This article is adapted from AQ’s print issue on how to make Latin American cities better. Click here to see the rest of our Top 5.| Leer en español

CALI, Colombia – Poblado 2, a rundown neighborhood deep in one of Cali’s roughest eastern districts, is no longer the urban war zone that Jhony Fernando Fernández remembers. A group of early teens kick a soccer ball around a dusty pitch overlooking a canal while an elderly man hauling a cart loaded with discarded cardboard and plastic bottles ambles by. A fruit seller who has jerry-rigged his stall to a chuntering motorbike parks up on a corner to sell pineapples, papayas and mangos. A convivial hustle.

“Two years ago you could be shot walking around here,” said Fernández, 33, who has a scar on his calf to prove it. “That was when life wasn’t worth more than the price of a bullet.”

Fernández, like Poblado 2, has undergone a transformation. Just two years ago he was a member of one of the warring local gangs, or pandillas, that controlled tiny territories of just a few blocks. He would make money to feed his four children by snatching the phones of passersby and selling them, while his friends peddled cocaine and marijuana. Crossing invisible borders, from one block to the next, could be a death sentence.

Fernández’s evolution mirrors Cali’s rebirth

Fernández’s evolution mirrors Cali’s rebirth

The infamous cartel that once dominated Cali, the sprawling capital of Colombia’s southwestern Valle de Cauca province, was dismantled in the 1990s. But its homicide rate remains the 21st-highest in the world, according to the Citizen Council for Public Security and Criminal Justice. Smaller cartels and gangs known as oficinas continue to rule many neighborhoods, relying on vulnerable teenagers who face more lenient justice than adults if caught — and are easily sucked in by the material allure of cell phones and motorcycles the drug-dealing life can provide.

That was the reality chewing up Fernández.

“We all knew then that this life was going to end in jail or the morgue, so we didn’t care how we got there,” Fernández said in a lilting deadpan, sitting near a canal that was once a gang lookout spot. “But now I never want to die.”

More: Cali’s Mayor on How to Build More Harmonious Cities

The turning point for Fernández and his contemporaries came two years ago. While sitting on a bench, he glanced in a cannabis-induced haze across the canal at a nearby elementary school. He saw a teacher tending to a small garden.

“That was my eureka moment,” he said with a smile. He walked over and introduced himself to the educator. “That’s when I found something else.”

The school’s principal, Hugo Alberto Lozano, cut a deal with Fernández and his fellow gang members: As long as violence decreased, the school would help out with locals’ hobbies. Today, the school gives night classes in computer science, music and design, and plans to roll out courses in carpentry and mechanics.

Around the same time, Cali’s city government was rolling out an outreach program in troubled neighborhoods like Poblado 2, dubbed Territories of Inclusion and Opportunities (or TIOS, which in Spanish means “uncles”). TIOS, with public and private investment, saw city representatives give music and leadership classes to Fernández and his friends — some of whom were barely literate. A local bank set up a microfinancing initiative that funds social projects, including an upcycling brick business. A number of public-sector jobs were also set aside for neighborhood residents. Fernández, who had by then developed a passion for horticulture, found work with the city’s environmental agency. He now travels to protected wetlands on the fringes of the city to monitor bird migration patterns and guide tourists.

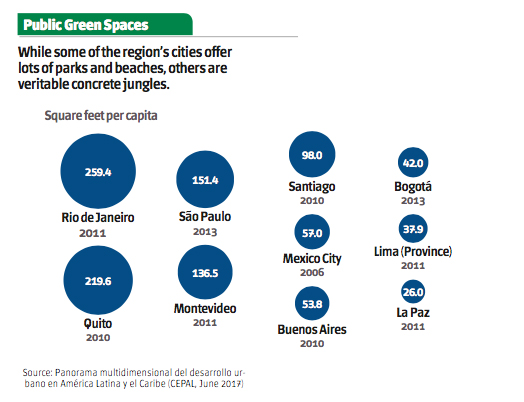

More: The Importance of Green Urban Spaces

However, nothing would have been possible without peace among the warring gangs.

Poblado 2 was divided into informal territories. Fernández lived in Siri, just one block from El Puesto, but crossing that invisible border could trigger a hail of bullets. He decided to broker peace with Yoranys Marulanda, the leader next door, through backchannels and diplomacy. “One time, someone from El Puesto wanted to throw a party but had no balloons. I had some left over, so I let them have them,” Fernández said. “It was hard (to make peace), and there was resistance, but the violence stopped. … Maybe Colombia could learn something from us.”

Today, Fernández walked along the unpaved streets that once marked the border between two territories. He stopped to greet Marulanda, once a sworn enemy, and they looked like lifelong friends. “Peace is a paradise,” Marulanda said, grinning infectiously. “I wouldn’t trade it for anything.”

Every Halloween, Fernández organizes a group walk for members of Poblado 2, whatever their history, around edges of the neighborhood that were off limits before. Rita Campaz, a neighborhood resident, said that before she would be scared to let her kids out the house, let alone go trick-or-treating in enemy territory. She thanked Fernández for making that a possibility.

But despite the bonhomie, problems persist. Unemployment is still high and the TIOS program could be axed when Cali’s next mayor takes office in 2019. Lina Buchely, a professor in political science at ICESI, a nearby private university, argues that programs like those in Poblado 2 are limited. “Classism in Cali is rife, and so you can give them a job, but when that contract ends they will struggle to get another one, as no one wants to hire someone from a rough neighborhood,” the academic said. “They pass like a hot potato from one thing to another.”

Fernández, too, worries about the future. His contract with the environmental agency ends in October and without anything lined up after, he is not sure what he will do. “Crime is behind me, of course, I love this life too much,” he said, taking shade from the beating sun. “But unless I find work at the end of the year, I don’t know what I will do.”

—

Parkin Daniels is a freelance journalist based in Bogotá