This article is adapted from AQ’s latest issue on reducing homicide in Latin America.

For almost two decades, countries in Latin America and the Caribbean have searched for that elusive form of trade integration that would unleash the full potential of their nearly 600 million people in a $5 trillion market.

To be fair, a lot of work has been done. The region has 33 preferential trade agreements (PTAs), more than any other in the world. If signing the most trade pacts were a sport, Latin America and the Caribbean would be the hands-down winner.

On the positive side, these pacts have increased trade in dollar terms within the region by an estimated 64 percent on average since the early 1990s.

But this complicated trade architecture has two problems. First, these pacts have a huge missing link: The two largest economies in South America — Argentina and Brazil — are linked to each other but not to Mexico. Those three economies together account for almost two-thirds of the gross domestic product of Latin America and the Caribbean, but the three nations contribute just 7 percent to intraregional trade. In addition, the three main subregions (Central America, South America and the Caribbean) are barely linked to one another.

The second problem is that this mosaic of 33 relatively small pacts has spawned accompanying rules of origin agreements. These are designed to ensure that third-party producers don’t exploit the PTA by setting up maquiladoras that re-export goods with just a few local add-ons.

The result is a complex web of 47 rules of origin agreements. Complying with these agreements can give headaches to even the most sophisticated exporters, let alone the region’s numerous small and mid-size firms. Firms are hard-pressed to acquire goods from the most efficient producers and struggle, in turn, to join competitive regional supply chains. We have calculated the cost of these rules of origin pacts to be the equivalent of an import tariff of 15 percent.

More trade agreements do not translate into better integration.

A Better Path

So, Latin America and the Caribbean cannot afford to rest on its laurels. We need to fill the integration gaps, particularly among the largest economies, and promote convergence among the pacts. This is a strategy that would eventually lead to a Latin American and Caribbean Free Trade Agreement (LAC-FTA).

This is the logical thing to do anyway, but even more so in the face of a protectionist backlash in some developed countries and the rise of mega-trade pacts elsewhere that are starting to dominate the international scene. Think of the recently signed Comprehensive Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership, the China-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, or the talks to establish an African Continental Free Trade Area.

Being a small PTA in Latin America is a perilous position, given that even a full-fledged LAC-FTA would be just half the size of the Chinese market, one-third the size of the EU’s without the U.K., and one-fifth the size of NAFTA.

There are different ways to pursue a LAC-FTA. Leaders can pick the strategy best suited to their political circumstances and ambition. They can take a more cautious, step-by-step approach. They would first harmonize rules of origin among existing pacts and then fill the relationship gaps. This hands-off solution would require less political capital, but the incentives are less obvious, particularly for those missing links involving smaller economies. For instance, the incentives for expanding the network of agreements between Central America and the Caribbean, given the limited size of their markets, will be significantly lower if the initiative does not become part of a coordinated effort to create a regional market.

Alternatively, countries could plot a nonstop course to a LAC-FTA. A critical mass of countries, with enough economic gravitas, could get negotiations going. Here Mexico, alongside Brazil and Argentina, can play a critical role.

These three countries are already partially linked by a 2002 legal and normative framework for bilateral trade negotiations between Mexico and each of the Mercosur members. Within this framework, Mexico has signed bilateral agreements with Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay. All four countries also signed a separate agreement for vehicles and auto parts. Of these, only the one between Mexico and Uruguay went on to become a full trade agreement, under the World Trade Organization’s definition. Mexico’s agreement with Brazil covers only 14 percent of tradable products, of which only 45 percent were granted duty-free status. The agreement with Argentina is somewhat more comprehensive but does not go beyond 30 percent of tradable goods. The auto agreements are also far from comprehensive, with quotas for duty-free goods.

As the recent trade negotiations in North America have made clear, Mexico has never had a greater incentive to look for alternatives. What is at stake is a valuable opportunity to become less dependent on the U.S. economy. An emerging pro-trade consensus in both Brazil and Argentina suggests that, despite past tribulations, this time the partnership can prosper. A commitment by Brazil and Argentina to initiate a process of unilateral liberalization alongside their preferential initiatives could help convince Mexico that this time things will be different and that they are now fully committed to integration.

Also, complex architectures like a customs union with supranational institutions should be avoided. Instead, the objective should be a plain vanilla free trade zone, with a focus on goods and services as a first step. Other chapters on intellectual property, labor or the environment, which have become popular in some PTAs, should not be ruled out, but they are not initially the main goal. As shown by the Pacific Alliance, these areas may be considered after the foundations for a regional free trade area for goods and services is firmly in place. Likewise, the institutional architecture should be intergovernmental rather than supranational in nature, with a commission made up of ministers or senior-level officials overseeing the implementation and operation of the agreement and guiding its future evolution.

The first step for this type of initiative would be for the interested parties to call for a summit of heads of state and presidents, whose main objective would be to outline the goals, mechanisms and timetable for the negotiation process. There would be no need for all the region’s governments to be involved during these early stages. All that would be required is a critical mass of countries with enough gravitational pull to get the momentum going.

Negotiations toward the agreement should follow similar guidelines to those discussed for the intermediate stops on the route to the full LAC-FTA: that is, guidelines that strive to strike the right balance between flexibility and meaningful results. The first guiding principle should be for the LAC-FTA to be a living agreement, one whose text should allow for the addition of new members and new issues. It should create conditions for negotiations to move ahead with a hard core of participants and issues, without precluding the possibility of future expansion in both these areas when political and economic conditions allow. There should be incentives for early birds though, since size matters for the agreement’s success. Latecomers would have to accept the original rules as given, except when issues are incorporated after their accession.

LAC-FTA’s $11 Billion Payoff

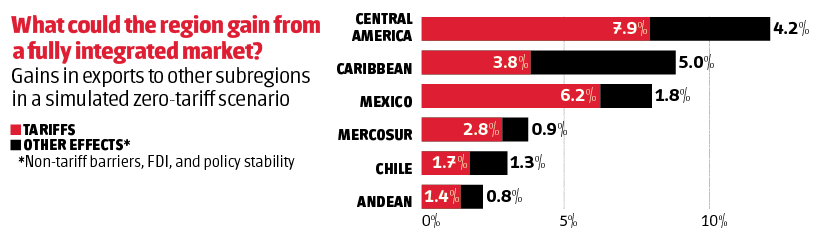

In our latest IDB report on trade and integration, Connecting the Dots: A Road Map for a Better Integration of Latin America and the Caribbean, we translated these arguments into numbers. Our lower estimates suggest that a LAC-FTA would produce an average gain of 9 percent in trade within Latin America and the Caribbean in inputs used in exports, bolstering the region’s underdeveloped value chains. The agreement would also boost intraregional trade in all goods by an average 3.5 percent or an additional $11.3 billion per year. Mexico is expected to be among the top winners, with its intraregional exports expanding by 8 percent, driven mostly by manufacturing goods.

These are relatively easy gains that neither Mexico nor the region should ignore, particularly in the current turbulent trade environment.

While the geopolitics of trade have become more complex in recent months, there is a risk that countries may not feel the urgency of moving on a LAC-FTA. After all, a strong global economy helped boost the value of Latin American and Caribbean exports 10.6 percent in the first quarter of 2018 against the same period last year, mainly due to higher demand from its major trading partners, particularly from other countries within the region and from the European Union. However, even here there are warning signs. Growth was slower than the 11.9 percent registered at the end of 2017 as prices of commodities such as coffee, soybeans, sugar and iron ore either dropped or flattened. We now have an opportunity to strengthen the economic backbone that helps us move beyond commodities and into a long-professed political aspiration for regional integration.

—

Estevadeordal is the Manager of the Integration and Trade Sector at the Inter-American Development Bank.

Mesquita Moreira is Principal Economist and Research Coordinator of the Integration and Trade Sector of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and Ph.D. in Economics from the University College London.