LIMA — Guillermo Rasquin likes to illustrate the story behind his migration from his native Venezuela to Peru with numbers: when he bought his house in San Bernardino, a residential neighborhood in Caracas, in 2014 he paid 700,000 bolívares for it. When that home’s air-conditioning unit broke down two years later, ballooning inflation meant the repair cost 780,000 bolívares.

The deteriorating economic and political conditions under President Nicolás Maduro made life, and business, difficult; they also pushed Rasquin, a former lawyer, and some 30,000 Venezuelans to settle in Peru over the past two years. Many migrants have come with few resources and settled in makeshift shelters, or are selling homemade arepas on the streets, but Rasquin is part of a growing cadre of middle-class professionals who have found in Peru both a refuge and a place to reinvent their careers.

Formerly a public servant for Venezuela’s Supreme Court, Rasquin moved to Lima in 2016 and capitalized on the country’s real estate and construction boom. He now owns a property management company in Lima. “You can have a Plan A and life makes sure you end up with Plan Z,” Rasquin told AQ from his spacious, bare bones office in Lima’s up-scale Miraflores neighborhood.

He isn’t the only one to benefit from Peru’s economic success. Structural reforms, fiscal discipline, rising commodity prices and an export-oriented mining sector have made Peru one of South America’s top performers over the last decade. The IMF projects 4 percent growth this year; the poverty rate is now less than half of what it was in 2005. A growing middle class has brought new consumers – and new opportunities for Venezuelan entrepreneurs with dwindling economic prospects at home.

“Peru has the conditions for new ventures,” said Nidal Barake, a Venezuelan who co-founded a mobile payments company and travels often to their branch in Lima for business. “Venezuelan capital has found a very fertile environment here.”

Peru’s open policy toward migration has also helped. In 2017, the government of Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, himself a descendant of immigrants, created the Permiso Temporal de Permanencia (PTP), a temporary residency permit that allows Venezuelans and others to look for jobs, apply for a tax number and receive some health and education services. Last year more than 26,000 Venezuelans applied for the program, and about 25,500 were accepted. So far, however, fewer than 500 of those have since sought work visas. On Jan. 30, the government rolled out a new residency category for Venezuelans whose PTP is about to expire and who have no police, criminal or judicial records. There are an additional 80,000 Venezuelans in Peru with tourist visas who could apply for the PTP, according to officials.

The policy has been particularly attractive for migrants looking for economic opportunities but also for the legal status that is hard to acquire elsewhere, as other countries in the region increasingly tighten restrictions on Venezuelans. In Panama, President Juan Carlos Varela introduced a mandatory visa for Venezuelans in 2017, saying the situation in that country “puts our security, our economy and the sources of employment for Panamanians at risk”. This year, the Colombian government stopped issuing border permits to Venezuelans, created a special taskforce to curb Venezuelan entry, deployed armed forces to the border and established daily entrance quotas. Brazil has also enforced tighter border controls and militarized some of the most popular entry points. Ecuador, a transit country for migrants on their way south, offers visas under UNASUR agreements but they cost between $200 and $500, a stark contrast to the $13 a migrant in Peru must pay for the PTP.

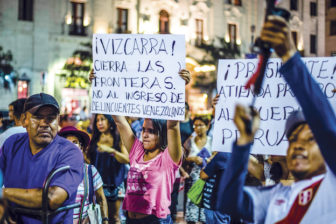

That’s not to say starting a new life in Peru is without obstacles. Some local officials and journalists have reacted negatively to influx of immigrants. Local news coverage about the growing Venezuelan community focuses mostly on arepa vendors and other street hawkers, highlighting alleged tensions with local labor. Earlier this month, two congressmen voiced their concern about Venezuelans joining the labor market and called for tighter immigration controls.

Cultural differences also cause misunderstandings. Ana Naranjo, a statistician, worked for a leading Venezuelan payroll firm for 20 years. In 2017, she became the firm’s first and only foreign-based employee, working from Lima and studying the market for opportunities. She said that the Andean business climate can be conservative compared to Venezuela’s Caribbean exuberance; she often asks her sister, an accountant who moved to Lima three years ago, for help recognizing the nuances of Peruvian business protocol.

In general, though, Peruvians tend to embrace international visitors and immigrants, an attitude likely enhanced by the country’s own recovery after a period of internal conflict and hyperinflation. Peru has a diaspora of over 2.5 million, and during Venezuela’s oil boom thousands of Peruvian technicians and professionals moved to Caracas and settled there, raising dual-citizenship families. These young men and women were among the first to make the way back to their parents’ country of origin.

Venezuelans, for their part, are doing what they can to integrate into Peruvian society. A social media campaign called #noalaxenofobia (no to xenophobia) has sprung up to combat negative stereotypes about Venezuelans in the country. It features Venezuelan professionals from actors to hair stylists describing how they contribute to their adopted country.

Still, like members of the Venezuelan diaspora everywhere, many in Peru keep reminders of their home country close by. Naranjo arrived to our interview wearing a shirt with “Caracas por siempre” stamped on the front. Rasquin wore a discreet but colorful bracelet with the red, yellow and blue of Venezuela’s flag.

“We detect each other,” Rasquin said. “Most of the days I try to wear something from my country. It makes me feel safe.”

Such solidarity can give Venezuelans abroad a sense of belonging, wherever they are. On a recent afternoon, Naranjo was walking in Lima with her son when suddenly she saw a familiar face getting off the bus: “Miss Vivi! How could it be?” It was her son’s favorite English teacher from back home in Caracas. The woman had moved to Lima with her family and was now in-between jobs, sending resumés to schools before the start of the new school year.

—

Cantú is a journalist and a professor of politics and international relations at Universidad ESAN. She lives in Lima.