taken to be contrary to American interests.

After losing Cuba to the Soviet Union, the United States realized it needed to redouble its attention to Latin America and try to ensure a modicum of loyalty to U.S. interests. Leaders in Washington knew this involved settling the Chamizal dispute, which was viewed as the last straw of American territorial imperialism not only in Mexico, but also in other countries of Latin America.

Fortunately, the legal basis for the return of El Chamizal was already in place. The 1911 arbitration panel had ruled largely in favor of Mexico. It required only political will to carry it out. For the U.S.,

El Chamizal had no strategic value — even if for the city of El Paso this was an important loss because the land was within its business district. And so, in 1964, on the centenary of the flood, the two countries’ presidents signed the deal along the lines of the 1911 LaFleur panel recommendation — to divide the land between the two countries.

This set the stage for a new phase in the bilateral relationship.

4. Its resolution set the stage for a new era of economic ties.

Starting in the 1930s, Mexico had implemented an economic development model based on import substitution industrialization — a state-led economy with strong central planning, more akin to socialism.

By the early 1960s, however, these policies were showing their limits. New initiatives emerged to create a border-based manufacturing industry, dedicated to taking advantage of much cheaper Mexican labor to produce goods for the American consumer markets. Such a model of manufacturing — the maquiladora industry — could not have occurred without a resolution to the Chamizal dispute, particularly because Ciudad Juárez and Tijuana were envisioned as major maquiladora centers. Business networks on both sides of the border pressed to achieve a resolution to the dispute. As soon as this occurred, the maquiladora model began to really take root.

Indeed, with territorial disputes now in the past and a renewed focus on economic integration, the whole nature of the U.S.-Mexico relationship began to change. Mexico’s turn toward a neoliberal economic agenda in the 1980s and the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994 solidified the shift and led to the era of mostly harmonious collaboration that we know today.

—

Tony Payan is director of the Mexico Center at the Baker Institute. He is also an adjunct associate professor at Rice Univesity and a professor at the Autonomous University of Ciudad Juárez. His research focuses on border studies, particularly the U.S.-Mexico border. He is the author of The Three U.S.-Mexico Border Wars: Drugs, Immigration and Homeland Security.