This article is adapted from Americas Quarterly’s print issue on Venezuela after Maduro

In 1993, the death of cocaine kingpin Pablo Escobar radically shifted the nature of the drug conflict in Colombia. Right-wing paramilitary groups — with the complicity of regional strongmen and their allies in the military — displaced thousands of farmers and the entire population of towns in an effort to clear out Marxist rebels , but also to establish safe corridors to transport their drug shipments to the coast. They left thousands of victims, often in horrific massacres, during this brutal land grab that redrew Colombia’s property map.

While the story of Escobar and the Medellín and Cali cartels has been glamorized in narconovelas and Netflix series, the history of Colombia’s paramilitary armies and the havoc they wreaked has been largely underreported outside of the country. It is a vast and complex saga, with no one epic villain of Escobar-like proportions around which to spin the narrative.

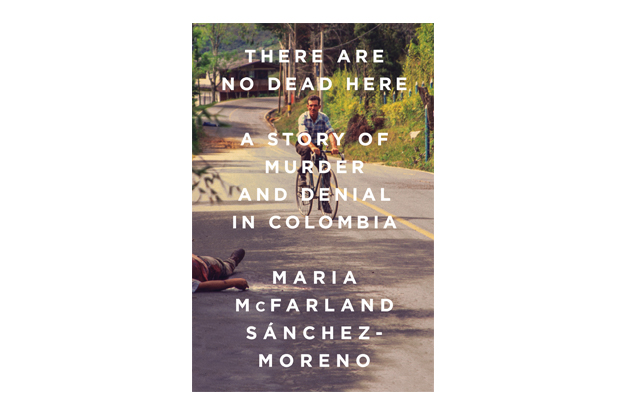

But just as there were villains aplenty, Colombia has its share of heroes who grasped the scale of the criminal conspiracy underfoot and worked tirelessly to ring the alarm and shine a light on those responsible. In There Are No Dead Here: A Story of Murder and Denial in Colombia, Maria McFarland Sánchez-Moreno tells the story of three of these people — a human rights activist, a prosecutor and a journalist — who, at great personal risk, investigated the activities of Colombia’s paramilitary groups and their ties to the political and military establishment.

McFarland begins her account with Jesús María Valle, a lawyer and human rights activist who in 1997 documented the razing of the central Antioquia village of El Aro and the massacre of 17 of its inhabitants by paramilitaries. This was a pattern of terror that Valle was painfully familiar with; in the 1950s, armed groups forcefully evicted his family from their home. Valle’s research into the killings in remote towns of rural Colombia, which the authorities often chose to ignore, earned him dangerous enemies and in 1998 he was tragically gunned down in his downtown Medellín office.

Iván Velásquez, a friend of Valle who began his career as a prosecutor in Antioquia, took up his cause. He won national renown starting in 2007 when he led an investigation that linked several prominent legislators and local officials to paramilitary groups. Velásquez was aided in part by the reporting of McFarland’s final protagonist.

Ricardo Calderón is a policeman’s son who grew up attending the funerals of his father’s colleagues, many of whom had been murdered by Escobar’s henchmen. As a journalist at Semana, Calderón revealed that the national intelligence agency had carried out illegal wiretapping and surveillance on Supreme Court justices to protect the government and silence its critics. Calderón has continued conducting sensitive investigations and in 2013 escaped an assassination attempt.

More than a tribute to these brave men, McFarland’s book is an attempt to ensure that Colombian prosecutors continue to investigate the paramilitaries and bring to justice those who enabled and protected them. As the former senior Americas researcher at Human Rights Watch, where she covered Colombia from 2004 to 2009 — McFarland is now executive director of the Drug Policy Alliance — she is well-credentialed to narrate this account. A Peruvian native who knows the Andean region well, McFarland is both insightful and compassionate. She noted she was often bewildered in Colombia — as many Colombians themselves are — by routine demonstrations of extraordinary courage, honesty and nobility that contrasted with the staggering “capacity for cruelty, ruthlessness and deception of some of the people I met.”

Though the book has not yet been translated into Spanish, it has already caused waves in Colombia. It is, one hopes, a work in progress rather than a mere historical account.

The larger point of McFarland’s book is best explained by its title, a reference to a line in Gabriel García Márquez’s most famous novel, One Hundred Years of Solitude, alluding to the country’s long history of impunity, where even witnesses of a murder will deny that it ever took place. Large portions of the Colombian population may be complicit in this behavior for an all-too-human reason: that the truth behind the country’s seemingly inexhaustible aptitude for violence is simply too horrible to face.