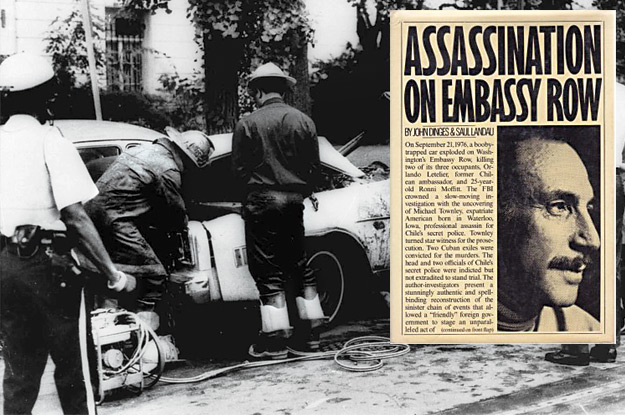

On the misty morning of September 21, 1976, a dust-blue Chevrolet Malibu made its way down Embassy Row in Washington, D.C. At the wheel was Orlando Letelier, who had been ambassador to the United States and minister of foreign relations, interior, and defense under Chile’s Marxist president, Salvador Allende. Following the 1973 coup by Augusto Pinochet, Letelier worked at the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS), a think-tank based in Dupont Circle. He was accompanied by his IPS colleague Ronni Moffitt, 25, and her husband, Michael, who rode in the back seat.

As the Malibu rounded Sheridan Circle, Michael heard a hissing sound. A second later, a bomb underneath Letelier’s seat sent the vehicle flying into the air and crashing down against a parked Volkswagen. Letelier’s legs were blown almost completely off and his torso spun around. He died within minutes. Ronni Moffitt stumbled out of the wreck, but a piece of shrapnel had severed her carotid artery and she drowned in her own blood. Michael Moffitt escaped with minor wounds, cursing the “fascists” who had done this to them.

The Letelier/Moffitt assassination remains to this day the only instance of state-sponsored international terrorism in the U.S. capital. Yet as the 40th anniversary of the attack approaches, its broader meaning in the arc of Latin American history is only now becoming clearer. The Caso Letelier, as it is widely known, was a critical chapter in a regionwide quest for justice for Cold War-era human rights abuses that still continues today. It would also prove to be an astounding display of bravery and persistence by the families of the survivors, as well as a generation of democrats, diplomats and prosecutors.

A Cuban Connection

The search for the killers began immediately after the bombing. The IPS, Moffitt, and Letelier’s widow, Isabel, accused Pinochet’s secret police, the National Intelligence Directorate (DINA), of killing Letelier to stop his peaceful undermining of Pinochet’s government — and to send a message that no one was safe from the long arm of Chilean retribution. Meanwhile, the Pinochet administration and the Central Intelligence Agency attempted to throw investigators off the scent by suggesting that other leftists had done the deed to cast suspicion onto Pinochet.

To their credit, investigators in the FBI and the Justice Department ignored the politics. Instead, they focused on rumors that right-wing Cuban Americans, disenchanted with Washington’s recent steps to normalize relations with Cuba, had killed Letelier to burnish their anti-communist credentials.

In 1978, the U.S. government did indeed prosecute nine coconspirators. Five Cuban Americans were indicted, including four for murder and conspiring to commit murder and a fifth for failing to report the crime. Also indicted was an American expatriate living in Chile named Michael Townley, who made the bomb and planted it under Letelier’s seat, Townley plea-bargained a short sentence in exchange for his confession. Townley said DINA’s director, Manuel “Mamo” Contreras, had ordered the hit through his chief of operations, Pedro Espinoza, and that a DINA operative, Armando Fernández, had helped him surveil Letelier. Townley ended up in witness protection, and some of the Cubans went to prison.

The arrests opened up an even more delicate phase of the quest for justice, as the U.S. government pressured Chile to extradite Contreras, Espinoza and Fernández.

Contreras was an archetypal Cold War psychopath. He harbored a murderous paranoia about “subversives” and was responsible for the murder or “disappearance” of about a third of the roughly 3,000 people killed by the Pinochet regime. Because Contreras hinted he had dirt on many higher-ups in the Pinochet government and had hidden away all DINA documents related to Letelier, the Chilean military and the courts protected him from extradition and, throughout the 1980s, from prosecution.

The obstacles to justice were legion. FBI officials and U.S. judges received death threats. Santiago sandbagged a civil suit to recover monetary damages. The U.S. Congress slapped sanctions on Chile, yet the Pinochet government did not yield. Through it all, Isabel Letelier and her four sons, Michael Moffitt, and Ronni’s parents pursued their cases while struggling against ostracism, depression, alcoholism, seizures, and the need to make a living. “My life was shattered and has never been made whole again,” Isabel testified 15 years after the murder.

Diplomats Were Key

From the Gerald Ford through the Bill Clinton administrations, U.S. diplomats helped the Letelier and Moffitt families keep up the pressure inside Chile. To some U.S. officials, the murder was only part of the problem; almost as appalling was the gall Chile had shown in trampling on U.S. sovereignty. When Secretary of State George Shultz learned in 1987 that the CIA now considered Pinochet to have worked to cover up the crime, he reported to Ronald Reagan that “this is a blatant example of a chief of state’s direct involvement in an act of state terrorism, one that is particularly disturbing both because it occurred in our capital and since his government is generally considered to be friendly.”

It wasn’t until Chileans — along with much of the rest of Latin America — began their transition from dictatorship to democracy that justice finally started to become possible. In 1990, Patricio Aylwin, a leader of the 1988 “No” campaign against Pinochet’s continued rule who headed a broad coalition dominated by the center-left, ascended to the presidency. Soon after, the Chilean legislature agreed to cash compensation for the victims’ families. More controversially, the Letelier case was reactivated and Contreras and Espinoza were put on trial. Chileans avidly followed every decision and revelation during the trials — which were televised, a first in Chile. Many also wondered if their fledgling democracy would survive against a strong military that was still led by Pinochet. “I’m not going to any jail,” was Contreras’s vow. Or was it a threat?

Because the Letelier assassination took place outside of Chile, the case stood as a rare exception to a 1978 law that granted amnesty for Pinochet-era human rights abusers for crimes committed up to that year. Yet there was pressure from much of Chilean society, which believed that justice was critical to beginning to heal the wounds from the Pinochet era.

In 1995, finally, a Chilean Supreme Court ruling sent Contreras and Espinoza to prison for seven and six years, respectively.

The decision paved the way for a partial — although incomplete — accounting for the crimes of the Pinochet-era in the years that followed. Over time, Chilean courts would adjudicate more than 1,000 cases of human rights violations.

Today, the curtain is finally falling on the Letelier affair. Contreras died in prison in 2015, having served out his Letelier sentence but also having earned 59 additional sentences totaling another half-millennium. A few months later, Secretary of State John Kerry declassified hundreds of documents, adding to others already made public by previous U.S. administrations. These files came as close as any ever would to confirming that Contreras had received the kill order directly from Pinochet. The general’s death in 2006 sealed his lips, but history is not done judging him.

The Letelier case is now in good company. From Argentina to Guatemala, brutal cold warriors, long coddled by impunity, are facing justice in many of Latin America’s courts.

The Letelier and Moffitt families, their allies, the investigators, and many diplomats should be praised for ensuring that some justice was done — and that the power of democracy and rule of law was shown for all in Latin America, and the world, to see.

—

McPherson is Professor of International and Area Studies, ConocoPhillips Chair in Latin American Studies, and Director of the Center for the Americas at the University of Oklahoma. He is the author or editor of nine books, including The Invaded: How Latin Americans and their Allies Fought and Ended U.S. Occupations.